By Michelle Z. Donahue

This image shows two Hopewell Havana meteoritic metal beads with a (1 cm/.39 inch) cube for scale. The bead on the left (.27 ounces/7.8 grams) is cut perpendicular to the central hole, illustrating the extensive alteration of the bead and infilling of the central hole. The bead on the right (.16 ounces/4.6 grams) is cut parallel to the central hole and exhibits a concentrically deformed structure. (Photo courtesy Tim McCoy)

To the Hopewell Culture, ancient Native Americans who sought out the exotic from near and far, metal was a rare and precious resource. Copper, found in its pure form or laboriously extracted from rock, was common, but they didn’t have the technology to smelt iron. So how and where did the Hopewell come by enough near-pure iron to produce a handful of exotic beads, small tools and other decorations?

In short: from space. A new study led by geologist Tim McCoy of the Mineral Sciences Department of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, traces a set of iron Hopewell beads to their source meteorite. Whether the Hopewell were the first to discover the prehistoric meteorite, or acquired it through interactions with other Native Americans is a subject of debate in anthropological circles. McCoy is lead author of the study published recently in the Journal of Archaeological Science, which adds to discussion on how the Hopewell may have obtained the metal.

In 1945 two dozen tube-shaped metal beads were found in Hopewell burial mounds in Havana, Ill. The Smithsonian now holds two of the beads in its National Meteorite Collection.

Smithsonian geologist Tim McCoy displays two pieces of an iron meteorite found in Minnesota and Wisconsin, which he recently determined were the source of two dozen Native American beads discovered in a 2,000-year-old burial site in Illinois. (Photo by Michelle Donahue)

The beads in particular drew McCoy’s interest because of his own Native American heritage: He is a member of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, whose ancestral territories covered parts of Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Wisconsin and Michigan.

“We think of metal today as being everywhere, but it was a fairly scarce commodity before 1492,” McCoy says. “So in archaeological digs from before Spanish contact, when you find something metallic, you start questioning how it got there.”

Widmanstatten

In the 1970s, the beads were identified as chemically and structurally similar to four raw meteorites in the Smithsonian collection, in part because of a distinctive crosshatch feature known as the Widmanstatten pattern. The crosshatching only becomes apparent when a meteorite is cut open and polished. One meteorite from Australia was eliminated due to its distant origin, leaving meteorites from Anoka, Minn.; Edmonton, Ky.; and Carleton, Texas as possible candidates for the beads’ source material.

A cross section of a meteorite found in Edmonton, Ky., shows a characteristic cross-hatched texture of iron meteorites, known as the Widmanstatten pattern. Along with in-depth chemical analysis, the unique pattern of cross-hatching in a meteorite found in Anoka, Minn., helped McCoy link that fragment with two dozen tube-shaped beads made of an iron meteorite found in Native American burial mounds in Havana, Ill. (Photo by Michelle Donahue)

“But nobody thought that the Havana beads had come from any of these three meteorites,” McCoy says. “Partly, because they’d all been buried, but also because there was no evidence that any of them had had anything removed or cut off of them.”

New scientific instruments that were not available to researchers even a decade ago, let alone when the major analysis of the Havana beads was done in the 1970s, allowed McCoy to closely compare both the beads with the Anoka, Minn., fragment. With virtually identical ratios of iron, nickel and phosphorous, very close matches in other trace elements, and fine-grained structural similarities, it’s unlikely the beads came from a source other than the Anoka meteorite.

“Sure, the Hopewell could have found and used an iron meteorite identical in composition to this one,” says McCoy, curator-in-charge of the museum’s meteorite collection. “But we have 1,000 iron meteorites from around the surface of the earth, and there aren’t many that match this. The easiest explanation is that we have an iron meteorite from the source region, and that it was the source of the Havana beads.”

Meteoritic metal bead formed from the Anoka iron using wood-fueled fire for heating and lithics for deformation. This image is a reflected light photomicrogaph of a cross section of the bead illustrating the deformation of the Widmanstatten pattern. Bead is 1 cm in exterior diameter. (Image courtesy Tim McCoy)

The original Anoka fragment was found in 1961. When a second, larger piece turned up just across the Mississippi River in Wisconsin in 1983, it suggested the parent meteorite broke up on its way through the atmosphere, and was strewn across the landscape in a “fall” of fragments.

This means more pieces could have been found during the intervening millennia. Analysis of rare gas isotopes, produced by cosmic rays while the meteor was still in space, suggest the original mass of the intact Anoka meteorite was in excess of 8,800 pounds (3,991.6 kilograms). The 1961 fragment weighed only 2.44 pounds (1.11 kilograms); the 1983 piece added another 198 pounds (89.8 kilograms).

River connection

One of the hallmarks of Hopewell culture is their seeming affinity for the foreign and the exotic. Hopewell sites have turned up fossilized shark teeth from the Gulf Coast, mica from the Appalachian Mountains, and obsidian and grizzly bear teeth from the Yellowstone National Park area in Montana. Yet, as far as the archaeological record shows, the Hopewell people never lived in these places.

