By John Barrat

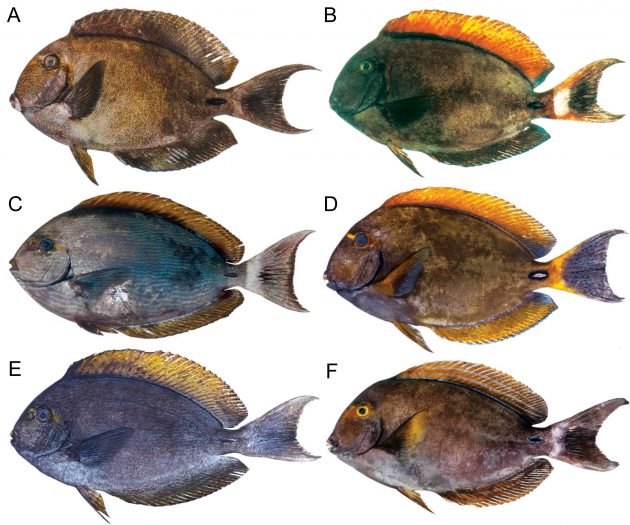

Six specimens of the new surgeonfish species “Acanthurus albimento” (above) were collected in northeastern Luzon during fish market surveys in the Philippines. Based on the sampling history in the region, the new species may be a limited-range endemic in the westernmost Pacific Ocean, which is unusual for members of this genus. (All photos by Jeff Williams)

Sometimes there’s just no telling what will turn up at the local market.

Fish biologist Jeff Williams of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and colleagues were stunned recently to find a large and vibrantly colored new species of surgeonfish being sold at fish markets in the northeastern Philippines. Surgeonfish, particularly of the genus Acanthurus to which this one belongs, have been closely studied and collected in the Philippines by scientists for decades. They have a distinctive appearance and are well-known there.

Sporting a prominent white band under its chin and having a vibrant orange head marked by wavy lines of iridescent blue, the improbable appearance of this distinctive new fish begs an explanation, so write Williams, Kent Carpenter of Old Dominion University and Mudjekeewis Santos of the Philippine National Fisheries Research and Development Institute. They are co-authors of a recent paper in the Journal of the Ocean Science Foundation that describes the fish, which they named Acanthurus albimento, meaning white (albus) chin (mento).

Insider talked with Williams about this discovery.

From left, Mudjekeewis Santos of the Philippine National Fisheries Research and Development Institute, Jeff Williams of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and Kent Carpenter of Old Dominion University peruse fish on sale in a Philippine fish market in 2014. (Photo courtesy Jeff Williams)

What were your thoughts when you first saw A. albimento?

Williams: Seeing them lying on a table in an outdoor market, I thought “Hey, what is that? Whoa, that’s not a described species.” We know the surgeonfishes very well and it was obvious immediately that this was something that had never been seen before.

Surgeonfish have been studied extensively around the world. Their highest diversity is in the Indo-Pacific. Huge numbers of species are described, their distributions have been documented, and they live out in the open, are easily caught, and are eaten in many Southeast Asian countries. In the Philippines, in particular, surgeonfish have been extensively studied over the past 100 years, so it was a bit surprising to find several specimens of this charismatic megafauna that were new to science.

Do you spend a lot of time at fish markets in the Philippines?

Williams: Yes. I’ve been collaborating on a project with Jon Deeds of the Food and Drug Administration for 10 years now to build a database library of mtDNA barcodes of all species of fish in the world: poisonous, commercial and noncommercial. The FDA plans to use it to identify fillets and other fish products being imported into the United States that cannot be identified taxonomically. This will prevent fraudulent importing of fish, and marketing of relabeled fish.

“Acanthurus albimento” is a new surgeonfish from northeastern Luzon described from six specimens collected during fish market surveys in the Philippines. The new species is characterized by a distinctive white band below the lower jaw; many irregular, wavy, thin, blue lines on the head; a brown-orange pectoral fin with a bluish tinge on the outer membrane of the rays and a dark band on the posterior margin; a narrow rust-orange stripe along the base of the dorsal fin; and a large blackish caudal spine and sheath with the socket broadly edged in black.

