Most galaxies have a huge black hole at their centers. Our Milky Way, for example, has a central black hole as massive as three million suns. When two galaxies collide and merge, their black holes should eventually do the same, drawn together by gravity. Yet we don’t see many galaxies at an intermediate stage with double black holes.

Smithsonian astronomers have just discovered a rare example of a galaxy that appears to have a pair of giant black holes. Now they are trying to determine if those black holes are partners tied together by gravity, or if one of the two has been kicked out in a cosmic breakup.

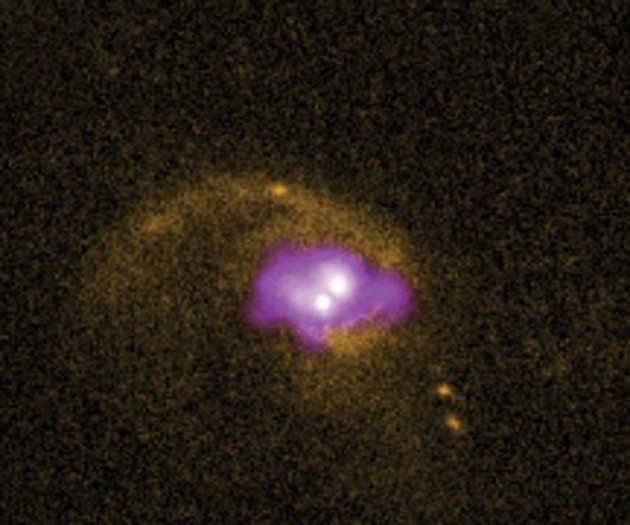

This photo of a distant galaxy combines visible light from the Hubble Space Telescope (orange) with X-rays from the Chandra X-ray Observatory (purple). The two bright spots at center may mark two black holes. The one at lower left may fly out of its galaxy and never return.

“Either way, we’ve found something unusual, something exciting,” says Francesca Civano, an astronomer at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. She leads the team that is studying the unique galaxy.

To find a rare object, you have to search a wide area. NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope recently completed its largest ever survey—named COSMOS—of the universe, spending 1,000 hours photographing a patch of sky eight times the size of the full moon. The same region was surveyed with NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, which excels in spotting black holes. (A black hole emits no light, but its surrounding gas gets so hot that it shoots out X-rays which Chandra can detect.) Civano and her colleagues sifted through the two surveys, looking for light sources visible to both spacecraft.

This artist’s conception shows a black hole (lower left) being flung from the center of a galaxy, carrying some of its surrounding accretion disk along for the ride. Astronomers believe they have found such a “recoiling” black hole, speeding outward at 3 million miles per hour. (Image: Javiera Guedes)

Among the thousands of galaxies detected, one stood out to Civano’s keen gaze. It displayed a curving “tail” of stars, gas and dust, which is a sign of a recent galaxy merger. It also held two bright points of light. Additional observations suggested that each of the bright spots marks a powerful black hole. They are separated by about 8,000 light-years, or 47,000 trillion miles—a third of the distance between our sun and the center of the Milky Way.

Astonishingly, the two black holes are flying apart at a speed of 3 million miles per hour, or 830 miles per second.

Some scientists think that the two black holes are engaged in a cosmic dance, waltzing around each other as they spiral together. Powerful gravity tugging the two black holes could twirl them very rapidly despite the distance between them.

However, Civano believes that one of the black holes was ejected from its host galaxy in a high-speed cosmic breakup. Einstein’s general theory of relativity predicts that when two black holes merge, they emit gravitational waves, which carry away energy and momentum. If that energy blasts more strongly in one direction, the merged black hole will get a kick in the opposite direction—a process called recoiling.

If one of these two black holes is indeed the result of a merger, then the galaxy must have once held three black holes. Such a system is even more rare than galaxies with double black holes, but not impossible. It would result if two galaxies merged long ago and their black holes stalled far from each other until a third galaxy entered the picture, combining with the first and stirring things up.

Discovering a recoiling black hole would be a lucky achievement. “Recoiling black holes are hard to find because there are few, and they are difficult to detect,” Civano explains.

To create a recoiled black hole, the circumstances have to be just right. When a black hole gets a very weak kick, it does not travel far and blends into the background of its galactic center. A very strong kick, however, can cause it to fly out of the galaxy so quickly that it would have no obvious association with its former home. It may not even be able to drag enough material with it to be visible to the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

“If this is a recoiling black hole, we caught it at just the right time,” Civano says.

Further study should help astronomers to select between the two leading interpretations of this black-hole mystery.