By Evan Berkowitz

In a pleasant purple room just past a portrait of Pocahontas, some of the National Portrait Gallery’s youngest visitors are conducting what Albert Einstein once called “the highest form of research.”

“When children play, they develop cognitive, emotional, social and physical skills,” says Rhonda Buckley-Bishop, president and CEO of the Explore! Children’s Museum, which is coming to Washington, D.C. in 2019.

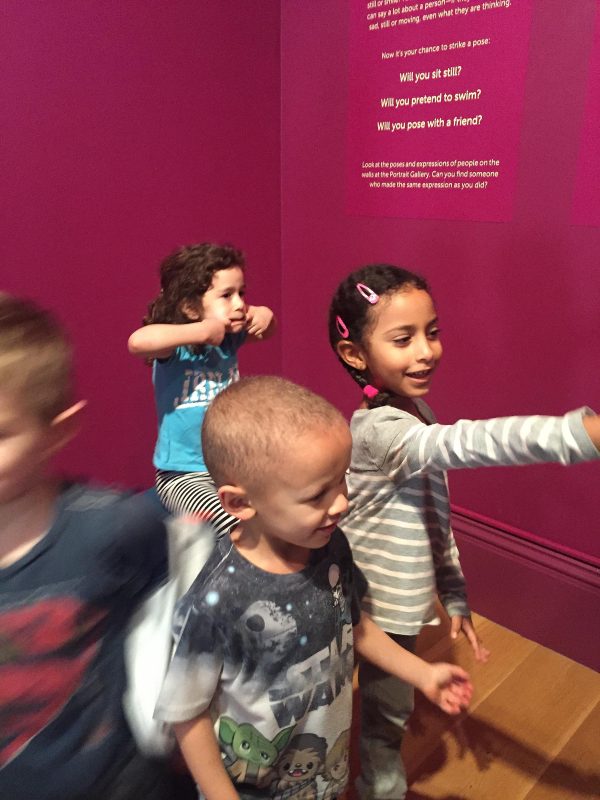

In a section of the new children’s space at the Portrait Gallery, “Strike a Pose,” children act out different portrait poses. (National Portrait Gallery photo)

In this newly opened children’s space, the National Portrait Gallery joined with the Explore! Children’s Museum to create a learning destination for visitors so young that the Portrait Gallery had never quite catered to them before.

“Explore! With the National Portrait Gallery,” a bilingual, wheelchair-accessible space, is open Tuesdays through Sundays from 11:30 a.m. to 6 p.m.; it features five learning stations and two original artworks that symbolize its ideals.

From building blocks that shuffle facial features to a photo booth that allows children to “Strike a Pose” and end up on a photo wall, “Explore! With the National Portrait Gallery” challenges kids age 18 months to eight years to explore what portraiture truly is.

“This space will help younger people think about who they are and the face they put on for the world,” Kim Sajet, Portrait Gallery director, says. “We hope that they’ll leave this space and look around at the rest of the museum and realize that looking at people is kind of fun. You learn a lot and it’s a window into achievement of all types.”

Identity is a core theme of the new children’s space, Rebecca Kasemeyer, NPG’s associate director of education and visitor experience, says.

A young boy uses a magnetic image of a hat to top a portrait of he created in the Portrait Gallery’s new children’s space “Explore!” (National Portrait Gallery image)

“The biggest piece is identity, how we see ourselves and how others see us,” she explains. “The beauty of portraits, at least the way we use them, is very much about what we see.”

Deconstructing everything from a subject’s clothes and possessions to their gaze and expression can help viewers make inferences about a portrait.

“When I talk about portraits, I ask people to look at the gaze,” Sajet says. “When someone looks directly at you, they’re almost having a conversation. If someone’s looking off in the distance, the viewer becomes sort-of a voyeur. That gets interesting when you start talking about human relationships.”

The Portrait Gallery hopes to foster an understanding of portraiture at a young age.

“As a mother, I’d like to think that my kids got used to looking closely at people,” Sajet says. “To be able to identify how people are grabs this sense of empathy within them.”

Buckley-Bishop agrees. “When they look at each other, they can see similarities, and they can also celebrate differences. We hope that this space will propel children toward having an ability to live with compassion, with purpose and empathy.”

A young visitor to the Portrait Gallery’s newly open children’s space plays with building blocks that can be arranged to create a variety of different portraits. (National Portrait Gallery Image)

Kasemeyer hopes children will be able to foster this empathy by exploring the artist-sitter relationships in the activity “Strike a Pose,” and in the silhouette station where one child draw’s another’s profile on a light board.

For the youngest visitors, building blocks and a mirror and felt boards peppered with facial features can be rearranged to create a seemingly infinite array of portrait combinations.

“This station is really the idea of not only seeing yourself but seeing others,” Kasemeyer says. “By creating different faces with the magnets and the felt pieces [children are] really thinking about how you see yourself and how other people see you.”

But the space goes beyond appearance.

A young lad creates ‘portraits’ on a blank board using magnets depicting different articles of clothing and facial features. (National Portrait Gallery image)

“Ironically, as you can imagine for a portrait gallery, it’s not what you look like that matters; it’s what you do in life,” Sajet says.

“The Portrait Gallery is very much about the biography and the individuals and their accomplishments,” Kasemeyer adds. The quiet respite of a book nook permits parents and others to begin this process through reading aloud to children about subjects in the Portrait Gallery.

Two original artworks chosen for the space also serve to arouse curiosity in children.

One painting, of an early Smithsonian regent and his family, explores the idea of education and brings children’s portraits into a children’s space. The other depicts Jane Bolin, a prominent childhood education activist and the country’s first African American female judge.

Information on Bolin is purposefully excised, with the hope it will start conversations with museum staff.

“The beauty of this space is that it is a work in progress,” Kasemeyer adds.

“We’re learning a lot,” Sajet says. “We are interested to see how popular this will be.”

Museums serve the entire life cycle, Sajet observes, but previously the Portrait Gallery’s programming tended to begin around age nine.

“We’ve always felt that we missed the very young,” she says. “We get a lot of families that’ll run through the water in the Kogod Courtyard. This new space gives them something portraiture related that they can actually do.”

“I’m super excited to be able tell families when they come in, ‘We have a space for you,’” Sajet concludes. “‘Here’s somewhere you can come in and it’s OK to touch and it’s OK to play.’”