By Grace Aldridge Foster

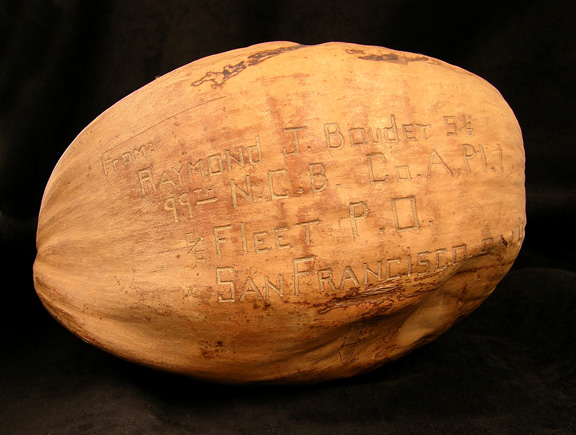

Raymond Boudet, stationed in Hawaii with the Navy during World War II, sent this coconut to his wife in Springfield, Mass. He wired a postage tag to it and carved a love letter into the hard exterior of the fruit. Boudet’s wife Marie donated the coconut to the National Postal Museum in 1995. (Image courtesy National Postal Museum)

When most people think of a letter, they picture handwriting on a piece of paper. But according to experts at a forum hosted by the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum in March, a “letter” can take many forms: voicemails, emails, audio recordings and even a carved coconut.

Raymond Boudet, who was stationed in Hawaii with the Navy during World War II, sent a coconut to his wife in Massachusetts. He wired the postage tag to it and carved a love letter into the hard exterior of the fruit. Boudet’s wife Marie donated the coconut to the National Postal Museum in 1995, where it is part of postal history.

The material, it turns out, is totally immaterial when defining what makes a letter. It’s not the medium that determines this genre, but the anticipation of a future audience and the way a letter is sent. And letters, whatever their form, tell a story.

Irene Donnelly decorated this patriotic stationery with a blue star signifying her sweetheart Charles Eggeling’s deployment. She began it on Nov. 7, 1918 in celebration of the news that the war had ended, however, the official ceasefire was not signed until Nov. 11, 1918. This letter was in the National Postal Museum exhibition “In Her Words: Women’s Duty and Service in World War I.” (Courtesy Center for American War Letters Archives, Leatherby Libraries, Chapman University)

“Letters are the basis of every archive,” said panelist Thomas Levin, a professor from Princeton University, at a recent meeting of the Smithsonian Material Culture Forum. The Forum provides researchers with regular opportunities to meet colleagues in other disciplines and museums, to share information about their fields, consider different directions in their research, or to develop new collaborative projects.

Letters are highly valuable to those who study history and material culture—the analysis of physical objects and how their production, consumption and circulation affect culture.

Sometimes a letter’s sender or receiver was famous; other letters contain historical record of some event. Letters are also important because they preserve types of handwriting and different languages. And occasionally, they are inscribed in unusual materials.

Marie Boudet was likely happy to get a coconut in the mail, but letters were not always so warmly received.

It wasn’t until the introduction of the postage stamp in 1847 that letters came to be thought of as gifts, explained Lynn Heidelbaugh, who recently curated two exhibits on letters at the National Postal Museum. Before that, a letter’s recipient was responsible for paying for it, which meant that getting a letter was often viewed as a burden.

The financial burden shifted from receiver to sender in 1847, completely changing the culture around letters.

A 1974 letter by German artist Hanne Darboven to her art dealer Leo Castelli. filled with gently undulating lines of script. (Image courtesy Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art)

Mary Savig, curator of manuscripts at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, presented a handwritten letter that looks conventional when viewed from a distance—but up close, it is far from traditional.

German artist Hanne Darboven wrote letters that didn’t have many words beyond a standard heading. Yet her pieces are instantly recognized as letters because of their format.

In this one, written to her art dealer Leo Castelli in 1974, Darboven wrote the date and location at the top of the paper. She then wrote a series of looping numeral ones descending in rows down the page, ending with an infinity sign. They look like beautiful, gently undulating lines of script, but they are devoid of an explicit message.

