By John Barrat

“The Sentry,” Harvey Thomas Dunn, oil on canvas, 1918 (National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

Rough, thick oil pigments layered upon the surface of Harvey Dunn’s 1918 painting “The Sentry” amplify the jagged fatigue in the eyes of a solitary WWI soldier staring out from the canvas. Rifle and grenades close at hand, chest deep in a trench, the intensity of this American’s gaze is haunting.

“You can see the fear and loneliness in his face, yet he remains at his post,” explains Peter Jakab, chief curator at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum and curator of the new exhibition “Artist Soldiers: Artistic Expression in the First World War.” In this painting Dunn, a combat artist, “captures the moment and the realism of World War I,” Jakab adds. Some 4.5 million Americans fought in WWI and each had their own experience. “In ‘The Sentry,’ Dunn isolates the individual experience, which in his paintings, becomes universal.”

Dunn was one of eight professional illustrators commissioned as officers in the U.S. Army during WWI to embed with the American Expeditionary Forces in France and document the activities of American soldiers. “Artist Soldiers,” on display on the second-floor art gallery of the National Air and Space Museum, contains 54 of some 700 sketches and paintings completed by these artists that capture a broad and compelling “in-the-moment” portrait of WWI.

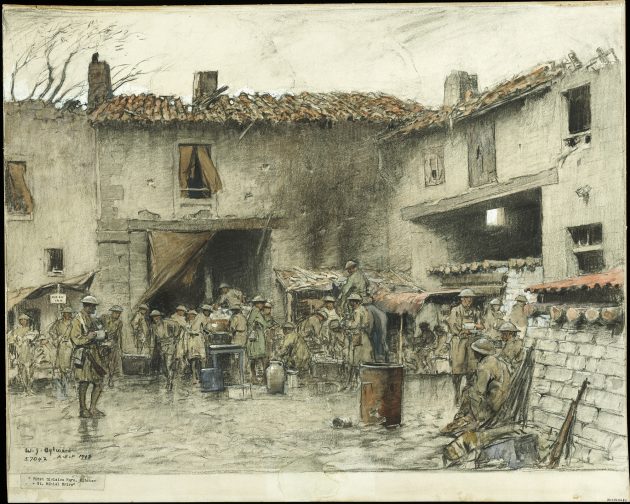

“First Division Headquarters Kitchen, St. Mihiel Drive,”William James Aylward, Charcoal and gouache on card, 1918 (National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

Quarry carving and trench art

Also on view in the Air and Space Museum’s art gallery are 29 images by private photographer Jeff Gusky of stone carvings made by soldiers in underground stone quarries in France where troops took shelter during WWI. With hammers and chisels, soldiers carved portraits, patriotic symbols, messages of longing for loved ones, humor, expressions of religious faith, and even elaborate chapels. Gusky, working closely with local French landowners, reveals this fascinating underground world for the first time.

“The walls of these old quarries became the venue for individual self-expression,” Jakab says of this other section of the show titled “Soldier Artists: Self-Expression in the Trenches.” The carvings range “from the simple and unskilled to extraordinary artistic renderings.”

During several years photographer Jeff Gusky made numerous excursions into underground WWI soldier living spaces to document the stone carvings of the soldiers. This etching illustrates soldiers’ attempts to find respite from battle by following the 1918 World Series between the Boston Red Sox and the New York Yankees. (Photo by Jeff Gusky)

“Artists Soldiers,” also contains numerous examples of trench art: objects that soldiers made from artillery shells, bullets and other military equipment, which further document the creative expression of the participants of the war.

The April 6 opening of this collaborative exhibition with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, which holds the commissioned sketches and paintings in its collection, marked the 100th anniversary of America’s entry into WWI. Other American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) artists whose works appear in the show are William James Aylward (1875–1956), Walter Jack Duncan (1881–1941), George Matthews Harding (1882–1959), Wallace Morgan (1873–1948), Ernest Clifford Peixotto (1869–1940), J. André Smith (1880–1950) and Harry Everett Townsend (1879–1941).

