By Michelle Z. Donahue

Master stone carver Bernat Vidal chisels a piece of Seneca sandstone during the 2016 Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, D.C. Vidal is making a rough replica of a corbel from the Smithsonian Castle. (Photo by Michelle Z. Donahue)

Peering closely at the surface of the ruddy red Maryland sandstone block, Bernat Vidal sets a chisel resolutely against the stone and confidently taps it with a wood-handled mallet. With every strike, puffs of dust wisp upward, and tiny sharp chips fly off in all directions.

Vidal, unflinching, etches the beginnings of an incised line into a semi-circle that he has already coaxed out of the squared-off stone. With the easy reflex of 30 years’ practice, he flicks away larger shards to reveal the beginnings of an ornate corbel to decorate a stone arch.

The arch in question is on the west face of the Smithsonian’s iconic red sandstone Castle, and the sculptor bending to the task traveled from the Basque Country, located in northern Spain and southern France, to share his craft with the public at the 2016 Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The unique Seneca Creek sandstone block from a nearby quarry is very similar to the buttery sandstone Vidal chisels in his studio outside Bilbao, on Spain’s northern coastline.

“We gave Mr. Vidal a couple of pieces of Seneca sandstone from our attic stock and a photograph of one of the Castle’s decorative corbels,” says Paul Westerberg, registrar for the Castle Collection. “He’s going to leave it unfinished and rough for us in order to show his tool marks in the stone.”

Vidal’s unfinished block will eventually go on display in the Castle’s Schermer Hall next to an 1846 Castle model by architect James Renwick “as a representative sample of how these carvings are made,” Westerberg adds. “People normally only see the finished product. It’s rare to see something in the process of its creation. We were very happy a master stone carver was working on the Mall.”

Though once renowned in the Middle Ages for their skill, today, only a handful of traditional Basque stone workers continue the craft. Originally a painter and ceramics artist, Vidal came to the tradition almost on a whim, but became so smitten that he began to teach to the younger generation at a stone carvers’ college in Bilbao 20 years ago.

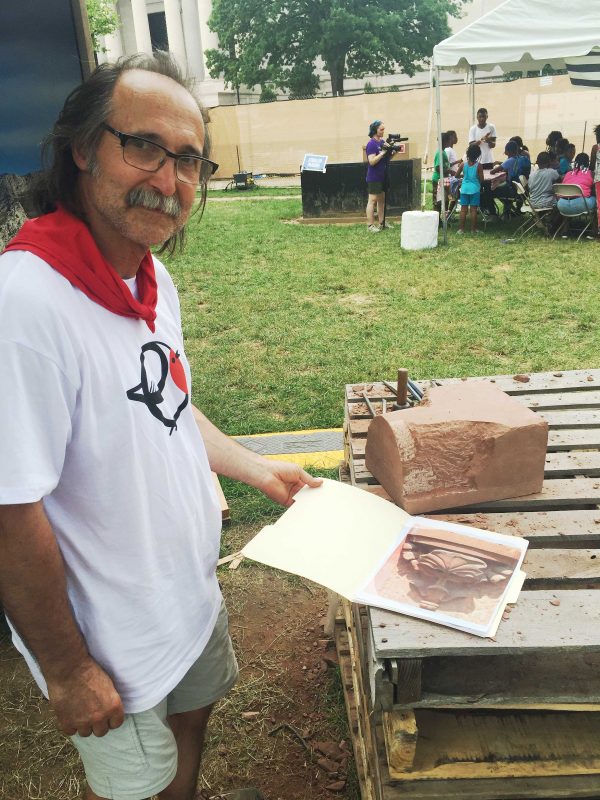

Master stone carver Bernat Vidal displays a photograph of a corbel from the Smithsonian Castle that he is using to create a replica from a piece of Seneca sandstone. Vidal was working on the National Mall as a participant in the 2016 Smithsonian Folklife Festival. His corbel will eventually go on display in the Castle’s Schermer Hall. (Photo by Michelle Z. Donahue)

Among his works: a 1.5-ton coat of arms, carved from a 6-ton block, mounted on the City Hall of Guernica, an important symbol of Basque autonomy before and after it was bombed during World War 2; and the Puerta del Mar in the Dominican Republic, commissioned in 1992 for the 500th anniversary of the discovery of the Americas.

Vidal laments the economic realities that make even highly regarded traditional craft a lackluster prospect for Basque youth, though he hopes that his efforts in educating others and demonstrating the craft may yet bring renewed interest to the trade.

Insider writer Michelle Donahue spoke to Vidal during a lull at the Festival, and he shared some of his thoughts on the history and future of Basque traditional stone carving.

Q: Can you talk a little bit about the importance of what you do as a reflection of the Basque culture as a whole?

Vidal: Basque carvers were very important during the Crown of Castile [the consolidation of Spanish kingdoms in the 13th century]. These were carvers whose works were very much sought after, but then this art was all forgotten because all of this work was being done outside of Basque country. So, the Basque people as well as the rest of Spain have lost the tradition. For me to discover this art form was very beautiful.

Q: Was the purpose of traditional Basque stone carving originally for house building, fortress building, or some other reason?

Vidal: Historically, it was for house building and making artistic works. It was even further divided than that, with specialists in different forms. Nowadays, 80 percent is for custom work at houses, family crests, or the name of the house in stone with different designs, because in Spain traditional homes have names.

Q: How did you come to be a stone carver? Was this a family tradition?

Vidal: In the village where I lived, there was strong stone influence—not in carving, but in quarrying. Then I had the opportunity to take a carving class and I loved it, the complexity of the rock. It was something that filled me.

Q: Was it easy for you to master?

Vidal: It wasn’t too easy, but it wasn’t too difficult, either. When you are absolutely dedicated to something, you slowly begin to master it.

Q: Has your work attracted the interest of young people who want to learn from you?

Vidal: Approximately 20 years ago, I was a professor at the stone carvers college in Bilbao. But now with the economic crisis in Spain, few are interested. It’s a tough and dirty job, and people nowadays prefer to be in front of a computer.

A corbel is the terminus or end of a projecting decorative arch, Paul Westerberg says. A number of corbels similar to that being carved by Bernat Vidal can be seen in this photo of the Smithsonian Castle’s north face. (Flickr photo by PhotosbyTamir)

Q:What do you hope people here learn from your work?

Vidal: By virtue of seeing it here, people can value the effort that is required to do this kind of work, and that there are very few people who actually do this. Truthfully, I’ve been surprised—people have been very interested in all of the aspects of my work, with a desire to learn [about] my craft.

Q: How do you find the experience of carving the Castle stone compared to the others you’ve worked with?

Vidal: It’s intriguing. Where I’m from in Navarre there is also a different kind of red stone that looks exactly the same. But upon a closer look there are differences—that one has larger grains and it’s more abrasive, whereas this one is much finer and is very malleable, but breaks very easily.

A selection of the work of master stone carver Bernat Vidal, from the Basque Country in northern Spain and southern France. Vidal is in Washington, D.C. as part of the 2016 Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, D.C.

Q: How long will it take you to complete this piece?

Vidal: It’s difficult to say. It’s a very detail-oriented job. I’d calculate that if I was back in my shop, I’d say about a week.

Q: Will you take it back and finish it or will you stay here until it’s completed?

Vidal: I can always send it back because it would be great to show all of the phases of the work, so others can see what is necessary to prepare a stone for carving. But the Basques also like this type of stonework, so they might want to keep it! [laughs]