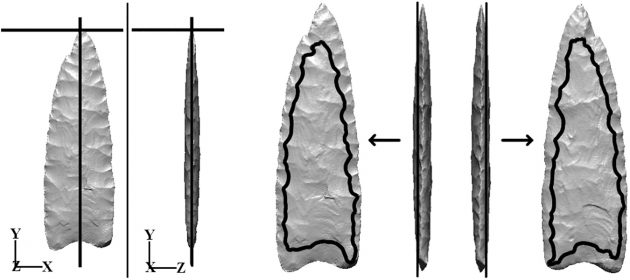

This figure shows one analysis used to study shapes left behind from their production on either side of the projectile points. (Image courtesy Sebastian Wärmländer, Stockholm University)

In a new study in which one of humankind’s most high-tech tools was used to analyze one of its most primitive, scientists have uncovered evidence of increased social isolation some 12,500 years ago among tribes of hunter-gatherers in North America. Using lasers to scan 50 authentic and replicated North American Clovis stone spear points, the team carefully documented how the point surfaces had been shaped as flakes of stone were chipped away. A computer 3-D model was made of each stone point and its contours carefully analyzed, measuring and comparing subtle surface features that cannot be discerned by eye.

The stone points revealed evidence of a shift toward more experimentation in production beginning about 12,500 years ago, following hundreds of years of consistent stone-tool production created using uniform techniques. The findings provide clues to a decrease in social interactions during a time when people are thought to have been spreading into new parts of North America and adapting to different environments, beginning a new period of cultural diversification.

This video was created by Dr. Sabrina Sholts of the Human Evolution Research Center at the University of California in Berkeley using 3D digital scans of a Clovis stone projectile point from the collections of the Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

The variability suggests that individual toolmakers, who may have had fewer opportunities than their predecessors to learn from others, began working out how to make the tools on their own. The findings, reported July 12 in the journal PLOS ONE, suggest a decrease in social learning and possibly a reduction in overall interactions among North American populations, the researchers say. This is consistent with anthropologists’ current thinking about how people were living during this time 12,500 years ago.

The research was led by Sabrina Sholts, curator in the Department of Anthropology at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, and Sebastian Wärmländer at Stockholm University.

Highly mobile hunter-gatherers of the Clovis culture spread quickly across North America, and Clovis points have been found all over the continent. Laser scanning their stone points is “a way to capture all the individual actions to reduce the core, which reflects the technique used to shape it,” Sholts explains.

“Our study really allows stone tools to speak in a new way,” says Joseph Gingerich, a research associate at the Smithsonian and assistant professor of anthropology at Ohio University. “By being able to document subtle changes in stone tool technology, we can better understand how social interactions among artisans changed in North America over 12,000 years ago.”

This figure shows a second analysis used to study shapes left behind from their production on either side of the projectile points. (Image courtesy Sebastian Wärmländer, Stockholm University)

The earliest well-documented group of people in North America, known as Clovis, is recognized by distinctive pointed stone projectiles that appear about 13,500 years ago. These culture-defining tools, called Clovis points, are sharp-edged and symmetrical, with a groove near the base—called a flute—where a spear shaft may have fit. Anthropologists consider them to be a very sophisticated technology.

Analysis revealed remarkable consistency among the ancient artifacts compared to almost perfect copies made by a modern knapper, an artisan that crafts stone tools using ancient techniques. The team concluded that the manufacturing technique used by the Clovis people was so uniform that it must have been passed on directly from one knapper to another.

According to the archaeological record, Clovis technology was used for several hundred years. A variety of other styles emerged later, though they never spread across the continent like Clovis points did. To learn more about the groups that manufactured these later styles, the authors of the study analyzed the surface features of 100 projectile points from collections at several museums, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History collection, which is curated by anthropologist Dennis Stanford.

This figure shows an analysis used to study shapes left behind from their production on either side of the projectile points. (Image courtesy Sebastian Wärmländer, Stockholm University)

The new study included Clovis points and samples of four later styles of fluted points, which had been recovered from sites in the eastern United States. The team analyzed the points’ surface contours as they had done in the earlier study and also introduced a new method of analyzing digital models to assess the objects’ 3D asymmetry.

Using a second new technique developed by Wärmländer and co-author Stefan Schlager of the University of Freiburg, the team determined that the overall 3D shapes of the points did not vary significantly. However, they did find increased variability in the surface contours among some of the later styles of points, indicating that those tools had not been produced using a consistent technique.

“There seems to be evidence of increased experimentation during this period, due to groups moving away from each other and pushing into new environments,” Sholts said.

“For a long time in North America, the archaeological record shows both consistency in stone tool technology and other aspects of culture,” Gingerich said. “In documenting a change in stone tool technology, we likely document the start of greater regional adaptations among some of the first hunter-gatherers in North America.”

This research was supported by the Smithsonian’s Small Grants Program.