Dr. Thomas R. Watters of the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum talks about his research in astronomy, particularly our moon.

You will not notice it when you look at the moon tonight, but it is actually shrinking. Smithsonian scientist Tom Watters made this discovery and he revealed this finding as the lead author in research published in the Aug. 20 issue of the journal Science.

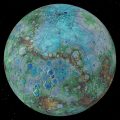

By looking at images and data taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, a team of scientists, including Watters, a planetary scientist in the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the National Air and Space Museum, were able to examine geological features on the moon called lobate scarps—thrust faults that occur primarily in the lunar highlands. These scarps are the result of the interior of the moon slowly cooling, and as it does so, it shrinks causing its surface area to crack and buckle.

“One of the remarkable aspects of the lunar scarps is their apparent young age,” said Watters. “Relatively young, globally distributed thrust faults show recent contraction of the whole moon, likely due to cooling of the lunar interior. The amount of contraction is estimated to be about 100 meters in the recent past.

The moon’s lobate scarps were first recognized in photographs taken near the moon’s equator by the panoramic cameras flown on the Apollo 15, 16 and 17 missions. Fourteen previously unknown lobate scarps have now been revealed in very high resolution images taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera. The newly detected scarps indicate that the thrust faults are globally distributed and not clustered near the moon’s equator.

“The ultrahigh resolution images from the Narrow Angle Cameras are changing our view of the moon,” said Mark Robinson of the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University, coauthor and principal investigator of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera. “We’ve not only detected many previously unknown lunar scarps, we’re seeing much greater detail on the scarps identified in the Apollo photographs.”

Because the size change is relatively small, however, Watters said that there would be no effect on lunar cycles, tides, etc. It would take millions of years for there to be a perceivable difference in the size of the moon to the naked eye. But this discovery does help change the commonly held belief that the moon is just a dead rock, showing that it is still active and dynamic.

The mare basalts that fill the Taurus-Littrow valley were thrust up by contractional forces to form the Lee-Lincoln fault scarp, just west of the Apollo 17 landing site (arrow). It is the only extraterrestrial fault scarp to be explored by humans (astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt). The digital terrain model derived from Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) stereo images shows the fault extending upslope into North Massif were highlands material are also thrust up. The fault cuts upslope and abruptly changes orientation and cuts along slope, forming a narrow bench. LROC images show boulders shed from North Massif that have rolled downhill and collected on the bench. Credit: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University