By Michelle Z. Donahue

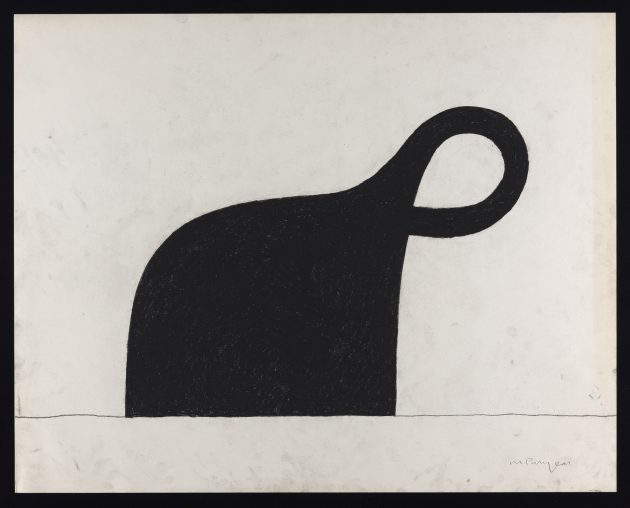

Martin Puryear, “Drawing for Untitled,” 2009, about 2009, compressed charcoal on paper, Courtesy of the artist. © Martin Puryear, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

From the repetition of vaguely familiar human shapes to his copious use of warm-colored woods and matte metals, Martin Puryear’s sculptures are known for their high attention to craft and allusions to a common human experience.

Yet rarely has this Washington, D.C. native’s art been displayed as a collection and never has it been shown together with the paper-based prints and sketches he still produces as part of his creative process.

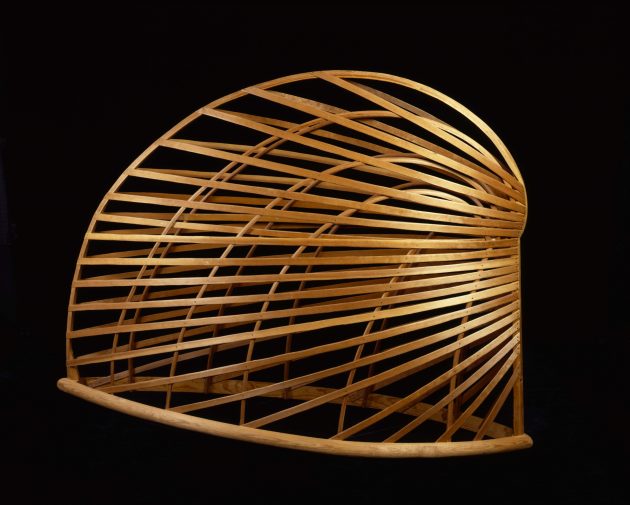

Martin Puryear, “Maquette for Bearing Witness,” 1994, pine, Courtesy of the artist. © Martin Puryear, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. (Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics)

A new exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) changes that dynamic, covering 50 years of the artist’s labors for the first time in a way that gives a glimpse into his artistic approach and influences.

The Smithsonian is the final venue of “Martin Puryear: Multiple Dimensions,” an exhibition that opened first at its organizing museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, and then the Morgan Library and Museum in New York.

For SAAM, Karen Lemmey, the museum’s curator of sculpture, chose to focus on the importance of Puryear’s public art. Several of Puryear’s most recent works happen to be public sculptures—“Big Bling” in New York’s Madison Square Park, “Memorial to Slavery” commissioned by Brown University, and a monument for the Deichman Library in Oslo. All three, along with his older monument “Bearing Witness” for Federal Triangle, are referenced in the exhibition at SAAM.

Puryear’s maquettes, which are small-scale models of a full-sized work, and drawings for “these monumental outdoor sculptures are never just preparatory models. Each one stands alone as a finished artwork while adding to our understanding of his creative process,” Lemmey says. “Seeing these models and drawings together in our exhibition gives us an opportunity to recognize continuities in commissions he completed at different times for sites around the world. His work often invites thought and discourse on important civic concerns, and what better place to do this than through public sculpture?”

