By Michelle Z. Donahue

If you’ve seen the movie Jurassic Park, you know that amber played a significant role in rebuilding a lost world: A mosquito trapped within its glossy resinous interior provided the genetic material for the film’s scene-stealing dinosaurs.

Now, by examining an 800-year-old piece of resin or tree sap, a Smithsonian scientist is helping reconstruct not fantasy dinosaurs, but actual ancient sea trading routes and human uses of plants in Song-dynasty China and by early kingdoms of Southeast Asia.

Analysis of resins found at the site of a Java Sea shipwreck from the 12th or 13th centuries indicates they may have originally been collected from plants growing in India or Japan. Though the ship carrying the resins may have never visited those regions, merchants on board could have acquired resins from those areas on separate journeys, providing evidence of early episodes of long-distance trade. Resins of this type were most frequently used as sealants for caulking ships. (Courtesy The Field Museum / Pacific Sea Resources)

Ambers, fossilized resinous tree sap, and resins, the non-fossilized variety, have long been a subject of study and fascination for Jorge Santiago-Blay, a research associate in the Department of Paleobiology at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. He recently collaborated on a study focusing on an unknown type of resin recovered from the Java Sea Wreck, a ship that sank in a remote stretch of water between Sumatra and Java during the 12th or 13th centuries.

The Wreck also carried great quantities of ceramics, and is thought to have been journeying from port to port to sell, trade and buy trade items throughout China and Southeast Asia. The recovered cargo, some 7,500 artifacts, is housed today at The Field Museum in Chicago.

This scale recreation of the Java Sea Wreck demonstrates what the ship carrying 230 tons of cargo may have looked like before it sank in the 12th or 13th century in the Java Sea. Just over 30 yards long and carrying 200 tons of iron, 100,000 pieces of Chinese ceramics, and a handful of chunks of aromatic resins, researchers believe overloading and turbulent seas may have contributed to its demise. (Photo Courtesy The Field Museum/Photo by John Weinstein; model by Nicholas Burningham)

A resin’s source

Santiago-Blay worked with Lisa Niziolek, a research scientist in Asian anthropology, and other colleagues at The Field Museum, and Joseph Lambert, a renowned organic chemist at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas. They and others pooled their expertise to try and determine the resin’s source plant.

“Knowing the species of plant the resin is from helps us determine where the material may or may not have come from,” Niziolek says. “Using this information, we can reconstruct ancient trade networks and social relationships [in the region]. We can also begin to think about how human activities affect the environment and other species.”

The Arkansas amber collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. University of Ohio paleontologist Royal Mapes collected and donated these specimens to the Smithsonian, which Jorge Santiago-Blay and numerous volunteers embedded in clear artificial resin. Embedding enables the otherwise brittle amber to be sliced into thin cross-sections for examination. (Photo by Michelle Donahue)

One of Santiago-Blay’s motivations for studying resins and ambers, also called exudates, is because these remnants of vanished worlds are vital clues in understanding the species composition and distribution of forests of the distant past.

“With ambers, I can close my eyes and imagine, millions of years ago, the huge forests in what is now Southeast Asia made of plants from this family,” he says. “They can also transport people to just a couple of hundred of years ago and show them how important biodiversity was even then.”

Spectroscopic imaging

Lambert is an expert in nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of resins and ambers, a technique that produces distinct line graphs for each resin species analyzed. To determine the identities of mystery samples like those from the Java Sea Wreck, he uses as a reference a catalog he has been assembling for 20 years of spectroscopic signatures from resins all over the world. Many of its signatures are from samples obtained by Santiago-Blay in his constant hunt for plant exudates from arboreta, forests and museums worldwide. The catalog now contains spectra “fingerprints” from approximately 2,000 specimens across 1,000 species of plants.

“The general idea is that I get the samples, and Joe generates the spectrum,” Santiago-Blay says. “When we have an unknown sample, we analyze it and compare the output with known samples to make the botanical association.”

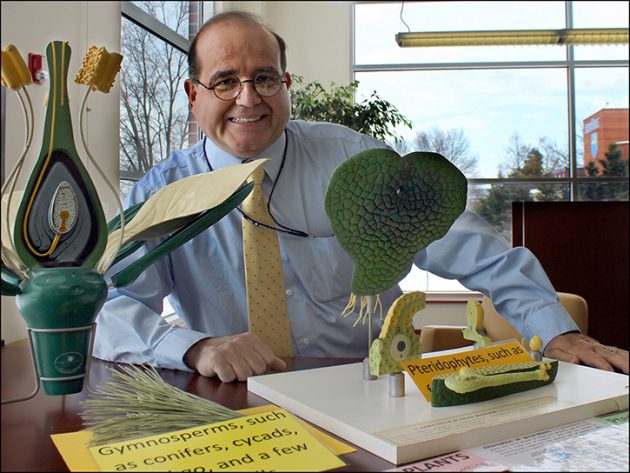

Jorge Santiago-Blay holds a piece of amber from the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. (Photo by Michelle Donahue)

Resin from the Java Sea Wreck remains a mystery, however. Although the scientists couldn’t identify its exact tree species, they did narrow it down to the tree family Dipterocarpaceae, a group containing nearly 700 species. One member is Shorea robusta, a valued hardwood widespread throughout Southeast Asia.

With the assistance of Diane Wendt, associate curator of science and medicine at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Santiago-Blay went through the collection in that museum to add them to Lambert’s catalog. Among the specimens they examined was a modern Shorea sample. Its spectral signature looks extremely similar to the signature of the Java Sea Wreck sample, yet it is not a perfect match. After 800 years submerged in seawater, the shipwrecked resin seemed to have experienced artificial aging that make its signature look much older than it is.

Japan or India

Lambert said he initially believed the mystery resin’s signature pointed to an Indonesian origin, but further comparison suggested it may have come from as far away as Japan or India. “But those are far apart,” Lambert says. He and Santiago-Blay both agreed that there needs to be more analysis of samples from India and Japan, and the tree species from which the Java Sea Wreck resin originated needs to be narrowed down.

In Southeast Asia at the time of the Java Sea Wreck, resins and ambers would have been valuable trade items, just as they are today. Santiago-Blay and Lambert’s work is also helpful in identifying fakes and forgeries.

“Amber may command great sums of money because it may contain examples of organisms considered rare, such as amphibians, reptiles and scorpions,” Santiago-Blay says. “But buyer beware: there are unscrupulous sellers willing to make money from objects that are not genuine amber.”

In modern times resins have seen many new uses, from fillers in construction to coating the undersea transatlantic cable. They are still used to create traditional medicines in China, and incense, perfumes, and lacquers in other parts of the world. In ancient times, resins had medicinal and ritual uses, and served as a tribute to the Chinese imperial court.

In the end, locating where a resin’s origin not only tells researchers which plants were considered valuable, but also suggests something about encounters between people in the various places the resin was traded.

“What was it doing here? What were the ports it went to? Was its end use to be for caulking in a shipyard, or burned as incense at a religious site?” Lambert says. “Getting answers to these questions is how archaeologists spend their time, and what scientists are able to provide a bit of help on.”