By John Barrat

Some 1,500 to 1,000 years ago, the Chesapeake Bay region was dotted with the tiny settlements of prehistoric Indians who harvested the bay’s bounty of fish, shellfish and other animals. Today, numerous stone tools buried in sediments, shell middens and the outlines of their dwellings are all that remain of these little-known people.

As a coastal archaeologist and expert in prehistoric and historic settlement sites in the Chesapeake Bay region, Darrin Lowery of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and University of Delaware, is carefully watching the effects of coastal erosion and rising sea levels on coastal archaeological sites. As sea levels creep slowly upward, scores of these sites are slipping under water and becoming more difficult, if not impossible, to excavate and study.

Image right: Darrin Lowery examines soils and peat marsh for evidence of ancient landscapes and sea level rise on the Mockhorn Island in Virginia. (Photo by Mike Hardesty, Washington College)

Of equal concern, says Lowery, are the chemical processes that accompany rising seas, which can modify and deteriorate the stone tools that early Americans used to hunt and prepare food and clothing hundreds of years ago. Lowery is co-author of a recent paper in the Journal of Archaeological Science on the geochemical impacts to prehistoric artifacts in coastal zones. He recently answered a few questions about his work.

Q. How do the chemical processes of sea level rise affect primitive stone tools?

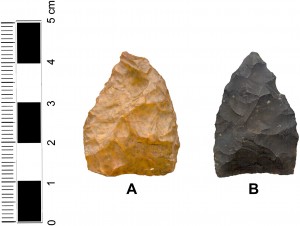

A. Slowly rising sea levels result in the regular input of sediment and organic matter into low-lying areas, essentially creating areas covered in tidal marsh. Sulfidization in a tidal marsh is a process that reduces iron to its ferrous state and produces pyrite, turning stone artifacts black. A prehistoric projectile point made of jasper that has been exposed to sulfidization looks like it is made of a different type of stone called chert. This is a challenge to archaeologists because it is generally assumed that broad lithic categories can be distinguished between stone tools that are made of either chert or jasper. Over time this process can change the look of a stone artifact both inside and out.

Image left: Jasper (A) and chert (B) projectile points found at eroding shoreline sites in the Middle Atlantic. (Images courtesy Darrin Lowery)

A second process common in salt marshes is sulfuricization, which creates sulfuric acid. Highly corrosive, this acid attacks the silicate structure of a stone tool, first staining the rock with a reddish brown color and eventually causing the artifact to decompose. Having these artifacts disappear from the historic record is also of great concern to archaeologists. For a museum curator, safely storing iron-rich stone tools or artifacts that have been exposed to acid sulfate is problematic.

Q. Is sea level rise the only culprit in these changes?

A. No. The widespread practice of dredging sediment from the bottom of estuaries or along the coast and using it to build up shorelines and create living coastlines and areas for housing developments can create a situation that results in a sulfuric-acid producing machine. Marine sediments that have been oxygen-starved for several millenia are dredged up, brought to the surface and exposed to oxygen. Aerobic bacteria working on the sulfates in the sediments create sulfuric acid, as well as a series of iron oxides. If the acid is dissolving silica in iron-rich prehistoric stone tools from archaeological sites on the coast, as I have witnessed, I can only imagine how it is impacting marine life in the area adjacent to the dredge spoils.

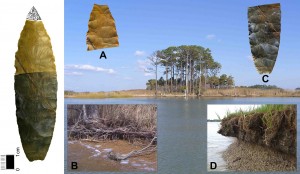

Image right: This freshly broken projectile point made of jasper reveals the gradual precipitation of pyrite into its core, a process that has dramatically changing its color.

Q. Can you determine how much sea levels have risen since prehistoric times in North America 1,000 years ago?

A. Humans don’t like to get their feet wet so we know that prehistoric coastal sites now underwater or buried in a tidal marsh were once terrestrial, and that people were once eating, sleeping and living on these spots. Because we know that some prehistoric settlement sites in the Chesapeake Bay area are situated beneath a meter of tidal marsh peat, we can use certain “known-age” iron-rich artifacts from these submerged coastal sites to assess rates of sea level rise, as well as the rates of acid sulfate chemical change. From this we can also gauge the accuracy of the reported sea level rise rates over the past few centuries.

Surveying a large number of drowned prehistoric sites gives us the opportunity to understand those rates and the reported magnitudes.

Q. Are your projects in the Chesapeake region only focused on prehistoric settlement sites?

A. With one of my research projects, I am trying to assess the reported historic rates of sea level rise using, in part, farm fields next to tidal marshes that were first plowed long ago. We have numerous detailed historic maps showing the topographically low tidal marsh areas around the Chesapeake Bay. These maps, which encompass the last 165 years, show many tilled upland hummocks surrounded by tidal marsh. Agriculturally mixed soils are a distinctive archaeological feature formed when the thin organic soil has been turned and thickened by the plow. Back in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, farmers in these low tidal marsh areas around the Chesapeake Bay didn’t have much land and they cleared every upland area right up to the edge of the marsh for cultivation. The 1840s and 1850s coastal survey maps clearly show the tilled field boundaries and historic structures on these upland hummocks.

Image left: The chemical processes that accompany rising seas is evident on the two halves of this jasper biface projectile point. The top of this artifact was found along the eroded forested upland (B). The bottom part (C) was altered by geochemical processes in the eroded upland area surrounded by tidal marsh (D) where it was found.

I’m geo-referencing these historic maps and overlaying them with recent satellite images to form a single comparative map. By doing this I can see the historic distribution of plowed fields and farms in these low coastal areas and compare them with today. Fieldwork in these areas has allowed me to relocate the historic plowed or tilled field boundaries. Many of the shorelines have been eroded by the effects of wind and waves. However, the historic plowed fields have not been inundated or covered by tidal marsh peat over the past 150 years.

What I’ve observed is that sea levels in the Chesapeake Bay may have come up a little bit in the last 150 years but I don’t believe they have risen as much as one foot, as some groups are reporting. In all my years of shoreline surveys I have never seen a 17th, 18th, or 19th century domestic site beneath a covering of tidal marsh peat. I think people are mistaking shoreline erosion and land loss, caused by wind and water chewing away at unconsolidated terrestrial sediments, with sea level rise.

For example, currently at Kent Narrows in the Chesapeake, a series of hummocks above sea level appear as upland landscapes with the same dimensions on the earlier 1840s coastal maps. Also on the Chesapeake’s Hoopers Island are a series of hummocks that were being tilled in the 1840s, the plowed landscape features are still there adjacent to the marsh and above sea level. I have observed the same conditions on Messongo Creek on Virginia’s eastern shore.

If sea levels had risen as much as one foot over the past century, the aerial extent of these isolated upland landforms should have shrunk in size and the historic plow zones associated with the hummocks should have been covered or partially covered by expanding tidal marsh.

It is important to remember that sediment erosion along shorelines does not equate to sea level rise and sediment accretion along shorelines does not equate to a sea level fall. As an example, Sharp’s Island at the mouth of the Choptank River consisted of more than 700 acres of land in 1847, but by the mid-1950’s the island had completely eroded away. Meanwhile, in 1849, Fisherman’s Island at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on Virginia’s eastern shore did not exist. Fisherman’s Island today consists of more than 1,800 acres of land and the island also has an extensive forested upland.