Martin Puryear, “Maquette for Big Bling,” 2014, birch, plywood, maple, and 22k gold leaf, Courtesy of the artist. © Martin Puryear, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. (Photograph by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics)

Puryear may be best known in his hometown of Washington, D.C. for “Bearing Witness,” a 40-foot-tall sculpture made of panels of hammered bronze standing guard outside the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center. The exhibition features maquettes and drawings for several of his major outdoor public sculptures, including “Bearing Witness,” and the artist’s new 40-foot-tall “Big Bling,” which debuted May 16 in Madison Square Park in New York City. That colossal work features a large, gold-leaf shackle and is on display throughout 2016.

Another large-scale work featured in the exhibition is “Vessel,” created from curving ship-sized timbers.

Puryear earned his undergraduate degree in fine arts at Catholic University in 1963, then joined the Peace Corps as a volunteer in Sierra Leone from 1964 to 1966. Without a camera in Sierra Leone, Puryear instead produced faithful drawings of villages and their inhabitants, which he sent along with letters home to family.

“For someone who is known for his public monuments, this exhibition is a rare opportunity to see some early drawings from the artist’s personal collection made while he was in Sierra Leone, works he created for himself or for his family,” Lemmey says.

After the Peace Corps, Puryear began his training at the Swedish Royal Academy of Art in Stockholm. His works shift to become less of a mirror, and more of a lens through which he projects experiences in a way that evokes his memories and encounters.

“These prints show Puryear’s origins before he became a sculptor,” says Joann Moser, who helped bring the exhibition to SAAM before she retired as the museum’s senior curator of graphic arts and deputy chief curator. Despite a fire in 1977 that damaged or destroyed many of his early works, the pieces that survive show how some of Puryear’s ideas got started.

Martin Puryear, “Bower,” 1980, Sitka spruce, pine, and copper tacks, Smithsonian American Art Museum, © 1980, Martin Puryear, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

“Bower,” a bent-wood object from SAAM’s collection on display only in Washington, echoes the shape of a Phrygian cap, a garment that dates from the fourth century B.C. that became popularized as a symbol of liberty during the French and American revolutions and at times was also a symbol adopted by abolitionists. While “Bower” was made in 1980, Puryear revisited the shape again nearly 20 years later, from 2001 to 2003, on three untitled prints, and again in 2012.

Martin Puryear, “Phrygian,” 2012, soft ground etching with spit bite, drypoint and aquatint on paper, laid down on paper (chine collé), Smithsonian American Art Museum. © 2012, Paulson Bott Press

“This exhibition provides an exciting look at the persistence and evolution of ideas in Puryear’s work going back to the early 1960s,” Lemmey says. “I am particularly delighted to see ‘Bower,’ one of Puryear’s acknowledged masterpieces from the museum’s collection, situated with works on paper from other collections so we can see how Puryear returned to latticework forms and ideas about shelter across the decades.”

Another form repeated often throughout Puryear’s art is a kidney-shaped ellipse, sometimes looking more like a human head and neck, sometimes more like a teardrop. “Bearing Witness” and “Vessel” both recall this shape, as does “Big Bling” and a smaller, all-iron work, “Shackled,” where the shape appears as a negative space.

Martin Puryear, “Vessel,” 1997–2002, eastern white pine, mesh, and tar, Courtesy of the artist. © Martin Puryear, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Through the familiarity of the forms and materials he uses, Puryear aims to open up discourse about the meaning of the shapes he uses without dictating any concrete meaning.

“I tend not to tell people what they’re looking at when they’re in the presence of my work,” Puryear said at the dedication of his Madison Square Park piece. “I trust people’s eyes. I trust their imagination. I trust my work to declare itself to the world.”

“Martin Puryear: Multiple Dimensions” is on view through Sept. 5, 2016.