By Michelle Z. Donahue

Two rovers are active right now on the surface of Mars: Opportunity, which landed in January 2004, and Curiosity, which started exploration in August 2012. For most of June, these two craft were on stand-down because the sun was between Earth and Mars, blocking most transmissions.

Their drivers, however, weren’t resting. A “day in the life” of the Mars rover drivers does not begin and end with the Earth’s sunrise and sunset; they live their lives according to sols, the 24-hour-and-40-minute solar day of Mars time. This is because the rovers are solar powered, and can only take pictures and operate during daylight hours in local time. Their “drivers” are forever planning about where to head next.

John Grant, geologist with the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, helps lead the daily science planning and operations for both Mars rovers. He’s been involved well beyond the 90 days Opportunity was expected to function; 11 extra years, in fact. Grant and the rest of the team at NASA, the European Space Agency and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., host regular confabs to figure out the rovers’ next moves.

In his office at the National Air and Space Museum John Grant studies digital photographs taken by NASA rovers of the surface of Mars. (Photo by Eric Long)

Grant recently sat down with Smithsonian Science to talk about what it’s like to tootle around on Mars.

Q: What’s it like to drive on Mars?

Grant: Well, for one, there’s no joystick. For the first 90 to 120 days of a mission, you strictly follow Mars time, which is 40 minutes different from Earth’s. So one day, you’d start planning at 10 a.m., but the next day things start at 10:40 a.m. After three months, you’re completely out of sync with Earth time. I help bring the science teams to consensus for what to do on any given day or over longer periods, depending on the rover. To do that, we spend hours on the phone, daily or every other day.

Q: How are Curiosity or Opportunity controlled, then?

Grant: We’ll decide what we want to look at and create activities [like distance to travel, photography or chemical analysis] that fit with the amount of time, power and downlink ability we have. We work with the engineers, who write the code sequences that are sent to the rovers. The rovers receive their commands, wake up, do their work, send their data to the Odyssey or Mars Reconnaissance orbiters [satellites orbiting Mars], which relay the collected data back to Earth. And repeat.

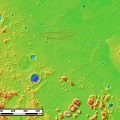

This map shows the route on lower Mount Sharp that NASA’s Curiosity followed in April and early May 2015, in the context of the surrounding terrain. Numbers along the route identify the sol, or Martian day, on which it completed the drive reaching that point, as counted since its 2012 landing.

Q: What are the rovers looking for?

Grant: For Opportunity, it was all about following the water, and looking at the role water had in shaping the Martian landscape. Curiosity’s mission is more related to habitability, looking at whether there are places on the planet where water was persistent and where it might have been habitable. The next rover, planned for 2020, will be focusing more on possible biosignatures, the chemical or physical changes in sediments and rocks caused by life forms that may have been there.

Q: Can you steer the rovers wherever you want?

Grant: No. Sometimes you say, “Ooh! A shiny rock! Let’s go there!” But other times you just have to say, “Yeah, that’s a shiny rock, but we have to stay focused on today’s mission.” You need caution and plodding, but you also need to be adventurous, to get all the viewpoints.

Q: Why is studying Mars important for people on Earth?

Grant: Looking at Mars is a bit like looking back in time. Some surfaces on Mars are three or four billion years old, but on Earth, because of plate tectonics and volcanic activity, much of our planet, including the entire ocean floor, is younger than that. We can’t see our own early record because it’s been destroyed, but we can see it preserved on other planets. The time in the solar system that is preserved on Mars is equivalent to when life would have gotten going here, so we’re looking at how conditions were different on Mars.

This image from the Navigation Camera on NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover shows a sandstone slab on which the rover team has selected a target, “Windjana,” for close-up examination and possible drilling. The target is on the approximately 2-foot-wide (60-centimeter-wide) rock seen in the right half of this view. The Navcam’s left-eye camera took this image during the 609th Martian day, or sol, of Curiosity’s work on Mars (April 23, 2014). The rock is within a waypoint location called “the Kimberley,” where sandstone outcrops with differing resistance to wind erosion result in a stair-step pattern of layers.

Q: Have there been any ‘eureka!’ moments for you?

Grant: Yes! For Curiosity, it was finding mudstones in Yellowknife Bay [in Gale Crater, where Curiosity is currently exploring.] Their chemical and structural properties showed they had been deposited in a lake that might once have been habitable. On Spirit [Opportunity’s twin rover, launched at the same time but stopped functioning in 2010], the right front wheel stopped turning, and we found that it was easier for the rover to drag it along than push it. In one locale, the wheel dug a shallow trench that exposed a brilliant white underneath otherwise uniform browns and reds. The substance turned out to be nearly pure silica, probably deposited from a fumarole or steam vent similar to what might be found in Yellowstone or Hawaii.

Gray cuttings from drilling by NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover into a target called “Mojave 2” are visible surrounding the sample-collection hole in this image from the rovers’ Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) camera. This site in the “Pink Cliffs” portion of the “Pahrump Hills” outcrop provided the mission’s second drilled sample of layered rock forming the base of Mount Sharp.

Q: Do you have a good sense of what Mars as a planet is like?

Grant: The entire surface of Mars is roughly equivalent to the entire above-water land area of Earth. There have been a handful of surface missions to Mars; if you set down in seven places on Earth, how well would you say know the Earth? Probably not very well. We try to look at the geologic story of each place, but we’re scrambling around on six wheels, communicating once a day, and it’s taken us 11 years to do what we’ve done. Although it has been incredibly successful and rewarding, it is slow by the nature of the process.