By Grace Aldridge Foster

Men lean out the window of a school bus from Newark, N.J. as it arrives at Resurrection City, Washington, D.C. in 1968. Photograph by Robert Houston (National Museum of African American History and Culture collection)

The very first image at the exhibition’s entrance tells you this is not your average civil rights show—it’s in color. Photographed by Robert Houston, the large mural features a row of men leaning out the windows of a bright yellow school bus. Taped to the side of the bus is a sign that reads, “NEWARK NJ VAN-GUARD POOR PEOPLES CAMPAIGN.”

“City of Hope: Resurrection City & the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign,” remembers Martin Luther King Jr.’s final human rights crusade on its 50th anniversary. This new exhibition from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture opened in January at the National Museum of American History.

The show, which curator Aaron Bryant describes as a “visual culture exhibition,” is buzzing with vivid colors painted onto protest signs and tent panels and captured in photographs and video.

Night scene at a campfire at Resurrection City, Washington, D.C., 1968. Photograph by Robert Houston (National Museum of African American History and Culture collection)

“Generally, in civil rights exhibitions we’re accustomed to seeing photographs and media images in black and white,” explains Bryant, a curator of photography at the Museum of African American History and Culture. “What we’re doing…I think is pretty innovative.”

The effect is a show that feels current and alive, despite commemorating 50-year-old history. And indeed, that is part of the show’s mission—to inspire contemporary visitors and motivate them to act.

“History is as much about today and tomorrow as it is about yesterday,” Lonnie Bunch, founding director of the Museum of African American History and Culture, explained at the exhibition’s press opening. “And what I think museums do…is to help you remember, to remember these stories, to remember this history. Not out of nostalgia, but to give you a useful history. So in essence [the exhibition] is to inspire, it is to challenge, it is to remind us of what is possible.”

The Rev. Ralph David Abernathy and others during the Minister’s March at the Poor People’s Campaign in Washington, D.C. Photograph by Laura Jones. (National Museum of African American History and Culture photograph)

Bryant agrees. “How do we inspire activism? This exhibition is in part formed by that,” he says.

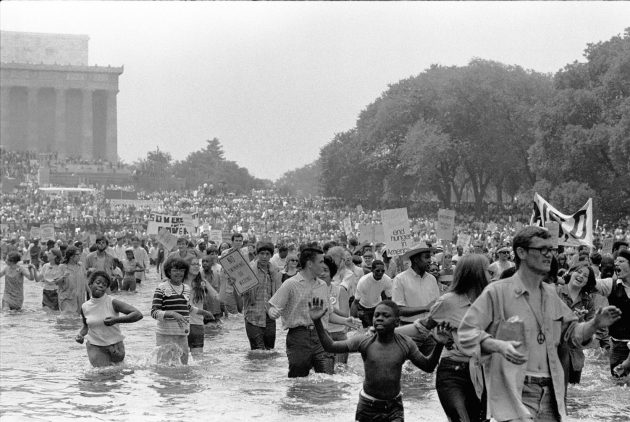

Located on 16 acres between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument, the real-life Resurrection City housed nearly 8,000 people who came to Washington, D.C., in 1968 from all over the country to occupy the National Mall for almost six weeks. The encampment was the heart and soul of a multiracial campaign to end poverty in the United States, led by civil rights giant Ralph Abernathy after King’s death.

Organizers centered the exhibition around Resurrection City for more than the obvious reason that it is the most well-known symbol of the Poor People’s Campaign.

People wade in the Reflecting Pool in front of the Lincoln Memorial during the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968. Photograph by Laura Jones (National Museum of African American History and Culture collection)

“More importantly,” Bryant says, “when looking at social movement–and this is something for activists who are working today to think about–social movements really rely on building a sense of community and a sense of culture. Those are two of the most important components of what keeps a social movement cohesive.”

At Resurrection City leaders of the movement planned programs to promote community engagement. They encouraged people to talk, to learn, to share information, and to sing. Engagement was also sparked by Resurrection City’s design.

Ken Jadin, one of the four architects who designed Resurrection City in 1968, says he and the other architects imagined U-shaped groups of four tents each so that people would face each other in their living quarters. But the people living there “were given the freedom to create the space they wanted,” Jadin said during the press opening. The architect recalls groups of kids who had never before built anything bringing materials and building livable two-story units.

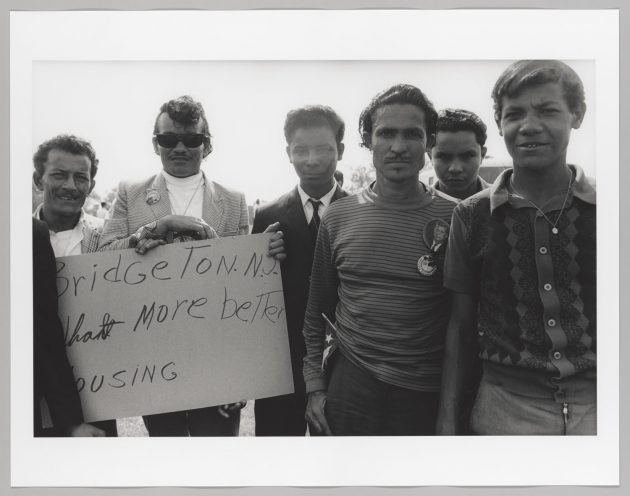

Six men advocate for more and better housing during the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968. Photograph by Jill Freedman. (National Museum of African American History and Culture collection.)

In addition to photographs and architectural plans, the exhibition showcases a tactile map of Resurrection City. The project team used photographs, maps, and film footage to create the display through a 3D printing process. Looking a little like a board game, the result is a captivating mosaic of small angular structures. According to Jaden, the team’s tactile rendering is “so much more orderly than my memory!”

At the end of “City of Hope” is a projected display juxtaposing three sets of video footage of Resurrection City taken from the top of the Washington monument. From that distance, the structures appear uniformly off-white. But vibrant protest signs and tent panels displayed in the show attest to the rainbow of colors represented on the ground. The show frames these objects as fine artworks, displaying them as if they are painted canvases. Bryant explains that this is all to reinforce the importance of visual culture to the Poor People’s Campaign and to the civil rights movement.

A round 1968 pinback button featuring a black and white portrait of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Printed by the AFL-CIO Locale 64 Union for the Poor Peoples Campaign. (Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture collection)

But our intention is also “to engage people in visual literacy,” Bryant says. “It’s not just about accepting things and walking blindly by, but to actually study and think about what you’re looking at and listening to.”

“This show isn’t about pointing fingers, shame, pity, guilt, or judgment,” Bryant continues. “It’s about presenting the history because we think the history, the photographs, the protest signs, the music, everything speaks for itself.”

Along with newly discovered film and audio footage and a number of never-before-displayed photographs, the show contains other media elements designed to viscerally share the experience of the Poor People’s Campaign.

Young girls in a tent doorway in Resurrection City, Wash., D.C., 1968. Photograph by Robert Houston. (National Museum of African American History and Culture collection)

A back-lit map of the United States uses colored lights to show the routes that caravans of people took from all over the country to travel to Washington, D.C. A huge wall-projected media display looks like something you’d find in a modern art museum; as the sound of rain plays in the background, life-size images of Resurrection City residents sloshing through deep mud move across the walls. A selection of oral histories is also nearby, one of several ongoing projects associated with the show.

Many of these media elements can be found in the exhibition’s online component, which will continue to expand over the life span of the exhibition, Bryant points out. “City of Hope: Resurrection City & the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign” is on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History through January 2019.