By Michelle Z. Donahue

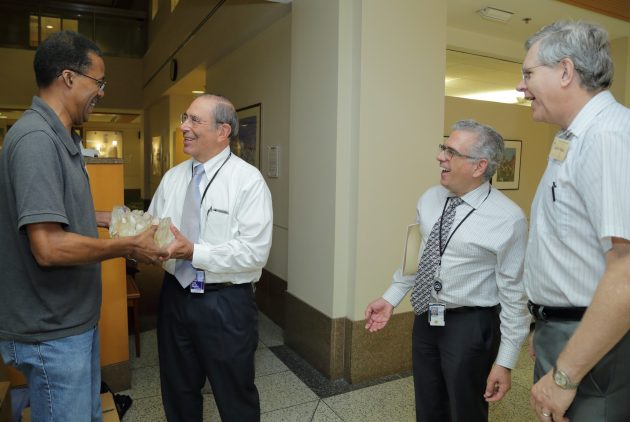

Smithsonian mineralogist Mike Wise hands NIH Clinical Center director John Gallin a large specimen of quartz at the opening of the “Minerals in Medicine” exhibit at NIH. Frederick Ognibene, clinical center deputy director for educational affairs and strategic partnerships and director, NIH Office of Clinical Research Training and Medical Education and Jeff Post, look on. (Photo: NIH Clinical Center)

Have an upset stomach? Pop a chalky, chewable antacid. Maybe you’ve got a painful cut or burn. No problem; reach for a healing ointment or cream. Or maybe you broke your arm as a kid. If so, you probably sported an itchy plaster cast.

What all of these remedies and countermeasures share is as common as the earth beneath your feet: minerals. Calcite, silver and gypsum are key components of those treatments, and hundreds of other minerals are found in medical therapies and applications in hospitals, clinics and medicine cabinets around the world.

It was this idea that sparked “Minerals in Medicine,” a new exhibit at the National Institutes of Health headquarters in Bethesda, Md., on loan from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History Gem and Mineral Collection. Conceived by Dr. John Gallin, director of NIH’s Clinical Center, and Smithsonian geologists Jeff Post and Mike Wise, the goal of the 18-month exhibit is not only to educate, but also to share a bit of the wonder and beauty of minerals with an audience who might be tiring of their tenure at the hospital.

Smithsonian mineralogist Jeff Post, right, and NIH Clinical Center director John Gallin officially open the “Minerals in Medicine” exhibit at the NIH Clinical Center. (Andrew Propp photo).

About 40,000 patients are under care at NIH at any given time; nearly all are there as a medical measure of last resort. The rare, often grave nature of their conditions and treatments are grueling on many levels.

The exhibit is located in the main registration area of the hospital, flanking either side of a long saltwater aquarium occupied by brilliant tropical fish. The wide corridor where the mineral exhibit sits is exceptionally busy, with patients and staff constantly rushing by. But every few moments, one, two or a handful of people slow down to gaze at the strange symmetries, colors and forms of the medical minerals there.

“One of the unique things about this hospital is we have a lot of patients who spend a lot of time here. We have children who might be here for a year,” Gallin says. “If you’re in a regular hospital, you stay in your room. Here you don’t stay in your room. So if they can stumble on this, and stop and look and smile, that’s what we had hoped for.”

Flourapatite with calcite specimen in the “Minerals in Medicine” exhibit at NIH. (Andrew Propp photo)

“It’s a somber, intense place, and people are there because it’s one of the most difficult times in their lives,” Post agreed. “It was our hope that we could transfer a little energy from [the Smithsonian] and put a little smile on people’s faces.”

Featuring 39 minerals from azurite to zinnwaldite, the specimens are not only beautiful to behold, but all have played an important role in some aspect of human medicine.

“Most people never equate the uses of minerals to anything in their daily lives,” Wise notes. “But minerals really are nothing more than chemical compounds.”

Shock-blue azurite, for instance, has been a source of copper since ancient times. There’s a goldilocks zone for copper inside the body; too much or too little can cause serious damage. Outside the body, copper is a potent antimicrobial agent, used in everything from bedrails to topical antiseptics. It’s also found in malachite, a deep green mineral often used in jewelry.

