By Michelle Z. Donahue

Visitors learn how to assemble a BioCube at an event at Seneca Park Zoo in Rochester, New York. (Image courtesy Pamela Reed Sanchez, Seneca Park Zoo Society)

Profound ideas don’t need to be complicated. A simple cube made of aluminum tubing, a centerpiece of a new exhibit “Life in One Cubic Foot,” is revitalizing public appreciation for biodiversity and even rallying communities behind their local environments.

By placing these one-cubic-foot frames in different ecosystems then counting and classifying all the different living organisms that pass through them, Smithsonian invertebrate zoologist Chris Meyer and wildlife photographer David Liittschwager have launched a project that today is providing important environmental data, as well as dazzling visitors at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, in Washington, D.C. What’s more, its a concept that has grown legs and is starting to disperse across the country and the globe.

Known as “BioCubes,” the frames of slender 12-inch-long aluminum tubes are small enough to fit into a person’s lap. They are placed in a relatively undisturbed area that is typical of the habitat surrounding it. The diversity they have revealed in some seemingly desolate places is remarkable.

Smithsonian researchers Chris Meyer (right) and Sarah Tweedt (center) examine Genesee River samples along with photographer David Liittschwager in August 2015. (Image © David Liittschwager)

Last August, for example, Meyer and Liittschwager worked with the staff of the Seneca Park Zoo in Rochester, N.Y. to document biodiversity in the Genesee River, which is recovering from decades of industrial pollution. Still listed as an “area of concern” by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency the biocubes revealed the river is home to more life than anyone expected.

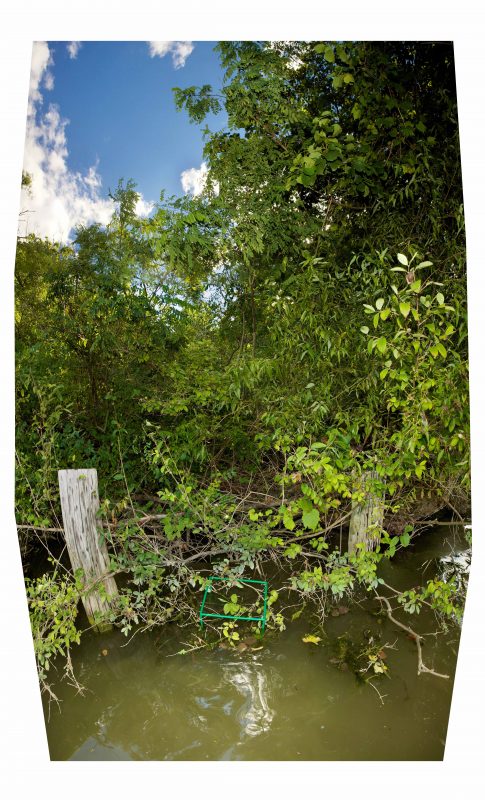

In the Genesee, a BioCube was placed in a spot half in, half out of the water, close to the bank but not directly on it, and transected by leafy, low-hanging branchlets. Liittschwager used GoPro cameras to record species that flew, walked, swam, slithered or waded through the cube. The team took water samples and netted flying species seen flitting through.

When the data and images were compiled, “People said things like, ‘Wow, I thought nothing lived in that river, and you found all that?’” Meyer says. “There’s a new story to tell, and its one that rallies the community. They’re all impacted by the greater appreciation for the everyday spaces around them.” In the United States biocubes also were set up in Central Park in New York City and on the California coast.

A selection of reef creatures from Mo’orea, French Polynesia revealed through inventorying one cubic foot from a reef off the coast of the Pacific island. (Image © David Liittschwager)

All the players

Director of the Mo’orea Biocode Project in French Polynesia, showcased as part of the “Life in One Cubic Foot” exhibit, Meyer worked to create the first complete catalog of non-microbial life in one of the world’s most diverse tropical ecosystems. To accomplish this, he gathered genetic samples for a process known as DNA barcoding, which is used to create a DNA library of species in a given area. By replicating these efforts to other places around the globe such as Rochester, a series of detailed vignettes have emerged resulting in spectacular pictures and revelations about what is actually living in environments worldwide.

“If you have a group of pictures and data that represent the diversity of life in a certain place and time, that sample becomes comparable to other events in different places and times,” Liittschwager says. “If someone else starts to do that too, then you have this really useful dataset that someone far smarter than I might be able to learn something from.”

“The concept is that you want to capture all the players in these micro-ecosystem,” Meyer says. “There’s feedback and competition and foraging, and all those things are represented in a functioning ecosystem over the course of a normal day. You start to realize that the interactional envelope of species is more fined-tuned than you think.”

David Liittschwager (left) and Chris Meyer survey the Genessee River for the BioCube project in August 2015. (Image courtesy Pamela Reed Sanchez, Seneca Park Zoo Society)

In the Genesee as in other places, anything observed that couldn’t be captured was noted, and a photo made using a representative animal from elsewhere. All plant life within the BioCube also was documented. After taking pictures of each species and taking a DNA tissue sample from those hard to identify, Meyer and Liittschwager released most of the creatures. The DNA was sequenced at the Smithsonian, and eventually, all the photos will be entered into iNaturalist, a crowdsourced species identification platform, and genetic information entered into an international DNA database.

Community support

The Genesee marked the first time that a zoo got behind the one cubic foot project, and the success of their leadership effort is a model for others to emulate. For the Genesee project, the Seneca Zoo drew nearly 30 community organizations, non-profits, private entities and government agencies together to support the project and get the greater community involved. Initially, people weren’t so sure they wanted a literal microscope on the river—what if it turned out that the river hadn’t begun to recover at all, and was truly a blighted place?

Children discuss David Liittschwager’s photos at an exhibit of Genesee River biodiversity at the Rochester Contemporary Art Center earlier this year. (Image courtesy Pamela Reed Sanchez, Seneca Park Zoo Society)

That wasn’t the case.

“Between the photos and the DNA barcode sequencing we just got back, we found that a really strong food web is out there,” said Pamela Reed Sanchez, executive director of the Seneca Park Zoo Society. In fact, the team documented 134 species that went through the cube on the Genesee, including 17 that are new to the Barcode of Life DNA database. Several of the government partners will be able to use some of the data towards getting the river removed from the EPA’s list. “It’s one thing to document photographs and make species identification by eyeballing things, but the sequencing backs you up and creates a permanent record.”

Tom Snyder, Seneca Park Zoo’s director of programming and conservation action, added that delisting isn’t the end of the story for the Genesee.

Nestled among branches and aquatic plants on Rochester’s Genesee River, the Seneca Park Zoo’s BioCube awaits visitors. (Image © David Liittschwager)

“The hard science helps bridge the gap between coming off the list and the care of the river after,” Snyder says. “When you extrapolate what you find in the sheer smallness of the cube and compare it to how large our world is, you can easily create that link between how important each footstep is and how important it is for all the diversity there.”

Next month, Meyer will accompany a Seneca Park Zoo team and a group of students to Madagascar’s Ranomafama National Park to replicate the BioCube effort there. They also plan to go to Borneo next year for a similar project.

“Even if people only have one day to participate, they are all impacted by a greater appreciation for the everyday spaces around them,” Meyer says.