Nutmeg-loving toucans wearing GPS transmitters recently helped a team of scientists at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama address an age-old problem in plant ecology: accurately estimating seed dispersal. The tracking data revealed what scientists have long suspected, that toucans are excellent seed dispersers, particularly in the morning, and for the first time enabled researchers to create a map of the relative patterns and distances that toucans distribute the seeds of a nutmeg tree.

The reproductive success of any fruiting plant depends upon how effectively its seeds are dispersed yet tracking and mapping individual seeds carried off by the wind or ingested by animals is nearly impossible. Today, ecologists studying forest dynamics rely mostly on theoretical models to calculate the area of seed distribution for specific plants. New tracking technology however is changing that.

In the first stage of their experiment, the scientists collected fresh seeds from a common Panamanian nutmeg tree (Virola nobilis) and fed them to captive toucans (Ramphastos sulfuratus) at the Rotterdam Zoo. Toucans gulp nutmeg seeds whole, the outer pulp is processed in the bird’s crop, and the hard inner seed is then regurgitated. Five zoo toucans fed 100 nutmeg seeds took an average of 25.5 minutes to process and regurgitate the seeds.

A wild toucan in the rainforest at Gamboa, wearing a backpack containing a GPS transmitter and accelerometer. (Photo courtesy Roland Kays)

Next, in Panama, the scientists netted six wild toucans (four R. sulfuratus and two R. swainsonii) that were feeding from a large nutmeg tree in the rainforest at Gamboa. They fitted the birds with lightweight backpacks containing GPS tracking devices (these devices recorded the bird’s exact location every 15 minutes) and accelerometers which can measure a bird’s daily activity level.

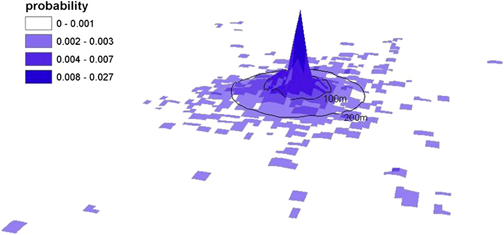

When matched with the seed-regurgitation time of the zoo toucans, the GPS data indicated the wild toucans were probably dropping nutmeg seeds a distance of 472 feet, on average, from the mother tree. Each seed had a 56 percent probability of being dropped at least 328 feet from its mother tree and an 18 percent chance of being dropped some 656 feet from the tree.

Researchers Reinhard Vohwinkel, left, and Martin Wikelski attach a high-tech backpack to a wild toucan. The backpacks are designed to fall off the birds after ten days. (Photo courtesy Roland Kays)

In addition, the accelerometer revealed that the toucans’ peak activity and movement was in the morning followed by a lull at midday, a secondary activity peak in the afternoon, and complete inactivity at night. This is a normal pattern of for tropical birds.

“Time of feeding had a strong influence on seed dispersal,” the scientists write. “Seeds ingested in morning (breakfast) and afternoon (dinner) were more likely to achieve significant dispersal than seeds ingested mid day (lunch).” This observation explains why tropical nutmegs are “early morning specialists” with fruits that typically ripen at early and mid-morning so they are quickly removed by birds.

Ideally, the scientists observed, nutmeg trees could increase their seed dispersal distances by producing fruit with gut-processing times of around 60 minutes.

![]() This spatially explicit map of the probability of see dispersal away from feeding trees by toucans shows seeds have a 56-percent chance of being dispersed more than 328 feet (100 meters) and an 18-percent chance of being moved more than 656 feet (200 meters).

This spatially explicit map of the probability of see dispersal away from feeding trees by toucans shows seeds have a 56-percent chance of being dispersed more than 328 feet (100 meters) and an 18-percent chance of being moved more than 656 feet (200 meters).

The article, “The effect of feeding time on dispersal of Virola seeds by toucans determined from GPS tracking and accelerometers,” was published in the journal Acta Oecologica. It was authored by Roland Kays of the New York State Museum and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute; Patrick Jansen of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and the Center fro Ecosystem Studies in Wageningen, The Netherlands; Elise Knecht of the Center for Ecosystem Studies, Wageningen; Reinhard Vohwinkel of Avifaunistische Untersuchungen, Germany; and Martin Wikelski of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, Germany. –John Barrat