“Forced Landing Near Neufchateau,” by Harry Everett Townsend, charcoal on paper, 1918 (National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

All AEF artists were made captains in the Army Corps of Engineers and given a great deal of freedom to move about during the war. Their artworks were intended to be shown back in the United States to influence American attitudes about the war. “They were renown illustrators and advertising artists—one or two of them came out of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts—selected for their artistic skills, put into military uniform and then placed in different areas of the war, either at the front or to record the troops coming in,” explains Jennifer Jones, a military curator and Chair of the Armed Forces History Division at the American History Museum.

For the AEF section of “Artist Soldiers,” Jakab selected the artworks from the American History Museum’s collection, choosing works that best captured the breadth of subject matter covered by the AEF artists.

“Helping a Wounded Ally,” Harry Everett Townsend, charcoal on paper, 1918 (National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

Transformative experience

“The First World War was a transformative experience for the world,” Jakab explains. “Today, Americans tend to focus more on WWII, because we were more directly involved in it from near its beginning. But really, the 20th century begins with WWI. It saw the first heavy use of a range of technology in war—tanks, machine guns, airplanes, chemical weapons, medical techniques, telephones, photography, telecommunications. The modern military experience was born during WWI.”

A heavily used Harvey Dunn sketchbook in the exhibition reveals how the artists made rough sketches in the field and later polished and finished their works in behind-the-lines field studios or studios in Paris. Once complete, the artworks were turned over to the Army where they were officially registered, and, if deemed appropriate by censors, were sent back to the U.S. to be used in advertisements and media. An Army stamp “OK to print,” appears on the back of many of the prints.

Logistics and support

“Unloading Ship at Bassen Docks,” William James Aylward, Charcoal and gouache on paper, 1919 (National Museum of American History)

Traditionally, war art featured heroic figures and gallantry in battle. These WWI works depict a more complete and realistic view of war. While Dunn and others focused on life at the front, Walter Jack Duncan focused on troops in rear areas who were keeping the army supplied and William Aylward concentrated on the logistics of WWI, especially French ports.

“When most people think of the military they think everybody’s in combat,” Jones says. “Well, in modern war about 80 percent of soldiers are logistics and support and only 20 percent are the tip doing the fighting.” But this war affected everyone in villages, towns and cities and displaced millions of civilians. AEF artists captured a broad experience of the war—including mundane chores such as feeding the troops, interactions with displaced villagers and caring for the wounded. Sections of the exhibition such as “Engineers go to War” and “The Human Cost” depict WWI away from the battlefront.

“American Troops Supply Train,” William James Aylward, oil and gouache on paper, 1918 (National Museum of American History)

Walter Jack Duncan’s 1918 pen-and-ink wash sketch “Newly Arrived Troops Debarking at Brest,” is an eye-opening look at just how many U.S. troops were crowded aboard a military transport ship. Even though the soldiers appear swarming the steam-ship’s deck and must have been desperate to get off, they disembark in an orderly manner.

“It’s in the sketches of the support areas, such as the docks and the hospitals, where more diversity—African American soldiers and women—are depicted,” Jones points out.

War Department Transfer

After the war the Army showed many of the sketches and paintings by AEF artists in New York and Pittsburgh in a traveling exhibition. “Everything was then photographed by the War Department, all the artworks in black-and-white are part of the official records of the Signal Corps at the National Archives,” Jones explains. The originals then came to the Smithsonian; many are labeled “Transferred from the War Department.”

