By Grace Aldridge Foster

Marlene Dietrich in “Dishonored” (detail) by Eugene Robert Richee. Photo blow-up 1930. (Photograph by Eugene Robert Richee, Deutsche Kinemathek – Marlene Dietrich Collection Berlin)

Marlene Dietrich, early darling of the silver screen, was curating an Instagram-perfect image for herself 80 years before Instagram was invented.

Although Dietrich’s photographs might have made her “Insta-famous” if social media and the Internet had been around in the 1920s, she was not instantly famous. The now-iconic actress, known for her striking features and bold androgyny, had to pay her dues like any other Hollywood newcomer.

In a new National Portrait Gallery exhibition, “Marlene Dietrich: Dressed for the Image,” a photograph of a young Dietrich—holding a suitcase while wearing an under-slip—hangs on the wall. Her early gigs as a model were by no means glamorous.

“I wanted to tell a story,” says historian Kate Clarke Lemay, who curated the exhibit. “In the first section, I chose images that display Dietrich achieving life milestones like education, marriage, and having a child.”

Witness Dietrich as a precocious and athletic child, and Dietrich as a young bride. Later, Dietrich as a young silent-film actress, live performer and model.

“She was photographed in her early days, a lot,” Lemay adds. “She was kind of an every-woman, until she suddenly wasn’t.”

The exhibition presents a woman who wrote her own rulebook and adhered strictly to her own moral compass, shaped by her Prussian upbringing in post-World War I Germany. Its story offers a new angle, too, arguing that Dietrich fastidiously fashioned and controlled her own image. “I dress for the image. Not for myself, not for the public, not for fashion, not for men,” she once said.

After extensive archival work at the Deutsche Kinemathek, Germany’s National Museum of Film in Berlin, and two years of preparation, Lemay crafted a narrative of Dietrich’s dogged efforts to control her own image. Early in her career, Dietrich became a master of lighting, angles and the sultry stare.

Marlene Dietrich by George Hurrell, Photo blow-up, 1937. (Courtesy Michael Hadley Epstein and Scott Edward Schwimer, © HurrellPhotos.com)

Her intelligence—the “sense of a brain behind her gaze”—is one of the reasons Lemay chose Dietrich as the subject of a National Portrait Gallery exhibition.

Smart enough to know she wasn’t the smartest person in the room, Lemay says, Dietrich always picked out the person who was.

Josef von Sternberg was one such person. Sternberg directed Dietrich’s first six films produced by Paramount Studios, and the two became lovers. Though Dietrich was married at 21 to Rudolf Sieber, the couple maintained an open marriage, and Dietrich had many lovers, both men and women, over the years.

It was from Sternberg that Dietrich learned all about lighting—a knowledge she employed in fashioning her public image.

In one of the most striking photographs in the exhibition, Dietrich sits in a chair, legs crossed, with a photographer working a camera right behind her. She stares straight ahead into a floor length mirror.

“She’s so in control,” says Lemay, for whom this image is a favorite.

After her partnership with Sternberg ended, Dietrich continued to use and improve upon the lighting techniques she learned from him. She is nearly always lit from above in her portraits, and she often viewed and rearranged herself in a mirror before allowing herself to be photographed.

This image of Dietrich looking into the mirror evokes the modern-day “mirror selfie,” beloved by fashion bloggers, reality TV celebrities and teenagers everywhere.

It’s the timeliness that caught the attention of Kim Sajet, National Portrait Gallery director, who expanded the scope of the exhibition from its initial plan.

Dietrich in Seven Sinners by John Engstead, 1940 (photo courtesy of Deutsche Kinemathek – Marlene Dietrich Collection Berlin)

Contemporary conversations about gender fluidity, ageism and immigration have primed a wide audience to recognize Dietrich’s significance.

“Kim knew we were having a moment [in the culture] and we needed to seize it,” Lemay says.

Dietrich’s appeal is multi-faceted, and the exhibition explores many angles of the person through portraits. Dietrich, whose allure made kissing a woman on screen palatable to early 20th-century audiences, delights and intrigues on multiple, complex levels: a Hollywood star, singer, fashion icon, lesbian icon and more. She remains an influential figure of the LGBTQ community.

![]() Lemay, who holds a dual Ph.D. in art history and American studies, is most intrigued by the time Dietrich spent entertaining American troops in Europe during World War II.

Lemay, who holds a dual Ph.D. in art history and American studies, is most intrigued by the time Dietrich spent entertaining American troops in Europe during World War II.

Marlene Dietrich Broadcasting with Army [copy 1] by Unidentified Artist. Gelatin silver print, May 1944 (Deutsche Kinemathek – Marlene Dietrich Collection Berlin)

In one photograph, a sequin-clad Dietrich dazzles a crowd of uniformed soldiers. Lemay points out their muddy boots and heavy coats. They all carry guns.

“These guys were just behind the front lines…and they’re scared to death. They’re fighting in this terrible war, but they’ve got this great actor in front of them and you can see how lightened their mood was,” Lemay says.

Dietrich was ultimately awarded the Medal of Freedom for her service and remains a symbol of anti-Nazism.

Marlene Dietrich by Milton Greene. Archival inkjet 1952 (printed 2017) (Photographed by Milton H. Greene, ©2017 Joshua Greene, www.archiveimages.com)

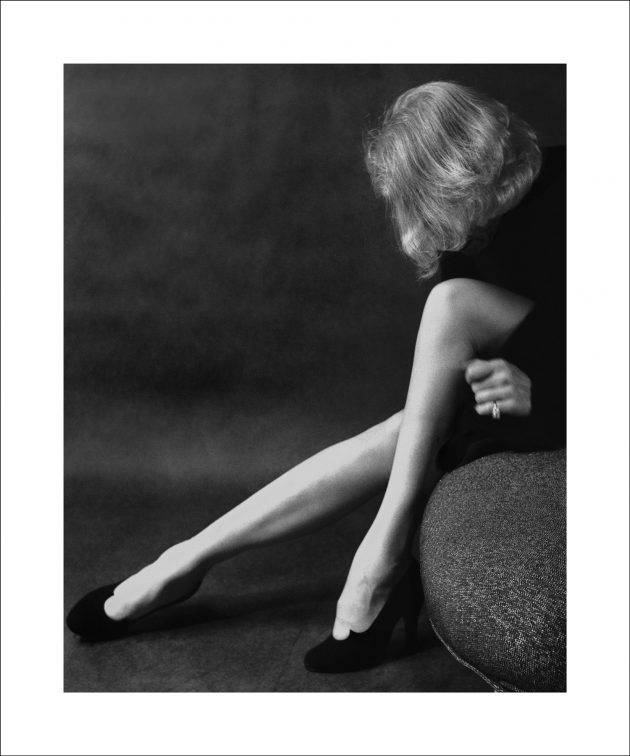

As she grew older, Dietrich vanished from the public eye. Unable to control her image as she wished, she chose to hide it. In the final photograph of the show, an aging Dietrich leans over her long, slim legs and allows her hair to cover her face. It is the only image in the exhibition that does not show Dietrich’s face.

“I thought that would be a good way to close the show,” says Lemay. “She worked so hard on her image, and I wanted to respect that.”

“Marlene Dietrich: Dressed for the Image,”—the first exhibition in the United States to examine Dietrich’s life and career—is on view at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery through April 15, 2018.