If you love new animal species and have an Internet connection, chances are you have already seen the beautiful new golden bat species, Myotis midastactus. What you may not know is that the striking, newly described bat species is just one of more than six species being described by Ricardo Moratelli, a scientist at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Brazil) and post-doctoral fellow at Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

Smithsonian Science asks Moratelli what it’s like to be a bat detective searching for new species.

Adult female of “Myotis midastactus” captured at Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, Department of Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Ricardo Moratelli and Don Wilson, mammalogist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, recently named this bat as a new species. (Photo courtesy Marco Tschapka)

Q: Is it difficult finding new bat species?

Moratelli: It can be. I have been working for the last 10 years on the taxonomy of bats of the genus Myotis, which is the most diverse genus of bats in the world. The genus is distributed worldwide and there are more than 110 species. However, my research is focused on the Neotropical (Latin American) species.

Myotis has been considered one of the most difficult Neotropical genera of bats to understand. It is very hard to tell species apart, as they all look very similar and they have very few morphological traits that allow us to see where the species boundaries lie. What makes my job even harder is when museum specimens in collections have been either unidentified or misidentified in the past, making more work for me to figure out what is what.

Ricardo Moratelli in the collections area of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, holds two bats that he has recently helped classify as new species. (Photo by Micaela Jeminson)

Q: What led you to suspect that the Bolivian golden bat was a new species?

Moratelli: Specimens of the Bolivian golden bat have been misidentified as Myotis simus in collections since 1965. But when I compared samples from different localities throughout the entire range of the species, it was quite apparent that there was a new species, as the Bolivian specimens looked so different. The golden fur color really stood out compared to Myotis simus individuals from the Amazon Basin in Brazil, Ecuador and Peru.

The collections from the American Museum of Natural History (in New York) and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History allowed me to compare the morphology of specimens from different localities. The golden bat not only has a distinctive fur color, it’s also larger in size and the skull has several morphological differences. We also did not find specimens of this new species outside of the Bolivian savanna, so we suspect that Myotis midastactus is probably endemic to Bolivia.

Q: How many other bat species have you found?

Moratelli: At the moment I have described six new species of bat and I have at least six more that I am working on describing. One of these species is based on specimens that have been in museum collections for more than a century. When I started this project there were 12 known South American species of Myotis and now there are 19, six of which I have added to the list with colleagues.

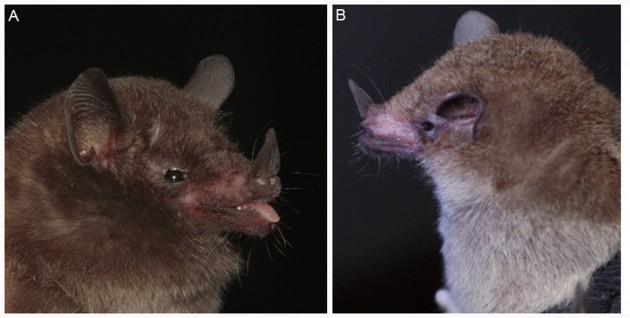

Two other bats that Ricardo Moratelli has recently helped classify as new species include “Lonchophylla peracchii” (left), and “L. bokermanni.” (Photo courtesy Ricardo Mortarelli)

Q: How important are museum collections in describing new species?

Moratelli: Often the first step in trying to understand relationships between species is to study museum collections like those found here in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. These collections allow us to look at specimens over a wide range of time periods and geographic areas, something that is nearly impossible to do by just doing fieldwork alone. The fieldwork I did in the border region between Brazil and Bolivia is a good example of this, as I spent two months trying to catch individuals of this new species of bat with no success.

New species are found in the drawers of museum collections all the time, especially now that we have access to new genetic techniques. There are specimens here at the Smithsonian that were collected more than 100 years ago that are just waiting to be described. And these are not just exceptional cases. Using the species I have already described as an example, the average shelf life between the first specimens collected and their formal descriptions is 62 years.

Q: Why is it important to describe new species?

Moratelli: Cataloging life on earth is the primary task of taxonomists like myself. We take the first step along the road of preserving a species by describing it. Generally when we describe a new species we know very little about its biology, so once taxonomists have described the species, ecologists can do the rest of the work trying to learn about the animal’s biology.