By Emily Karcher Schmitt

“Early Morning May 20, 1986,” 1986, latex and tar on tile over Masonite. (Private collection, New

York. © Donald Sultan)

A yellow blaze surrounds the black silhouette of a firefighter, who faces the encroaching flames in the painting “Early Morning May 20, 1986.” It is a tale of life and death, but also a tale of tamed versus wild: the black tar of the painting supporting its protagonist alongside a black railing–still intact–as a blinding yellow fire lends light and steals lives with indiscriminate intensity. Will it be this firefighter’s life too?

Windy gray smoke–seen through purposeful smears and contrasting brush strokes–begins to mix with the mustard-yellow fire to signal a dire warning to the heroic figure: There can be life, and there can be death, but there can be no mixing of the two. “Early Morning May 20, 1986” is one of 12 works from the exhibition “Donald Sultan: The Disaster Paintings,” currently on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Each painting is eight feet-square, gridded onto Masonite tiles with linoleum and intricately layered and sculpted in smoky mixtures of tar, paint, and latex. Sultan, known for his expertise as a painter, sculptor, and printmaker, created them to convey mostly hulking man-made structures such as industrial plants and train cars that can crumble in mere moments during accidents.

“Veracruz Nov 18 1986,” 1986, latex and tar on tile over Masonite. Matthew and Iris Strauss

Collection, Rancho Santa Fe, California. © Donald Sultan

Each painting tells a different story, but the series theme is both complex in its paradox yet simple in its rhythmic nature: Humankind destroys itself. Repeatedly.

“On an individual level, they’re very powerful things,” says Sarah Newman, the museum’s James Dicke Curator of Contemporary Art. “But when you take them as a group, and a series, they give you a sense of culture and its fragility. The individual moments of horror fade into a larger wave.”

That horror is not jarring at first glimpse. The presentation as a whole is almost reassuringly simple, with each painting methodically leading to the next, and many swirled with similar tones of black and yellow.

Individually, however, they show stories of terror and tragedy in the midst of everyday life. A visitor begins to feel it. The toxic concoctions gouged as near-sculptures on a painting, the dripping yellow, and the detailed architecture becomes almost oppressive, as though Sultan invites the casually comfortable museum visitor to dare squint through the smoke and soot, gasping in the caustic air, bearing firsthand witness to each disaster.

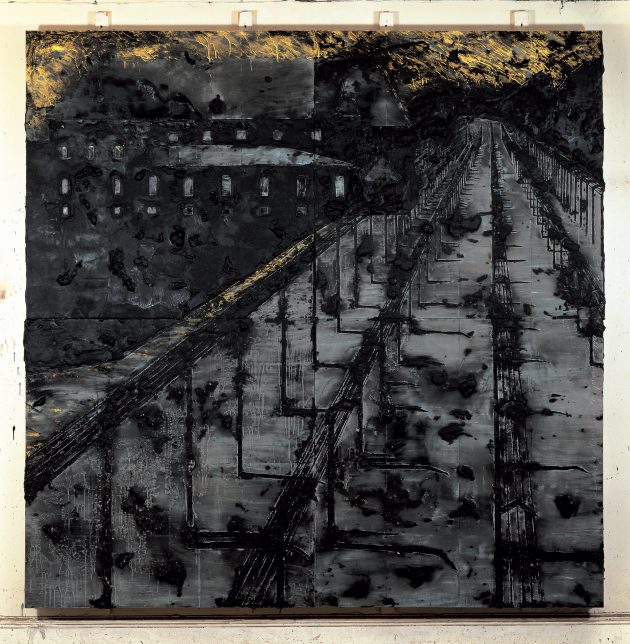

“Polish Landscape II Jan 5 1990 (Auschwitz),” 1990, latex and tar on tile over Masonite. The Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York, Gift of the Broad Art Foundation. © Donald Sultan

In the painting “Venice without Water June 12, 1990,” Sultan has created a bleak scene in blue-gray and black showing stark black piers sticking up out of the canal mud as an empty naked bridge sits gaping in the background as if aghast at its misfortune. In the foreground, paint drips stream down the face of the painting like tears oozing from where water formerly flowed; and yet, in true paradoxical form, the buildings in the background are so intricate and precise, they could be mistaken for a photograph.

