By Brendan L. Smith

Public Enemy in 1987 by Jack Mitchell. (Image courtesy Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture)

In the late 1970s, hip-hop burst onto the scene in the Bronx in a cultural explosion of rapping, breakdancing and beatboxing, but it didn’t happen in a vacuum.

Hip-hop built on traditions developed over decades by African-American musicians, dancers and artists. An engaging photo exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture explores those ties through the pairing of photos of hip-hop pioneers with their predecessors.

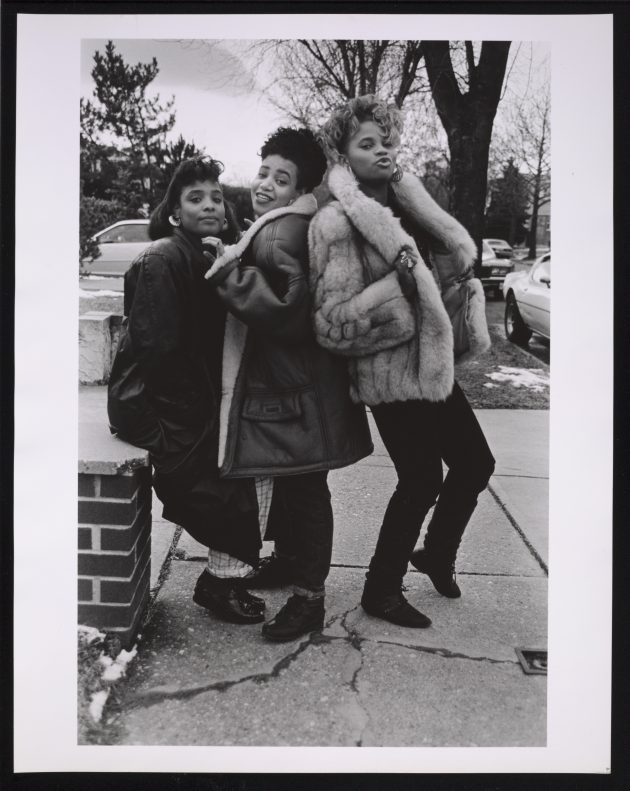

Salt-N-Pepa outside Bayside Studios on Feb. 6, 1989 by Al Pereira. (Image courtesy Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture)

“It shows how hip-hop went from a Bronx-based cultural expression to a global billion-dollar industry,” says Rhea L. Combs, the museum’s curator of photography and film.

“Represent: Hip Hop Photography” explores four themes of how identity, creativity, activism and community influenced elements of hip-hop, including DJs, MCs, break-dancers, and graffiti artists.

“Hip-hop is dynamic, it is a culture. It’s not just music,” Combs says. “It’s an embodiment of a lifestyle. It’s an expression of joy and frustrations, of resilience and community activism.”

KRS-1 & Ms. Melodie, Bronx 1988, by Janette Beckman. (Image courtesy Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture)

