By Theresa La

“Think of a lion shrunk to the size of a mouse that needs to eat every 20 minutes or so.” That is a shrew, says Neal Woodman, a U.S. Geological Survey mammalogist who is curator of mammals at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. “Shrews are predators with very high metabolisms, hence their reputation for fierceness.”

“Think of a lion shrunk to the size of a mouse that needs to eat every 20 minutes or so.” That is a shrew, says Neal Woodman, a U.S. Geological Survey mammalogist who is curator of mammals at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. “Shrews are predators with very high metabolisms, hence their reputation for fierceness.”

Woodman is lead author of a recent paper describing a new species of small-eared shrew, Cryptotis monteverdensis, from the Monteverde Cloud Forest in the Tilarán Mountains of Costa Rica, Central America.

Shrews in general and small-eared shrews in particular are shy and quite harmless to humans (but not their prey), Woodman adds. While shrews are found worldwide, small-eared shrews, genus Cryptotis, live only in North, Central and South America. Some species of these shrews, in fact, “can be found in backyards in Washington, D.C., and across the United States. You may have seen one but probably just didn’t realize that it was a shrew.”

Small-eared shrews look like a cross between a mouse and mole but with an anteater’s nose, and have short tails and tiny, invisible ears. They have 30 teeth and are not rodents. In northeastern North America, one species, the Northern short-tailed shrew, has venom in its saliva that it uses to stun prey. This venom gives these animals the unique distinction of being the only poisonous mammal in North America.

For a human, Woodman says, “The most you’d experience from a shrew bite is swelling and redness. But, first you’d have to find one, then you’d have to induce it to bite, and the bite would have to break the skin–in all, an unlikely scenario,” Woodman says. A shrew would much rather run away.

Discovering the new shrew species actually began in 1973, when a single specimen was picked up dead alongside a trail by a Monteverde resident; the specimen eventually ended up in the possession of Woodman’s co-author, Robert Timm, at the University of Kansas. Careful measurement and analysis of the specimen, an adult female, provided evidence that it was a new species.

“Cryptotis parva” or least shrew, lives in the Great Smoky Mountains of North America and belongs to the same genus as the newly named shrew “Cryptotis monteverdensis,” from Costa Rica.

Through the years, Woodman and his colleagues have conducted studies on this specimen, all the while conducting field observations, hoping to spot one alive in its natural habitat. So far, no luck.

“We used a variety of trap types to survey in all major habitats,” Woodman and Robert Timm write in their paper. “Local residents assisted by preserving specimens found dead along trails and roads and brought in by domestic cats. These efforts have added to the total number of shrews and other mammals available for study, although we failed so far to locate a population of the new species.”

With the single C. monteverdensis specimen preserved at the University of Kansas, Woodman says, “we were just holding out hope, waiting to find a live member of the species. We are still hoping that more show up, but we figured it was time to start studying what we had.”

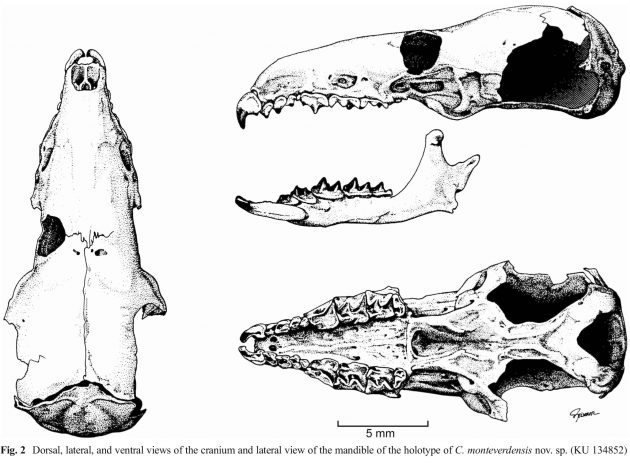

In the laboratory, using the skin, skull, and humerus of the holotype, the scientists evaluated its qualitative characters, comparing its morphology to various other shrew species in the Smithsonian’s collection and a number of other collections throughout the country. Its distinct skeletal morphology set it apart, leading Woodman and Timm to determine it was a new genus and species of shrew. Since 1992, 18 new species of short-eared shrew have been described and named by Woodman or his colleagues. C. monteverdensis is number 19.

The remains on one “C. monteverdensis” was discovered and collected from this region of Costa Rica in 1973. No other specimens have been collected since.

“Unlike any of the other shrews we have found in the region, and to a large part most of Central America, this species had a much larger size and longer tail, and, proportionally large skull,” Woodman explains. “These are unique characteristics for shrews within Costa Rica, but not throughout the region.”

Of unique interest to the researchers was analysis of three long bones in the forelimb—the humerus, radius and ulna—of C. monteverdensis. These bones can be used to infer a lot of information about a shrew’s everyday life, specifically if it is more of an ambulatory or fossorial species. Fossorial species have adaptations that make them better diggers and more likely to live underground.

For C. monteverdensis, its forelimb reveals it is more of an ambulatory, above-ground shrew. It is named after the Costa Rican community of Monteverde, where it was discovered. This region straddles the Continental Divide in the Tilarán Mountains of Costa Rica, and is covered with tropical cloud forest, small areas of secondary forest and a flat, swampy area.

“I wish people knew about this creature – it’s quite an interesting and fascinating one,” Woodman says. “Based on my experience, there are approximately 8 to 10 species in this genus that have yet to be identified.” In fact, there are probably many species of animals, not just those belonging to the shrew family, that live in this region that have yet to been identified, described and named, he adds.

Now, however, the urgency to conduct this research, and identify these remaining species, has escalated due to climate change. The small-eared shrew genus prefers cool temperatures and wet areas. If this region warms up and dries out it could spell disaster for C. monteverdensis and other animals, Woodman says.

A great deal of work remains, not only identifying additional species of small-ear shrews, but also to learn more about the characteristics and habits of known shrew species.