In the exhibition the works are coupled with Sultan’s quotes on human catastrophe–a perspective he gained from newspaper stories of the 1980s, global tragedies that inspired each of these paintings and from his firsthand experience near ground zero in Manhattan on Sept. 1, 2001. Visitors entering the gallery are greeted with these words from Sultan: “The series speaks to the impermanence of all things. The largest cities, the biggest structures, the most powerful empires–everything dies. Man is inherently self-destructive, and whatever is built will eventually be destroyed…That’s what the works talk about: life and death.”

This essence of paradox is what first compelled Sultan to begin his first “Disaster Painting,” artwork in 1983, and what propelled his work into a series spanning seven years and a collection of more than 60 pieces. For Sultan, his use of paradox inspired not only his subjects but both his materials and presentation.

“Accident July 15 1985,” 1985, latex and tar on tile over Masonite. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Florene M. Schoenborn Gift, 1986. © Donald Sultan

“To me what is interesting formally about the works is that they are unchanging grids of Masonite tiles, so they seem very stable,” Newman says. “They are heavy squares composed of smaller squares. As much as the paintings are about fire and destruction and drama, they are also incredibly solid and seem like they are not going away. The work feels eternal. Seeing a number of them together reinforces that quality square after square after square.”

In a webcast conversation with Sultan from June 1, 2017, the artist shares with Newman some candid insight into his vision–not only for the series but also of himself as an artist among artists. Known for his keen understanding of art history, Sultan describes both his nonconformist approach to painting and his desire to push traditional definitions of landscape and perspective to new levels.

Newman says the American Art Museum is deliberate in collecting and displaying work from artists like Sultan, who consciously think about their place in history. “In the context of our collection, it’s always interesting to look at artists who are actively thinking about the past and traditions of representation. There are so many experiences and themes that are a constant, including how people relate to the landscape and the world around them. Artists build on those traditions as much as they are creating something new.”

“Venice without Water June 12 1990,” 1990, latex and tar on tile over Masonite. North Carolina

Museum of Art, Purchased with funds from the North Carolina Museum of Art Foundation, Art Trust Fund.

© Donald Sultan

The portrayal of these themes of industrial paradox, according to Newman, is itself cyclical as well. “In the early 20th century, you can see so many of the issues that Donald Sultan deals with, the themes that just don’t go away,” she says. In graduate school at University of California, Berkeley, Newman studied early 20th-century American painting and explored the works of George Bellows, who painted the excavation of Penn Station in New York City.

“It is a similar mix of awe at the wonders of modern technology and an awareness of the horrors that are unleashed,” Newman says of the themes portrayed in the “Disaster Paintings.” “It is about taking a step backward at the same time as you are moving forward. Whenever artists are thinking about modernity, there is often an awareness of unexpected forces that emerge at the same time.”

“Double Church Nov 8 1990,” 1990, latex and tar on tile over Masonite. Private collection, New York; on loan to the Butler Institute of American Art. © Donald Sultan

It is this cycle of creation and collapse that Newman says makes Sultan’s current exhibition relevant and timeless. He painted his works in the 1980s–which is why, Newman says, they no longer smell like the tar and other chemicals used to create them–but the lasting message, she explains, is perhaps more pertinent than ever.

“You look around and the numbers of disasters and catastrophes have not abated,” Newman says. “We continue marching into the future, and yet progress and destruction still seem inextricably linked. These are eternal themes.”

SAAM is the third stop on a five-city national tour of “Donald Sultan: The Disaster Paintings,” which was organized by Alison Hearst, assistant curator at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. It is the first time a significant number of these paintings are being exhibited together. The exhibition will be on display in Washington, D.C., through Sept. 4.