While society at large frets about plastics that pile up and seem to last forever— grocery bags clogging landfills and soda bottles washing up on beaches—museums worry about the thousands upon thousands of artifacts in their collections made of plastic, objects that in many cases are crumbling and cracking and sometimes damaging other artifacts as they break down.

“Plastic is a 20th-century material—it is everywhere,” says Jia-sun Tsang, a conservator at the Smithsonain’s Museum Conservation Institute. But most plastics—cheap to produce and adaptable to almost infinite uses—were not created for the ages. “When they get to a museum, it’s our problem. We have to take care of them.”

Photo: Jia-sun Tsang studies a set of 49 plastic samples from a 1920s Lumarith salesman’s kit in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. (Photo by Donald Hurlbert)

Typical plastic degradation was Tsang’s shorthand for the problem before her. The object of her concern, from the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Behring Center, was a salesman’s sample kit for a brand of plastic sold under the name Lumarith in the 1920s.

Easily melted and molded into virtually any shape, the product was popular with makers of everything from fountain pens and toys to electrical appliances. But with the passage of years, the kind of plastic used for Lumarith, cellulose acetate, broke down, giving off a telltale vinegar smell. Several of the brightly colored samples in the kit were warped, cracked, and unpresentable.

Tsang and a team of Smithsonian scientists used a variety of noninvasive analytical techniques, including several forms of spectroscopy to pinpoint the molecular structure of the plastic and figure out precisely the cause of the samples’ degradation. Tsang determined that much of the problem was due to leaching of triphenyl phosphate, a fire-retardant compound often added to cellulose acetate to facilitate its softening and flow during the molding process.

Tsang’s study concluded that triphenyl phosphate in cellulose acetate was a particular risk factor for plastic degradation, and that artifacts containing the chemical should not be stored in close contact or in an enclosed space with other cellulose acetate plastics and metals. Case closed, but the larger problem was far from settled.

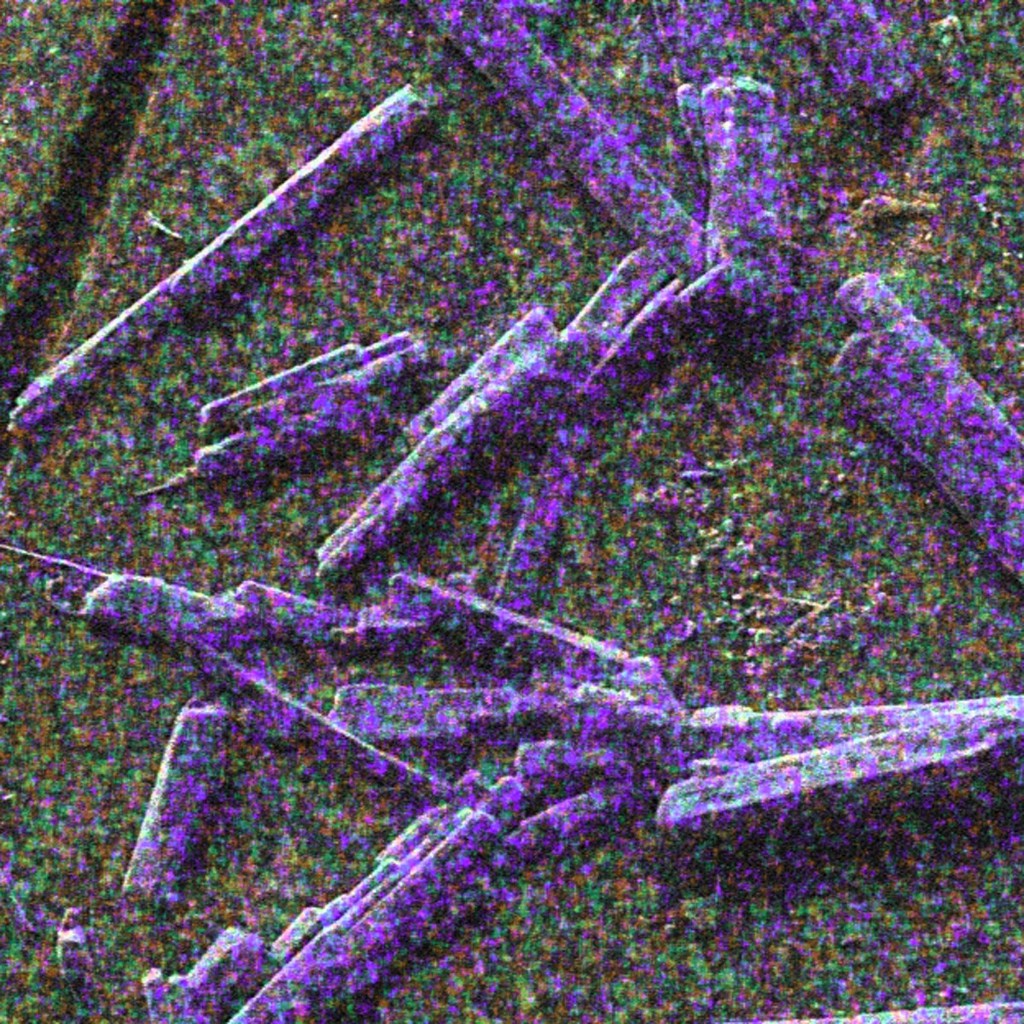

Photo: This scanning electron micrograph image of a Lumarith salesman’s sample shows fully formed corrosive crystals consisting of oxygen (orange), carbon (green) and phosphorus (purple), as well as a crack in the upper left.

A year-long survey at the American History Museum revealed that many plastics in its collections are from among the five types that museum conservators have identified as “malignant.” Not only are these problem plastics—cellulose nitrate, cellulose acetate, polyurethane, polyvinyl chloride and rubber—more prone to deterioration than other plastics but also their breakdown often produces gases that damage metal, paper or other plastics stored in their vicinity. In most cases, this harmful offgassing can’t be prevented, only slowed, which means degrading plastic artifacts must be isolated from other objects in museum collections.

Photo: Residue from a silicon breast implant stains a storage box at the National Museum of American History. (Photo courtesy National Museum of American History).

Tsang’s specialty is conserving modern paintings and other contemporary art, so a history museum might not seem like her usual haunt. However, before entering the field of fine-art conservation, she was a clinical chemist at the Medical College of Ohio. “Because of my background, I always like to get into the science,” she says. —Mike Lipske