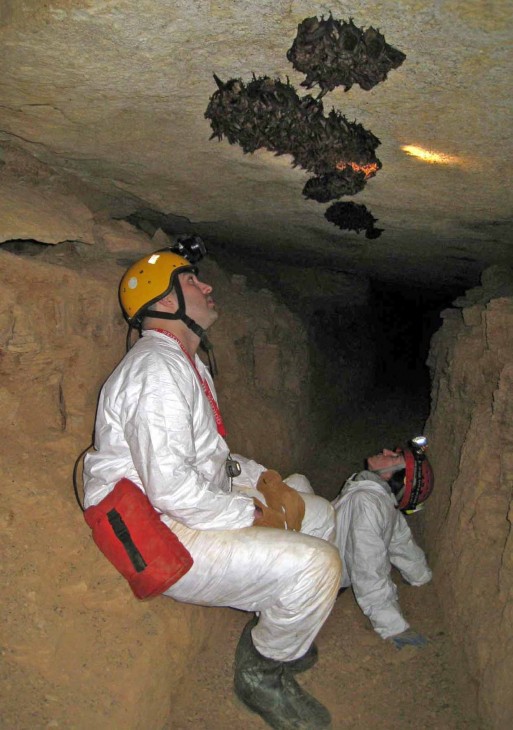

In recent years, an estimated 1 million wild bats have died in the Northeastern United States from white-nose syndrome, a disease characterized by a white cold-loving fungus that invades the skin of the bat, mainly through the muzzle, ears and wings. One consequence of this disease is that the bats lose their fat reserves and ultimately starve.The fungus is now present in caves in West Virginia that support the largest hibernating populations of Virginia big-eared bats in the world. It has spread to 10 states, from New Hampshire to Tennessee, and more endangered bat species are now within its range.

In November 2009, the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park accepted 40 endangered Virginia big-eared bats (Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus) at its Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Va., to establish a security population of these animals and scientifically develop husbandry practices.The possible extinction of this endangered subspecies, and the loss of its essential role in local ecosystems, were the reasons the National Zoo accepted such a high-risk project. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service funded this and other research projects focused on white-nose syndrome and bat survival. The West Virginia Division of Natural Resources has also assisted with the project.

Efforts to keep the bats alive have proved challenging and since November the majority have died. But the lessons Zoo scientists are learning will help save these, and other, insectivorous bats in the future.

Eleven bats remain in the National Zoo’s colony. The initial challenge the team faced was how to feed the animals. Virginia big-eared bats, which are a subspecies of the Townsend’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinuss townsendii), eat while flying. While some in the security colony successfully learned to eat meal worms out of pans, others did not, sometimes resulting in their deaths. Some of the bats that ate mealworms did not adequately groom themselves, which resulted in dermatitis (inflammation of the skin). Others developed foot, toe and digit problems that, in part, may have caused deadly bacterial infections that spread rapidly through their blood despite treatments with antibiotics and fluids.

A Virginia big-eared bat hangs from the roof of a cave. (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service photos)

“Virginia big-eared bats face an imminent threat from white-nose syndrome,” says Jeremy Coleman, the national white-nose syndrome coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Developing a successful captive breeding program is a reasonable precautionary step to ensure the long-term viability of the subspecies. The Smithsonian’s National Zoo is the only organization to accept the challenge of this risky, groundbreaking, but essential endeavor.”

Because it is extraordinarily difficult to maintain insect-eating bats in captivity, extensive planning and preparations went into designing this project. The National Zoo formed a bat care team made up of biologists, husbandry and animal care specialists, veterinarians and a nutritionist who relied on protocols developed by the Virginia Big-Eared Bat Group convened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The team worked around the clock to care for, and learn from, the colony.

“We expected some of the feeding challenges,” explains David Wildt, head of the National Zoo’s Species Survival Center. “But we were surprised to learn how sensitive this particular subspecies of bat is. Even the smallest change in environment or husbandry practices seemed to affect the ability of the bats to adapt to their new environment.”

National Zoo researchers found that bats learned to eat from the bowl faster when confined in a small enclosure for a few hours. In the future, scientists can use this information to better provide for the needs of the subspecies in captivity. The bat team also has learned a great deal about enclosures and the medical care required for insectivorous bats in captivity.

“Faced with the possibility of white-nose syndrome eliminating the entire subspecies, we took decisive action to attempt to protect the bats,” Coleman says. “Together with the Zoo, we will examine this project, take what we have learned and be ready to apply it to captive propagation projects in the future.”

White-nose syndrome continues to devastate wild bat colonies. To learn more about white-nose syndrome on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s white-nose syndrome page.