The eight specimens of calcite on display at NIH, each vastly different from the next, are just a hint at its importance for many different applications: its main component is calcium, one of the most abundant minerals on earth, and in the human body. Necessary for healthy bones and teeth, calcium from calcites have been used in everything from antacids to manufacturing high-precision optics for scopes used in medical research.

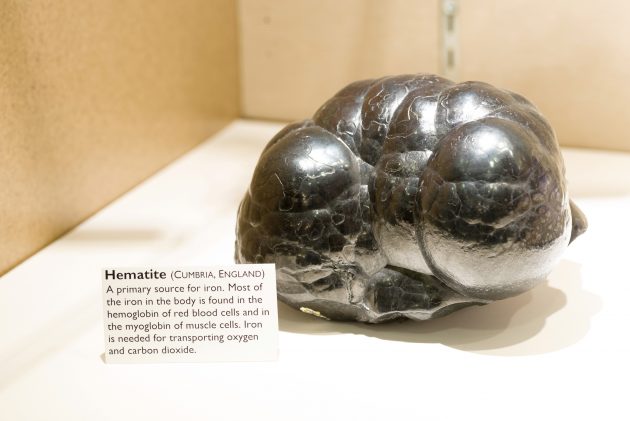

Hematite specimen in the “Minerals in Medicine” exhibit at NIH. (Andrew Propp photo)

There’s even a sample in the display that came from just down the road from the NIH: a small chunk of gold from Montgomery County, Md.

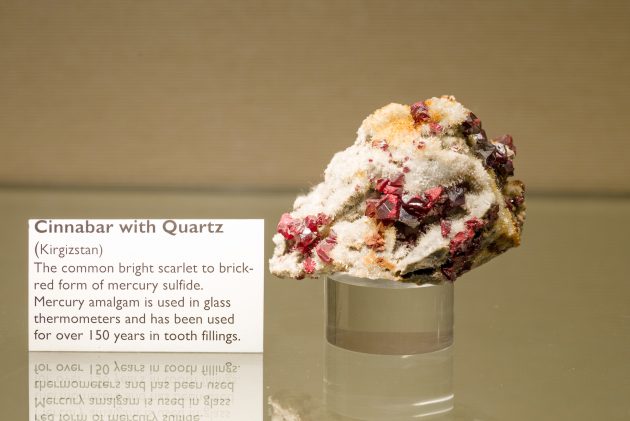

Gallin, a rockhound from the age of five after he found a garnet crystal lying amid a gravel gas station parking lot during a family road trip, worked with Wise and Post to winnow down selections for the exhibit. He solicited input from clinicians and researchers around the NIH. Suggestions trickled in: platinum, silica, titanium, talc, bismuth, mercury. Arsenic came quickly to Gallin’s mind, as it was a key component to the first modern antibiotic derived by 1908 Nobel Prize recipient Paul Ehrlich. Wise and Post then included a specimen of realgar, an important (but non-toxic) source of arsenic.

With more than 375,000 objects in the Natural History Museum’s Gem and Mineral Collection, it’s rare that more than just a fraction of the pieces in the Smithsonian’s care are ever removed from the long, dim aisles where they reside. Hunting through the collection gave Post and Wise an opportunity to look at the collection with new eyes, especially among the largest pieces where they perch on tall, deep shelves in one corner of a cavernous storage area.

“These have been sitting here for so long and don’t get used much, so it’s been a good opportunity for us to get some use out of them,” Wise said.

Cinnabar with quartz specimen in the “Minerals in Medicine” exhibit at NIH. (Andrew Propp photo)

Unfortunately for the realgar sample, it was quickly returned to darkness: Post and Wise belatedly realized that as a photosensitive mineral, the bright lights of the NIH hospital display case had caused it to start disintegrating as it altered into the related mineral orpiment.

“We got a real kick out of this,” Post said. “Many of the specimens at NIH have never been on display before. We cleaned them up and they get their moment on the stage, and wow, they look nice! It gave us a chance to appreciate them better. Look at them! How can you not love them?”

The two mineralogists admit they sometimes become immune to the spectacular nature of the materials they work with, and forget how transformative just looking at them can be for people who don’t see them on a daily basis.

“Our entire goal is to help people think about the earth a little differently, and you can’t be so jaded about the place you live when you realize the earth made these things,” Post said. “They exemplify the complexity, beauty and brilliance of the earth, and for many of us here, it was the first time seeing something like this that put us down the path, like magic, wanting to know more.”