By Sabrina Green

While serving overseas in Australia in 1943, Army nurses of the 268th Station Hospital receive their first mail from home. (Courtesy National Archives)

Throughout America’s history, soldiers have treasured letters and care packages received from loved ones back home. Just how have these precious items reached far-off recipients through the years? What role has the mail played in the lives of the men and women who serve and their families? “Mail Call,” a new exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum, tells the fascinating story of military mail and communications—from the American Revolution to the current war in Afghanistan.

Here, from the exhibition, are five little-known facts about the military mail.

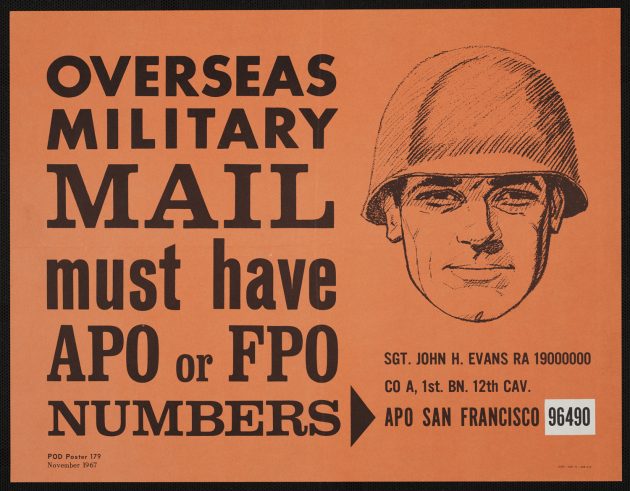

This Vietnam-era poster provided instructions on properly addressing mail bound for overseas military installations. This poster is in the new National Postal Museum exhibit “Mail Call.”

1. The Military Postal Service uses APO and FPO numbers to address letters and packages to soldiers deployed domestically or abroad. APOs and FPOs are numbers tied to a certain troop without using a fixed location. The numbers don’t reveal anything about the troop’s location for security reasons, but it allows the military to track them down since the number is specific to a certain unit.

Personnel aboard USS Nimitz unload mail from an MH-53E Sea Dragon assigned to the “Blackhawks” of Helicopter Mine Countermeasures Squadron Fifteen on June 13, 2003 in the Arabian Gulf. The “Blackhawks” and USS Nimitz were forward deployed to the Arabian Gulf in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. (U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 1st Class Arlo K. Abrahamson.)

2. According to Lynn Heidelbaugh, curator of “Mail Call” at the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum, until 1913, parcels to military personnel overseas could only weigh up to four pounds. After this restriction was increased to 70 pounds, military families were able to begin sending what we know today as care packages. Many of these include the comforts of home, like food, blankets, and other things soldiers are bound to miss while away.

American Expeditionary Forces wait expectantly at mail call for letters and news from home to be delivered during the First World War. (National Postal Museum image from the Postal Museum’s new permanent exhibit “Mail Call.”)

3. Soldiers are not to reveal anything about their troop in letters to home, particularly information like location, movement, and information about the wounded. During the World Wars, a unit’s commanding officer was required to read all outgoing mail from his troops to make sure security was not breached.

This March 1919 postcard carries a touching but brief message from a military service member still deployed in France: “The First card to baby from her daddy, and with Lots of Love too.”

4. Heidelbaugh notes the existence of an “honor cover,” which a soldier can mark on a letter to request some privacy from the commanding officer. If used, then the letter is sent to a central location for its contents to be checked by someone who does not know the author before it is sent.

Marine Corporal Richard Luartes took 50 minutes to read this extraordinarily long letter from his girlfriend, 1952. (Image: National Archives)

5. Even in the fast moving digital age, a physical piece of mail can often be “more tangible and meaningful to a soldier” than just seeing loved ones on a computer screen, notes Heidelbaugh. So keep writing those letters to members of America’s armed forces!

“Missing You – Letters from Wartime,” a National Postal Museum video about wartime letters, 1861-2010, expresses the essential connection of mail between military personnel and the families and friends left behind.