NASA’s next Small Explorer (SMEX) mission to study the little-understood lower levels of the sun’s atmosphere has been fully integrated and final testing is underway.

Scheduled to launch in April 2013, the Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) will make use of high-resolution images, data and advanced computer models to unravel how matter, light, and energy move from the sun’s 6,000 K (10,240 F / 5,727 C) surface to its million K (1.8 million F / 999,700 C) outer atmosphere, the corona. Such movement ultimately heats the sun’s atmosphere to temperatures much hotter than the surface, and also powers solar flares and coronal mass ejections, which can have societal and economic impacts on Earth.

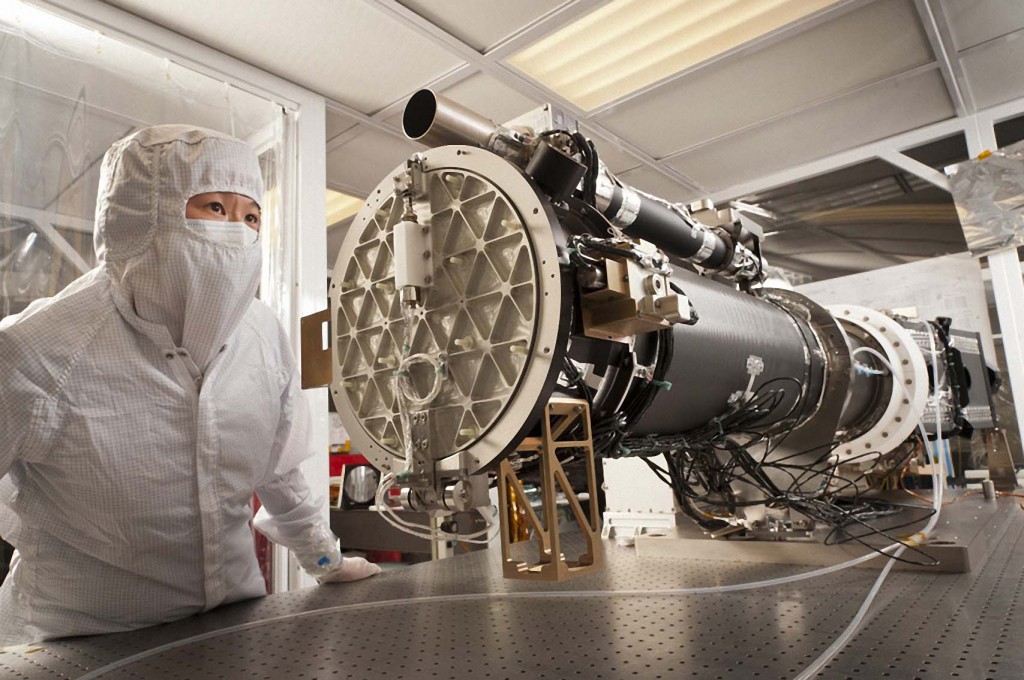

The fully integrated spacecraft and science instrument for NASA’s Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) mission is seen in a clean room at the Lockheed Martin Space Systems Sunnyvale, Calif. facility. The solar arrays are deployed in the configuration they will assume when in orbit. (Photos courtesy Lockheed Martin)

“This is the first time we’ll be directly observing this region since the 1970s,” says Joe Davila, IRIS project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. “We’re excited to bring this new set of observations to bear on the continued question of how the corona gets so hot.”

A fundamentally mysterious region that helps drive heat into the corona, the lower levels of the atmosphere — namely two layers called the chromosphere and the transition region — have been notoriously hard to study. IRIS will be able to tease apart what’s happening there better than ever before by providing observations to pinpoint physical forces at work near the surface of the sun.

Lockheed Martin Space Systems engineer Cathy Chou, integration and test lead for NASA’s Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) observatory, inspects the IRIS solar telescope in a clean room at the company’s Advanced Technology Center in Palo Alto, Calif.

IRIS was designed and built at the Lockheed Martin Space Systems ATC in Palo Alto, Calif., with support from the company’s Civil Space line of business and major partners the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and Montana State University. Ames is responsible for mission operations and the ground data system. The Norwegian Space Agency will provide the primary ground station at Svalbard, Norway, inside the Arctic Circle. The science data will be managed by the Joint Science Operations Center, run by Stanford and Lockheed Martin. Goddard oversees the SMEX program.

The mission carries a single instrument: an ultraviolet telescope combined with an imaging spectrograph that will both focus on the chromosphere and the transition region. The telescope will see about one percent of the sun at a time and resolve that image to show features on the sun as small as 150 miles (241.4 km) across. The instrument will capture a new image every five to ten seconds, and spectra about every one to two seconds. Spectra will cover temperatures from 4,500 K to 10,000,000 K (7,640 F/4,227 C to 18 million F/10 million C), with images covering temperatures from 4,500 K to 65,000 K (116,500 F/64,730 C).

These unique capabilities will be coupled with state of the art 3-D numerical modeling on supercomputers, such as Pleiades, housed at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif. Indeed, recent improvements in computer power to analyze the large amount of data is crucial to why IRIS will provide better information about the region than ever seen before.

The IRIS observatory will launch from Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif., and will fly in a sun-synchronous polar orbit for continuous solar observations during a two-year mission.–Source: NASA