By Emily Karcher Schmitt

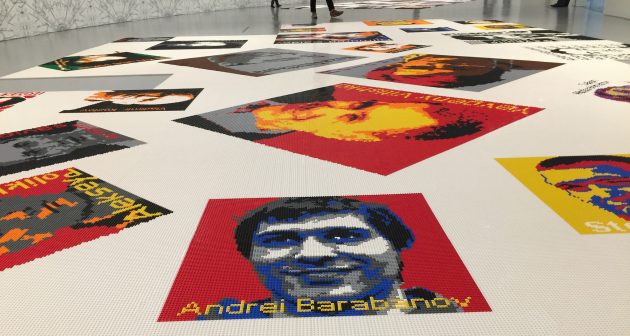

Hirshhorn visitors look over the portraits of international political dissidents made from LEGO bricks in the exhibition “Ai Weiwei: Trace at Hirshhorn” (Flickr photo by Ron Cogswell)

A single, standard LEGO brick—a recognizable shape on any parent or child’s floor—takes up less than an inch of space. It might be just one brick, but it stands for something much larger: the promise of creative expression. As soon as that one brick is added to another, something is built.

Even the youngest of fingers know this intuitively, which is one reason why Chinese artist and political activist Ai Weiwei was inspired in 2014 by his young son’s LEGO bricks to create “Trace,” an exhibition that debuted in Alcatraz in 2014 and features 176 portraits of international political dissidents. It is currently on display at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington through Jan. 1, 2018, alongside a new, 700-foot-long wallpaper installation by Ai titled “The Plain Version of the Animal that Looks Like a Llama but is Really an Alpaca.” It features a mix of Twitter birds, handcuffs and surveillance cameras twisted into an enormous psychedelic graphic inspired by some of the artist’s firsthand experience being detained by Chinese officials in 2011.

“Ai Weiwei is one of the most important artists of our time,” says Hirshhorn Director Melissa Chiu, who recently discussed the current exhibition for Insider. “He is someone who has a sense of the world. He does have a political view, and he puts that forward in the artworks he makes and the messages he sends on social media. He’s one voice amongst many, and he’s gained attention because of his clarity.”

The concept of one voice standing for something larger also applies to the effectiveness of LEGO bricks as the medium for this installation. A single LEGO brick symbolizes, in part, Ai’s emphasis on the power of the individual, building upon each other to create a movement. In a video interview with NPR in June, the artist explained, “I want the image to be seen, and to create that image, we need a language. So LEGO, I think, is the easiest language.”

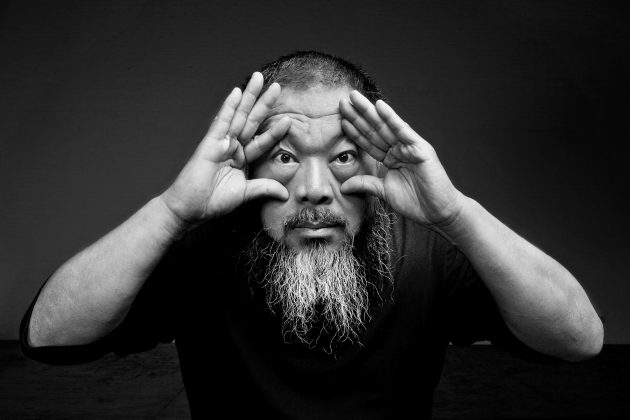

A larger-than-life, black-and-white photograph of Ai greets visitors at the entrance to “Ai Weiwei: Trace at Hirshhorn,” his hands placed at his widened eyes, peering directly outward. Such a welcome is fitting for this larger-than-life icon, recognized worldwide for his public protests against authoritarian suppression of human rights and his provocative shows in museums around the globe in the name of freedom of speech. His middle finger has been photographed against the backdrop of famous landmarks around the world, and it is this juxtaposition of the seriousness of the subject matter against the playfulness of the medium that makes his current exhibition entertaining and thought-provoking.

This 700-foot-long wallpaper installation by Weiwei, “The Plain Version of the Animal that Looks Like a Llama but is Really an Alpaca,” is also in the Hirshhorn’s Ai WeiWei exhibition. (Flickr photo by Victoria Pickering)

Entering the 12,000 square-foot gallery, the space is bright and open. The thousands of LEGO laid out like a meandering pathway on the floor are clean and precise, resembling an almost-digital presentation of vibrant faces and names. Each portrait was assembled by hand from thousands of individual LEGO bricks, by volunteers while Ai was prohibited from traveling outside China in 2014 for the Alcatraz exhibition. In many cases, colors of the flag of each political dissident’s home country are also featured.

It took three weeks for the segments of the LEGO portraits and wallpaper installation to be prepared for display on the Hirshhorn’s second level, and large square cut-outs on the floor remind visitors where structural columns from the Alcatraz display originally stood. The choice to keep the original open spaces for the Hirshhorn exhibition was intentional, Chiu says.

This is not the first time the artist has taken the simplicity of a single object and multiplied it by the millions to make a point. In 2010, his “Sunflower Seeds” exhibition at the Tate Modern museum in London provided commentary on the concept of “Made in China” mass-production by featuring 100 million porcelain shapes, each hand-painted by skilled artisans from Jingdezhen, China to look like identical sunflower seeds.

Ai and his team worked with Amnesty International to identify and research the 176 political dissidents from more than 30 countries featured in the exhibition, most of whom are still incarcerated. When researching the faces of each prisoner, some of the pictures online were highly pixilated as if taken by surveillance cameras, which lent themselves perfectly to LEGO’s intrinsic block design.

In the corner of each of the six areas throughout the gallery, an interactive kiosk allows visitors to delve deeper into the complex stories of each subject: people like journalist Reeyot Alemu from Ethiopia, or singer-songwriter Tran Vu Anh Binh from Vietnam, or the controversial American fugitive Edward Snowden. (All of the names, pictures and stories are available on the FOR-SITE Foundation website.)

Russian dissident Andrei Barabanov is one of 176 activist portraits in Ai Weiwei’s “Trace,” an exhibition constructed of thousands of plastic LEGO bricks, assembled by hand and laid out on the floor. (Flickr photo by Ron Cogswell)

The interactive nature of the exhibition—particularly one that features an artist adept at engaging his audiences in myriad ways—is something Chiu is looking to extend to future commissions. She recently hired Mark Beasley, a curator dedicated to identifying new ways to engage audiences and augment the visitor experience through emerging opportunities in new media and performance art.

“We are looking for works that have some participation value or interactive value,” Chiu explains. “It’s partly driven by where artists are today and they’re making more work that is either performative, interactive or participatory. It is also driven by younger audiences that have an interest in that kind of work, so it’s coming from two directions. And I think that as a museum of contemporary art, that we should be responsive to that.”

Chiu sat down with Ai for a conversation on his exhibition, artistic inspiration and expression—such as his prolific use of social media—at the museum’s annual James T. Demetrion Lecture in June. The most important part of art, Ai said, is speaking up and sharing different points of view. Watch the full interview online.