“For Darboven, her lack of text, her lack of words is really a gift to the recipient,” Savig said. “She’s not saying anything, but the fact that she’s showing that she’s taken the time to sit down and work out these formulas or just the ones over and over again until infinity … are still showing the recipient that her presence is there on paper, and that she wants to share that with them.”

In this 1817 letter in the Smithsonian Institution Archives, Thomas Jefferson expresses his gratitude for being appointed an honorary member of the Columbian Institute, a literary and scientific society in Washington.

As Darboven’s letters show, the act of writing and sending a letter often shows tenderness and care for a loved one. People are driven to communicate with each other, but the way they do it changes with the conditions and culture of the times.

Before voicemail, there were gramophonic letters.

Gramophonic letters, which Levin calls “phono-post,” were like an early example of the audio messages we now carry on our devices. Sending voice records through the postal service was a cheaper alternative to long-distance phone calls and between the 1920s and 1960s, hundreds of thousands of acoustic letters were sent and received.

Levin described an audio letter that an American soldier at a USO base recorded for his sweetheart during World War II. This “recorded message from your man in service”—as it says on the envelope—was sponsored by Pepsi-Cola. Such sponsorship was common at USO bases, where lots of gramophonic letters were recorded.

This Pepsi Cola sponsored Recordisc record was recorded by Clarence Melville Beasman in 1943 at Camp Phillips, Kansas, and mailed to his parents in Reisterstown, Maryland. It begins with an unidentified speaker saying: “Hello Mr. and Mrs., C. M. Beasman, of, Reisterstown, Maryland. The Pepsi-Cola Company are very happy to send you the voice of your soldier son, corporal in the US Army, Clarence M. Beasman. Here he is. Click image to learn more. (Image courtesy PhotoPost.org)

Like many traditional letters, these recordings were directed to more than one recipient. Though the content might ostensibly be directed to a sweetheart, a sender often assumed the receiver’s family would listen in too, or even that the message would be published in a local newspaper.

Relatively few gramophonic letters were saved, at least until Levin began a project to collect and preserve them in 2010. People would send them back and forth, recording over the older messages each time. Old letters were erased, and the materials degraded with time and use.

Now, Levin rarely even plays the discs he’s collected; he digitizes them, and then stores the physical records for posterity.

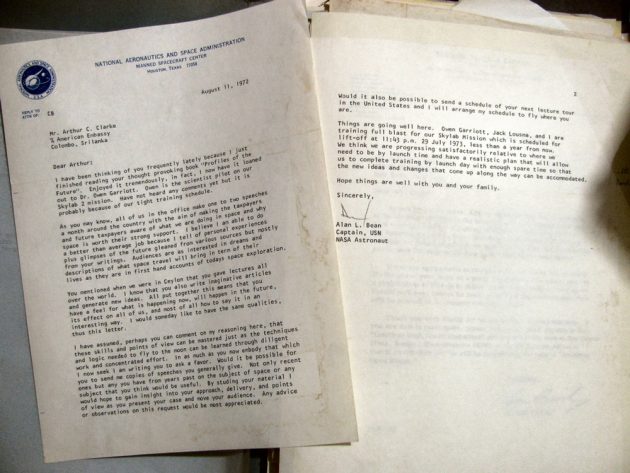

This 1972 letter in the National Air and Space Museum Archives is from NASA astronaut Alan Bean to author Arthur C. Clarke (Image courtesy National Air and Space Museum)

It is increasingly necessary to preserve physical letters now that there are fewer and fewer of them. Gramophonic letters have long been a thing of the past, and in the 21st century people often forego handwritten notes for quicker, easier methods like emails, text messages and video calls.

Since contemporary letter forms are more ephemeral than letters of the past, scholars are left to wonder: What will archives contain in the future? What will future historians study to learn about our intimate communications today?

Savig, a Star Trek fan, has a prediction: “Holograms will definitely be the subject of a Material Culture Forum in a hundred years,” she said.