Map of find site of the Anoka iron meteorite in Anoka and Champlin, Minn., and the recovery site of the Havana meteoritic metal beads in Havana, Ill. These sites are connected via the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers. Also shown are Hopewell centers near modern-day Chillicothe, Ohio and Trempeleau, Wis. Modern state boundaries shown for reference. (Map courtesy of Tim McCoy)

Just as it is unclear how the Hopewell obtained these items from far away, how they acquired iron meteorites to make into beads is also a mystery. They could have sent travelers to collect such objects, or the iron pieces could have come to the Hopewell via a shadowy trade network. It could have also just been a chance find.

For the Havana beads, McCoy thinks it has something to do with rivers. Havana is on the Illinois River, a tributary of the Mississippi 500 miles downstream from where the Anoka meteorites were found.

“In the original analysis, no one really considered the connection of rivers between archaeological sites,” McCoy points out. “With an object this small, I find it hard to believe anybody would have launched an expedition from Havana to go up river and find an iron meteorite. I think there was a trade network.”

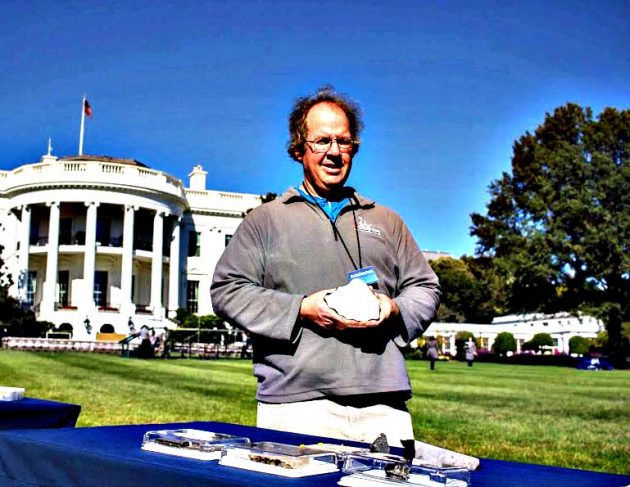

Smithsonian geologist and meteorite researcher Tim McCoy holds a sample of an iron meteorite at a White House Astronomy Night event in 2015. (Photo courtesy Tim McCoy)

What is certain, though, is that none of the Hopewell people ever acquired a very large piece of meteorite. Of the more than 100 Illinois-area Hopewell sites excavated in the last 150 years, only 5 ounces (160 grams) of iron artifacts have been found—about the weight of an average hockey puck. That includes the Havana beads. By contrast, just under 13 pounds (6 kilograms) of copper was found at a single burial site in Illinois in 2015.

Campfire metalworking

For the study, McCoy also demonstrated how early American Indians might have fashioned such beads some 2,100 years ago, by making one of his own with little more than a hot campfire, sticks and stones.

Three iron meteorite beads (right) found in Chillicothe, Ohio in the early 19th century, were linked to a meteorite from Brenham, Kan. (left), in the 1960s. The link between the Anoka, Minn., meteorite piece and beads made from meteoritic iron found in Havana, Ill., is only the second time an ancient Native American meteorite artifact has been linked to its parent meteorite. All are in the (Photo by Michelle Donahue)

The iron-nickel composition of these meteorites allows them to soften easily in the very hot coals of a wood fire, around 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit. On his brother’s farm in Illinois, McCoy used flat granite rocks to pound and shape a heated chunk of meteoritic metal into a bead that resembles an ancient one from Havana. An earlier experiment with modern metalworking tools resulted in a bead with a too-perfect surface, inspiring McCoy’s attempt with more historically accurate methods.

Many of the other Hopewell-era meteorite objects haven’t been examined with modern analytical tools, so this study could prompt further investigations of where their meteorite material came from, McCoy says. Knowing the iron’s origins may help clarify how and where the Hopewell people were sourcing their exotic goods.

By pounding a heated meteorite chunk with granite rocks Tim McCoy was able to create a rolled, tube-shaped bead similar to several dozen found buried at 2,000-year-old archaeological sites in Illinois and Ohio. (Photo courtesy Tim McCoy)

“The new study of Illinois Hopewell iron beads is thought-provoking work that will definitely open new avenues for understanding trade in prehistoric North America,” says Ken Farnsworth, an archaeologist with the Illinois State Archaeological Survey and a Hopewell expert.

“Since these 2000-year-old societies left no written records, only archaeology can tell us who they are and how they lived. Hopewell people used a lot of copper for special tools and decorations but they used very little iron—it’s known only from three burials—and we haven’t known where they got it,” Farnsworth says. To identify artifacts with known meteorites may tell us where the iron came from and how far it had to be traded to end up among Illinois people.”