By Maria Anderson

In the last century, science has led to developments in medical diagnosis, treatment and inventions that have changed the lives of thousands of people with disabilities. Technological advances and research fostered a deeper understanding of the human body, enabling inventors to create new devices and implants.

To mark the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act*, Smithsonian Science News talked with Katherine Ott about three technological inventions that have improved the quality of life for many with disabilities. Ott is a curator in the Division of Medicine and Science at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Artificial Skin

Invented by Ioannis V. Yannas, an MIT professor of polymer science and engineering, artificial skin is used as a wound dressing (to protect underlying tissue from further damage) and to create a scaffold for new cell growth after extensive injury.

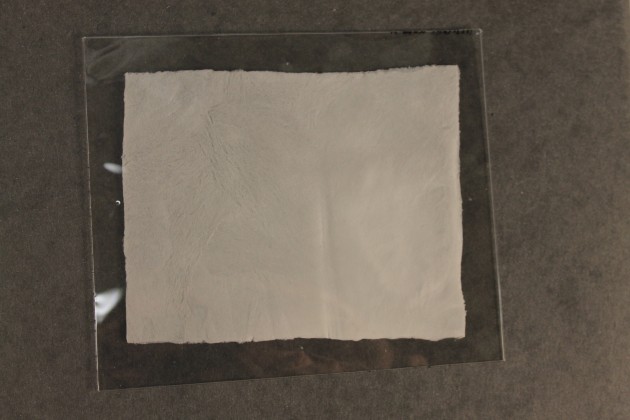

The first successful artificial skin, composed of biological materials, was approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration in 1998. (Artificial skin, 1997. Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History)

“For years, surgeons struggled to successfully graft skin from one part of the body to another, or even from animals (like pigs) to humans, thwarted by the body’s immune response and rejection of foreign skin,” Ott says.

“This led to tissue engineering in the 1980s, as a way to grow tissue using biomaterials to stimulate cells that then proliferate and differentiate into the kind of tissue needed, such as skin.”

In 1969, Yannas, who was inducted in the National Inventors Hall of Fame this year, was studying the physics of collagen and viscoelasticity in polymers when surgeon John F. Burke approached him about the problems of skin grafting. Yannas knew he needed to develop something that would keep bacteria out and moisture in, so he came up with a combination of materials: a synthetic layer of silicone that protects the skin from bacteria and seals in moisture, on top of a layer of tissue-like “scaffolding” that acts as a template where new skin cells can grow. Once the new cells build upon it, the artificial skin is absorbed by the body and disappears.

Artificial Limbs

Van Phillips designed the distinctive Flex-Foot appendage to use a person’s weight shift from leg to leg as a way to store and release energy. (Artificial lower limb with custom graphic socket, 2003.)

“A common motivator for invention and innovation is immediate physical need. In the history of disability, the best solutions often have arisen from the creative minds of the people with the most at stake,” Ott says. “That was certainly the case for Flex-Foot inventor, Van Phillips.”

After losing his left leg below the knee in a college waterskiing accident in 1976, Phillips found himself looking for a suitable prosthetic option that would allow him to run again. Frustrated with the prosthetic technology at the time, he switched his studies to prosthetics and began to research better ways to design a prosthetic foot with strength, flexibility and lightweight materials.

Studying the structure of a cheetah’s hind leg, Phillips came up with a C-shaped foot that would take the weight applied on the heel and convert it into energy, thereby stimulating the spring action of the normal foot and allowing the user to run and jump. Once he had the design, Phillips searched for materials that were durable, strong and lightweight. Carbon graphite, a carbon-fiber composite used in the aerospace industry, proved best.

Artificial Joints

From hips and knees to ankles and fingers, different body joints sometimes need replacing due to severe pain or damage. “For decades, the main challenge was figuring out the right materials and mechanics of each artificial joint depending on its use, like bearing heavy loads or requiring a high degree of flexibility,” Ott says.

Hip arthroplasty (creating an artificial joint between two bones) had been attempted for over a hundred years with little success until the 1950s, when British orthopedic surgeon John Charnley pioneered hip replacements. “Charnley’s main hurdle was finding a material that was strong and durable, yet also created minimal friction against the bone,” says Ott. He designed an artificial hip using polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE, also known as Teflon) for the cup socket, which led to less friction.

The first artificial hips, such as these, were heavy and primarily mechanical in nature. The cup and ball are the rotating parts of the joint and the long piece is the stem that anchors the joint within the femur. (Artificial Hip, early 1970s. Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History)

However, by 1962 Charnley realized that PTFE was not a suitable material as it showed signs of wear and reacted with soft tissues. Seeking alternate materials he found high molecular weight polyethylene and, after years of observing the evolution of new hip implants made of this material, he announced the discovery to the medical community. By the late 1980s, total hip replacements had become and continue to be a routine procedure.

*Signed into law on July 26, 1990, by President George H. W. Bush, the Americans with Disabilities Act is one of the most significant civil rights documents in American history. Its purpose was to end discrimination, reduce barriers to employment and ensure access for people with disabilities.

Artificial Joints