Scientists from United States and Slovenia have discovered a new species of spider that is the largest golden orb weaver spider known. Named Nephila komaci, the spider is native to Africa and Madagascar. Females of the species have a body length of 1.5 inches and a leg span of 4 to 5 inches. Males are much smaller than the females. The new spider was described and named in the Oct. 21 issue of the journal PLoS ONE by Jonathan Coddington, senior scientist and curator of arachnids and myriapods in the Department of Entomology at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and Matjaž Kuntner, chair of the Institute of Biology of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts and a Smithsonian research associate.

Scientists from United States and Slovenia have discovered a new species of spider that is the largest golden orb weaver spider known. Named Nephila komaci, the spider is native to Africa and Madagascar. Females of the species have a body length of 1.5 inches and a leg span of 4 to 5 inches. Males are much smaller than the females. The new spider was described and named in the Oct. 21 issue of the journal PLoS ONE by Jonathan Coddington, senior scientist and curator of arachnids and myriapods in the Department of Entomology at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and Matjaž Kuntner, chair of the Institute of Biology of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts and a Smithsonian research associate.

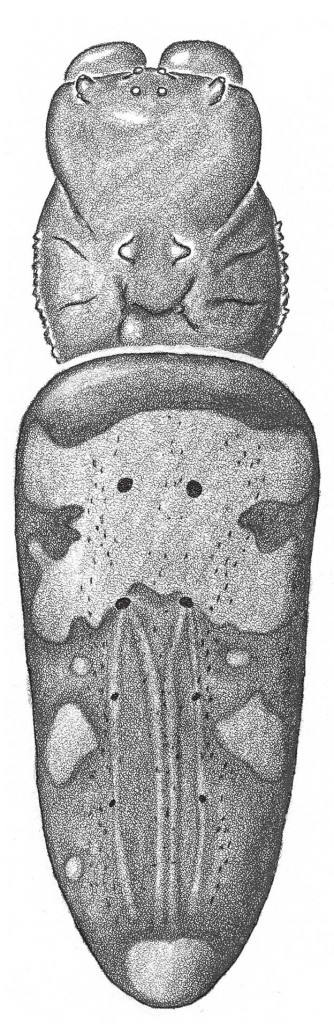

Image: This drawing shows the body of a female N. kmoaci spider, which can reach 1.5 inches in length.

More than 41,000 spider species are known to science with about 400 – 500 new species added each year. But for some well-known groups, such as the giant golden orb weavers, the last new species was discovered in the 19th century.

Nephila, or golden orb weaver spiders, are renowned for being the largest web-spinning spiders. They also make the largest orb webs, which can often exceed 3 feet in diameter. These spiders are also model organisms for the study of extreme sexual size dimorphism and sexual biology.

Giant golden orb weavers are common throughout the tropics and subtropics. The new N. komaci species was first encountered by Kunter in the collection of the Plant Protection Research Institute in Pretoria, South Africa, in 2000. It’s label indicated it had been collected in 1978. Kunter noticed that it did did not match any described species.

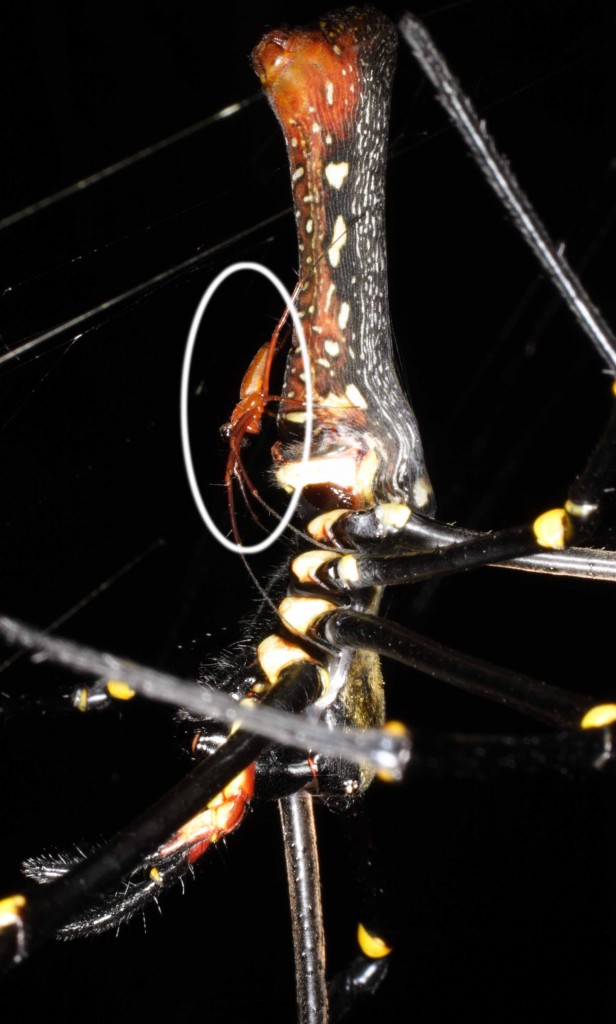

Photo: Sexual dimorphism is a characteristic of gold orb weaver spiders. This image shows a female of the species N. pilipes with a male (inside oval) crawling on her body.

Kuntner, Coddington and colleagues launched several expeditions to South Africa specifically to find this species, but all were unsuccessful, suggesting that perhaps the Nephila specimen was a hybrid or perhaps an extinct species. In 2003 the researchers encountered a second specimen, from Madagascar, in the collection of the Naturhistorisches Museum Wien in Vienna, Austria. No additional specimens turned up among more than 2,500 samples from 37 museums. The species appeared extinct until a few years ago when a South African researcher found a male and two females in Tembe Elephant Park. With this discovery, scientists became certain that the new spider was indeed a new species.

In the PLoS ONE paper, Kuntner and Coddington described N. komaci as a new species, now the largest web-spinning species known, and placed it on the evolutionary tree of Nephila. Scientists believe that as Nephila spiders evolved, the females increased in size and, mainly in Africa, a group of giant spiders appeared. Nephila males, in contrast, did not grow larger over time, but remained about five times smaller than their mates. Males look like “miniatures” next to their mates, yet the males are actually normal-sized; the females are giants.

Kuntner and Coddington urge the public to find new populations of N. komaci in Africa or Madagascar, both to facilitate more research on the group, but also because the species seems to be extremely rare. “We fear the species might be endangered, as its only definite habitat is a sand forest in Tembe Elephant Park in KwaZulu-Natal,” Coddington says. “Our data suggest that the species is not abundant, its range is restricted and all known localities lie within two endangered biodiversity hotspots: Maputaland and Madagascar.”