Many traits unique to humans were long thought to have originated in the genus Homo between 2.4 and 1.8 million years ago in Africa. A large brain, long legs and the ability to craft tools along with prolonged maturation periods were all thought to have evolved together at the start of the Homo lineage as African grasslands expanded and Earth’s climate became cooler and drier. Now a paper published in Science today outlines a new theory that the traits that have allowed humans to adapt and thrive in a variety of varying climate conditions evolved in Africa in a piecemeal fashion and at separate times.

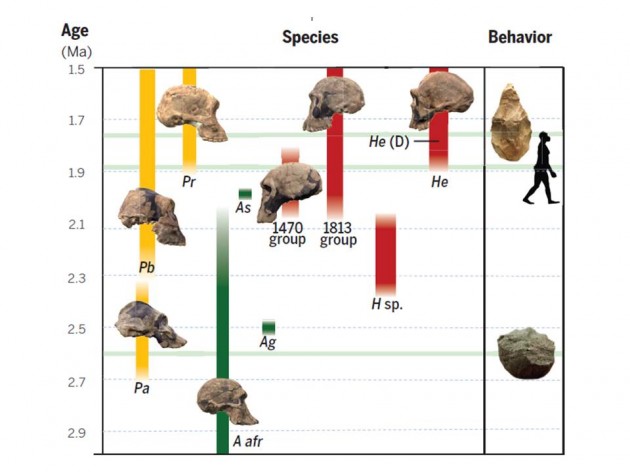

These fossil skulls, representing pre-erectus Homo and Homo erectus, exhibit diverse traits and indicate that the early diversification of the human genus was a period of morphological experimentation. (Photos: Kenyan fossil casts – Chip Clark, Smithsonian Human Origins Program; Dmanisi Skull 5 – Guram, Bumbiashvili, Georgian National Museum)

New climate and fossil evidence analyzed by a team of researchers suggests that these traits did not arise as previously thought, in a single package in response to one specific climatic trend. Rather, these defining Homo traits developed over a much wider time span in response to a much more climatically variable environment, with some traits evolving in earlier Australopithecus ancestors between 3 and 4 million years ago and others emerging in Homo significantly later. The research team includes Smithsonian paleoanthropologist Richard Potts, Susan Antón, professor of anthropology at New York University, and Leslie Aiello, president of the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research.

“The traits that typify our own species Homo sapiens weren’t there right at the beginning of the evolution of the Homo genus; instead, humanness evolved in much more of a mosaic pattern,” explains Potts, curator of anthropology and director of the Human Origins Program at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

“Climate instability we have found would have translated to major shifts in resource availability including fresh water and food. This instability favored genetic traits and behaviors that promoted the evolution of flexibility in how well early humans responded to change. This is quite different from the idea of adaptation to a particular ancestral habitat and is a very important change in our thinking” Potts added.

A large brain, long legs, the ability to craft tools and prolonged maturation periods were all thought to have evolved together at the start of the Homo lineage in response to the Earth’s changing climate; however, scientists now have evidence that these traits arose separately rather than as a single package. (Image courtesy Rick Potts, Susan Antón and Leslie Aiello)

To reach these conclusions, the team took an innovative research approach, including developing a new climate framework based on the Earth’s astronomical cycles from 2.5 million to 1.5 million years ago. This paleoclimatic data was integrated with new fossils and understandings of the genus Homo, archaeological remains and biological studies of a wide range of mammals (including humans). However, it was the recently discovered skeletons of Australopithecus sediba (~1.98 Ma) from Malapa, South Africa, that really cemented the idea for Potts that the evolution of the Homo genus involved a period of evolutionary experimentation and mixing of traits.

“A. sediba possesses a bizarre combination of features. It has a really small brain, the size of a chimpanzee’s, but also a human-like hand. It also has aspects of the face that resemble the genus Homo but has a foot that doesn’t look anything like the genus” Potts explains. “This makes sense from the standpoint of the environment at the time, where habitats were fluctuating between more wooded and more open grassland landscapes due to shifting intensity of wet and dry periods. Small populations would have become isolated at times and later merged, which would have lead to a novel evolutionary combinations of traits.”

This chart depicts hominin evolution from 3.0-1.5 million years ago and reflects the diversity of early human species and behaviors that were critical to how early Homo adapted to variable habitats, a trait that allows people today to occupy diverse habitats around the world. (Image courtesy Rick Potts, Susan Antón and Leslie Aiello)

We live today in a very unusual period where there is only one species that exists in our evolutionary tree. Multiple species of Homo are known to have lived concurrently during the earlier time of morphological experimentation. Along with the climate and fossil data, evidence from ancient stone tools, isotopes found in teeth and cut marks found on animal bones came together in this research to depict how these species may have coexisted.

“Taken together, these data suggest that species of early Homo were more flexible in their dietary choices than other species,” Aiello said. “Their flexible diet—probably containing meat—was aided by stone tool-assisted foraging that allowed our ancestors to exploit a range of resources.”

Evolutionary and historic climate studies not only shed light on how we came to be, says Potts, but also give us a broader view of current climate change problems.

“These kinds of studies show that we do live on an unstable Earth in terms of its climate, however, humans are adding totally new influences to the environment in ways perhaps more precarious than we even thought.”

“Human features were selected for adaptability, but our earlier ancestors show there have always been limits to that. Our astonishing ability to adjust to new and changing circumstances is something that I think gives us some hope for the future,” Potts says.

“The question ahead for human beings is whether we can use our capacity for technology, culture and social interaction to a sufficient extent to avoid the kinds of precarious situations even members of our own evolutionary history faced in their past,” he added.

The team concluded that the flexibility demonstrated by our ancestors to adjust to changing conditions ultimately enabled the earliest species of Homo to vary, survive and begin spreading from Africa to Eurasia 1.85 million years ago. This flexibility continues to be a hallmark of human biology today, and one that ultimately underpins the ability to occupy diverse habitats throughout the world.

Future research on new fossil and archaeological finds will need to focus on identifying specific adaptive features that originated with early Homo, which will yield a deeper understanding of human evolution.