“Camouflaged Barracks for Colored Troops, Airing the Bedding on Sunday,” Ernest Clifford Peixotto

Pen and ink wash on paper, 1918 (National Museum of American History)

“At the end of WWI the United States Army, in particular, was sort of getting out of the business of being an archive and a museum collection,” Jones explains. “Most of the material culture that we have in the Armed Forces collection at the Museum of American History came to the Smithsonian at that time between 1919 and 1922. The Army divested itself of its military material culture, and that included the Schuylkill arsenal collection from the Civil War and post-Civil War period. The Smithsonian received huge army transfers, and these WWI artworks were one of them. We are thrilled that they are out on exhibit once again.”

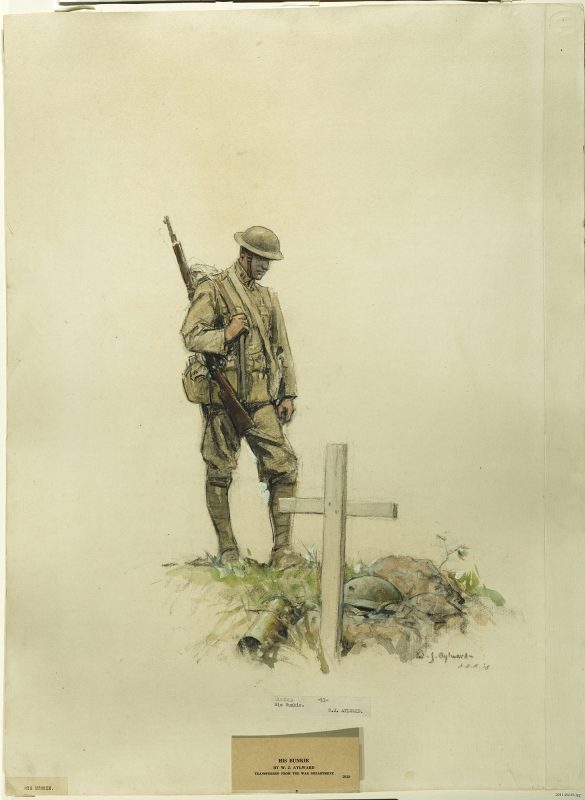

Another gripping artwork on display is the sketch “His Bunkie,” by Aylward. It shows a soldier who has just buried a close comrade. He stands near an artillery shell and helmet on the ground, gazing numbly at an upright white cross. “You can see how the soldier is lost and the way he is looking sorrowfully at his fallen comrade, but he has to go on,” Jones observes.

“His Bunkie,” by William Alyard (National Museum of American History)

Iconic expression

“His Bunkie,” is an iconic depiction,” Jones explains, “of a continued military tradition of grave markings and temporary graves, particularly in America. In every war we’ve fought, it is one of those honored traditions: If you have to leave them behind at least mark where they are. To me, the symbolism in this painting is more about the continuation of a military tradition, the loss in battle, and those left to carry on, than just a piece of art itself.”

In addition, Jones points out, during the museum’s conservation of “His Bunkie,” and other sketches by AEF artists, interesting insights were revealed about their creation. By turning off the lights in her lab and illuminating the sketches with a black light, American History Museum Paper Conservator Janice Ellis illuminated certain areas, highlighting where an artist perfected an original field sketch, erasing some of the outlines and filling in other areas with pastels and gauche. “It is really fascinating to see how some of these images were refined and finished, modifying what the artists had originally sketched in the field.”

“On the Wire,” by Harvey Thomas Dunn, oil on canvas, 1918 (National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

A second oil by Dunn in the exhibition titled “On The Wire,” is a remarkably powerful yet subtle depiction of the brutality of war. In it two exhausted soldiers carry a third on a stretcher along a rise crowned with a barbed-wire barrier shrouded in smoke. Blue and red flowers dot the hillside and the sun is rising as the two soldiers, bogged down by the litter, move through the devastation surrounding them.

“These men were really artists,” Jones adds. “We call them illustrators because they had previously worked as illustrators, and some art historians may not regard them as artists, but when you look at something like “On The Wire” and see the composition and understand the meaning that is embedded in it, it really is art.”