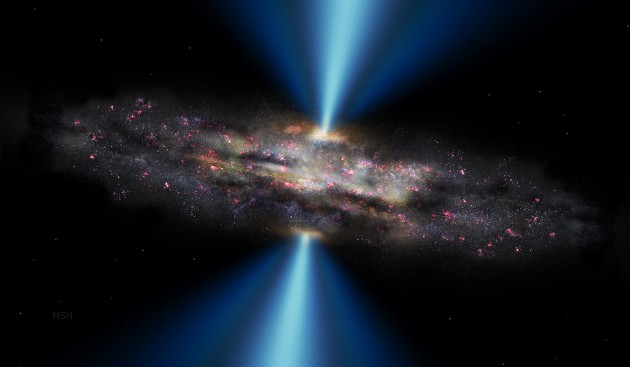

In this illustration a black hole emits part of the accreted matter in the form of energetic radiation (blue), without slowing down star formation within the host galaxy (purple regions). (Illustration by M. Helfenbein, Yale University / OPAC

Researchers have discovered a black hole that grew much more quickly than its host galaxy. The discovery calls into question previous assumptions on the development of galaxies.

The black hole was originally discovered using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, and was then detected in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and by ESA’s XMM-Newton and NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

Benny Trakhtenbrot, from ETH Zurich’s Institute for Astronomy, and an international team of astrophysicists, performed a follow-up observation of this black hole using the 10 meter Keck telescope in Hawaii and were surprised by the results. The data, collected with a new instrument, revealed a giant black hole in an otherwise normal, distant galaxy, called CID-947. Because its light had to travel a very long distance, the scientists were observing it at a period when the universe was less than two billion years old, just 14 percent of its current age (almost 14 billion years have passed since the Big Bang).

An analysis of the data collected in Hawaii revealed that the black hole in CID-947, with nearly 7 billion solar masses, is among the most massive black holes discovered up to now. What surprised researchers in particular was not the black hole’s record mass, but rather the galaxy’s mass. The result was so surprising that two of the astronomers, including Hyewon Suh from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, MA, had to verify the galaxy mass independently. Both came to the same conclusion. The team reports its findings in the current issue of the scientific journal Science.

The distant young black hole observed by the team weighs about 10% of its host galaxy’s mass. In today’s local universe, black holes typically reach a mass of 0.2% to 0.5% of their host galaxy’s mass. That means this black hole grew much more efficiently than its galaxy – contradicting the models that predicted a hand-in-hand development. From the available Chandra data for this source, the researchers also concluded that the black hole had reached the end of its growth. However, other data suggests stars were still forming throughout the host galaxy. Contrary to previous assumptions, the energy and gas flow, propelled by the black hole, did not stop the creation of stars.

The galaxy could continue to grow in the future, but the relationship between the mass of the black hole and that of the stars would remain unusually large. The researchers believe that CID-947 could thus be a precursor of the most extreme, massive systems that we observe in today’s local universe, such as the galaxy NGC 1277 in the constellation of Perseus, some 220 million light years away from our Milky Way.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, controls Chandra’s science and flight operations.

(Source: Chandra X-ray Center, Cambridge, Mass)