This project really took off after a shipment of what was called monkfish came to markets in Chicago. A couple skinned and made a stew out of a few of these things and, after eating the fish, they ended up in the hospital. It turned out they had tetrodotoxin poisoning. They had eaten pufferfish, the whole family of which is highly regulated for import because they have varying levels of poison in their flesh depending on the species and genus.

My Food and Drug Administration contact here in D.C. sent a picture to me and I knew right away just based on the skin that it was a pufferfish. The world expert on puffer fish, Keiichi Matsuura, just happened to be visiting the museum and staying at my home at the time. I took the picture to him and based on the spinule pattern on its back, he identified it as one of the most poisonous pufferfishes in the world.

The people survived and the shipment was halted.

Why the Philippines?

Williams: The Philippines has the highest diversity of fish in their markets anywhere in the world so we go there to collect every species. We visit a combination of markets, landings where fishermen bring their boats in and off-load their catch, and roadside stands. We go at peak landing times and each time a species is encountered that has not been collected before, we purchase three for processing. We check through hundreds of small tables of fish in the local stalls. So far we’ve found 1,300 species that they eat. The number goes up every trip.

While our surveys have yielded many new species, A. albimento is an easily distinguishable, large [about 10-12 inches long] surgeonfish.

“Acanthurus albimento” (image A above) is described as a new surgeonfish from northeastern Luzon from six specimens collected during extensive fish market surveys in the Philippines. An analysis using the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI), supported by an independent multi-locus analysis, suggests phylogenetic affinities with an “Acanthurus” clade that includes “A. auranticavus,” “A. bariene” (image B above), “A. blochii” (Image C), “A. dussumieri” (Image D), “A. gahhm,” “A. leucocheilus,” “A. maculiceps, “A. mata” (Image E), “A. nigricauda,” and “A. xanthopterus” (Image F). This clade shares a suite of color characteristics.

How are the fish caught?

Williams: By every conceivable method you can imagine: by spear, with block-nets that the fish are chased into, trawling, hook and line, drift nets, hand nets. Surgeonfishes are caught up above the reefs and rocky areas.

How are they cooked?

Williams: Often people gut them and fry them in a pan and cook them mostly whole. They sometimes make them into fish and vegetable dishes. Fish are an extremely important part of the diet in the Philippines and there are lots of different preparations.

In the markets, the fish are very fresh and are often sold within hours of being caught. There is no refrigeration, no air conditioning, and no ice. It is hot and the fish are lying out on concrete tables in covered open-air areas.

What does A. albimento taste like?

Williams: I actually don’t like to eat fish. I study fish, I don’t usually eat them. It makes it much easier to preserve a fish if you are not desperate to put it in a pan.

From left, Mudjekeewis Santos of the Philippine National Fisheries Research and Development Institute, Jeff Williams of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, Kent Carpenter of Old Dominion University, and Apollo Marco Lizano, a research assistant who has worked with Williams on several trips, peruse fish on sale in a Philippine fish market in 2011. (Photo courtesy Jeff Williams)

Why do you suppose this species was never collected before?

Williams: The northeastern area of the Philippines, on Luzon Island, where six A. albimento specimens were collected in three different markets, is relatively remote and gets hammered by typhoons constantly. It’s dead center on the typhoon target list. Huge numbers of typhoons go right across that northeastern quarter of Luzon. So, it’s not a common tourist destination for foreigners and not the easiest place to get to. It’s a beautiful part of the island but has not been sampled well over time.

In addition, we suspect these fish might be endemic to a small area in the Lamon Bay region. A circular eddy in the bay region may prevent its larvae from moving out into the Kuroshio Current and being dispersed northward up to Taiwan. If A. albimento were in Taiwan they certainly would have been collected before. Its life history remains unknown, but we hypothesize its larvae are caught in this eddy and they settle out right where they were spawned

Many scientists were surprised to see this fish and it has been suggested it may be a hybrid, but that is impossible as we have genetic data for nearly all surgeonfishes reported from the Philippines refuting this idea. The only species that could potentially be parents for a hybrid have never been observed in markets in the Philippines and were certainly not present in the markets where we found our specimens. This impossible idea never even occurred to the two scientists who reviewed the manuscript and one is the world’s expert on these fishes.

As we write in our paper, A. albimento’s discovery suggests further marine studies are warranted along the eastern seaboard of the Philippines and northeastern Luzon in particular.