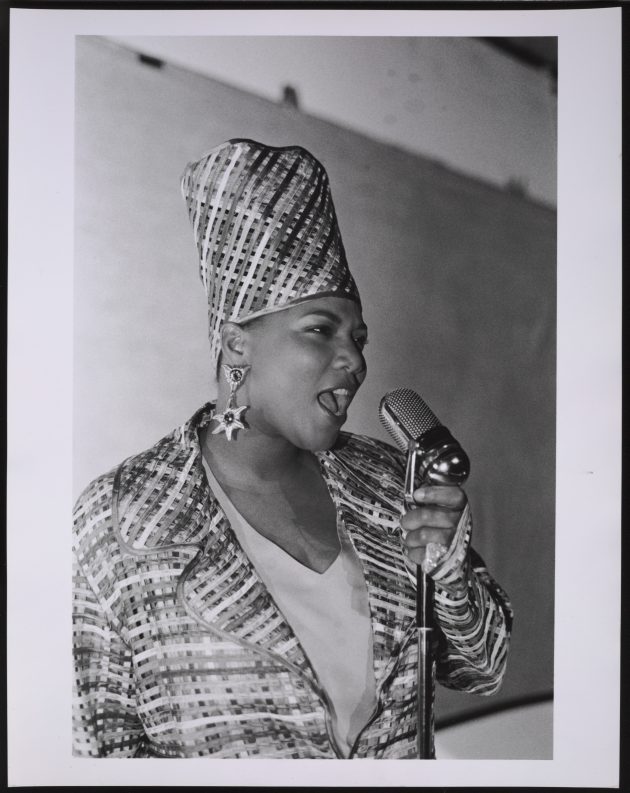

The first pair of photos in the Identity section of the exhibition features rapper Queen Latifah juxtaposed with Gladys Bentley, a lesbian blues singer who dressed in men’s clothes in raucous performances in Harlem speakeasies in the late 1920s and 1930s. In the photos, Bentley is wearing a tuxedo and top hat while Queen Latifah has donned a plaid jacket and tall hat. Separated by decades, both women faced racial discrimination and questions about their sexual orientation.

“That particular pairing is quite striking because they not only have an incredible resemblance to each other, but their pose and hats are similar,” Combs says. “They are almost like doppelgangers.”

Red, white, yellow, and blue Nike sneakers worn by Big Boi of Outkast, 2005-2006. (Collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture)

The exhibition covers just a small fraction of the Eyejammie Hip Hop Photography Collection, more than 400 photos by 59 photographers documenting hip-hop culture that was acquired by the museum in 2015. The collection was compiled by music journalist Bill Adler, who served as publicity director for Def Jam Recordings from 1984 to 1990 where he worked with the Beastie Boys, Run-DMC, Kurtis Blow, Public Enemy, and countless other hip-hop artists. The collection was shown at Adler’s Eyejammie Fine Arts Gallery in New York City between 2003 and 2007 before he closed the gallery in 2008.

The exact origin of hip-hop in the Bronx is still debated, but the breakthrough 14-minute hit Rapper’s Delight by the Sugarhill Gang in 1979 revealed how hip-hop was already entrenched in the New York scene before the 1980s. The lyrics include, “I said a hip hop, hippie to the hippie, the hip hip a hop and you don’t stop, rock it out.”

Photograph of Andre 3000 and Big Boi of Outkast in 2004 by Janette Beckman.

silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper. (Image courtesy Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture)

The most exuberant pairing of photos in the exhibition revels in the way music transports us to a different state of being. Famed jazz musician Lionel Hampton raises his drumsticks in the air and shouts at a smiling crowd, some with their arms outstretched toward the stage, just like in a photo of rapper LL Cool J holding a record above leaping fans at Def Jam’s introductory showcase held at Benjamin Franklin High School in New York in 1984.

In a more subdued moment, a photograph of rapper Big Daddy Kane from 1989 shows him getting a trim of his high top haircut by a shirtless friend wielding an electric razor. It is paired with a 1950s photo by photographer Teenie “One Shot” Harris of an African-American barbershop, which often served as communal meeting spaces.

Queen Latifah on the set of the “Fly Girl” video on June 23, 1991, taken by Al Pereira. (Image courtesy Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture)

The National Museum of African American History and Culture has more than 19,000 photos in its collection dating from the 1840s. It was important to Combs to find relevant historical photographs to display with the contemporary hip-hop images, and to demonstrate the connection this art form has with other periods and genres. While some of the photos show the big names of hip-hop, others feature less well-known figures, such as graffiti artist Rammellzee who tagged New York subway cars in the 1970s and developed elaborate masks and costumes for his own hip-hop performances.

Nas under the Queensborough Bridge in 1993, by Danny Clinch. (Collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, Courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment)

On three video tables in the middle of the exhibition, visitors can scroll through hundreds of other photos from the Eyejammie collection, opening a wider window into hip-hop culture. One wall also is filled with memorabilia, including a graffiti-covered New York subway car door, spray paint cans, a Kangol cap, and vintage flyers. A video screen shows snippets of “Graffiti Rock,” a short-lived hip-hop based TV variety show, and “Wild Style,” the first hip-hop movie centered around graffiti artists.

“For s0me people, it might take them back down memory lane; whereas for others, it can provide a moment to make connections that otherwise might not have been considered.” Combs adds.