By Katie Neal

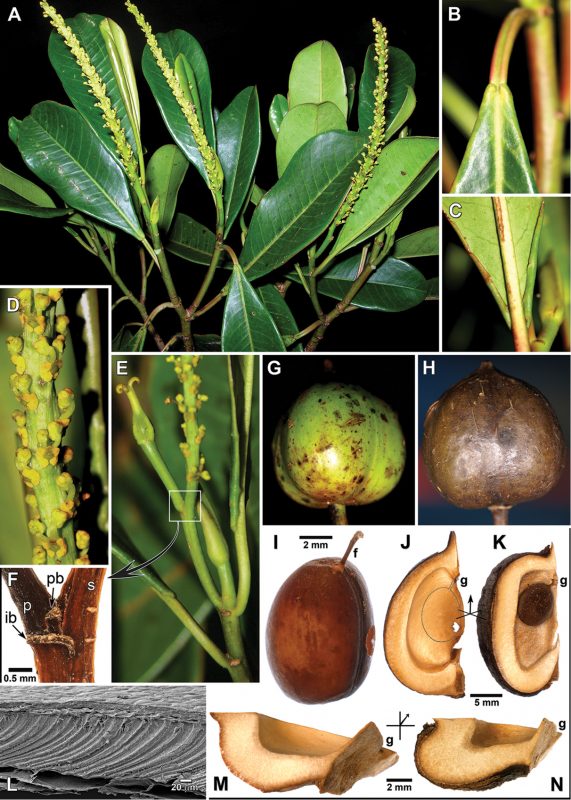

Fruit and leaves of “Incadendron esseri” (Photo by Jason Houston)

Hidden in plain sight–that’s how researchers describe their discovery of a new genus of large forest tree commonly found, yet previously scientifically unknown, in the tropical Andes.

Botanist Kenneth Wurdack from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and Wake Forest University graduate student William Farfan-Rios detailed their findings in a study just released in the journal PhytoKeys.

Named Incadendron esseri (literally “Esser’s tree of the Inca”), the tree is a new genus and species commonly found along an ancient Inca path in Peru, the Trocha Unión. Its association with the land of the Inca empire inspired its scientific name.

So how could a canopy tree stretching up to 100 feet tall and spanning nearly two feet in diameter go undetected until now?

Incadendron is known from three well-separated clusters of localities– Cóndor, Manu (shown here), and Oxapampa–on the eastern slopes of the main Andean mountain range in Peru and Ecuador, where it occurs in wet montane forests at elevations of 1,800–2,400 meters. The extent of its range is unclear due to the floristically poorly known nature of the intervening areas, and it should be looked for in similar habitats between the three populations.

“This tree perplexed researchers for several years before being named as new. It just goes to show that so much biodiversity is unknown and that obvious new species are awaiting discovery everywhere–in remote ecological plots, as well as in our own backyards,” says Kenneth Wurdack, a botanist with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

“Incadendron tells us a lot about how little we understand life on our planet. Here is a tree that ranges from southern Peru to Ecuador, that is abundant on the landscape, and yet it was unknown,” Miles Silman, the Andrew Sabin Family Foundation Presidential Chair in Conservation Biology at Wake Forest, says. “Finding this tree isn’t like finding another species of oak or another species of hickory—it’s like finding oak or hickory in the first place.”

The morphology of “Incadendron” is displayed in images A–J and L–M. Images K and N are from a different species, “Senefelderopsis croizatii”

The tree belongs to the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae – best known for rubber trees, cassava, and poinsettias – and like many of its relatives, when damaged also bleeds white sap, known as latex, that serves to protect it from insects and diseases.

Its ecological success in a difficult environment suggests more study is needed to find the hidden secrets that are often inherent in newly discovered and poorly known biodiversity.

Currently Incadendron is common in several research plots under intensive study as part of the Andes Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research Group, an international Andes-to-Amazon ecology program co-founded by Silman.

“While Incadendron has a broad range along the Andes, it is susceptible to climate change because it lives in a narrow band of temperatures. As temperatures rise, the tree populations have to move up to cooler temperatures,” Silman explains.

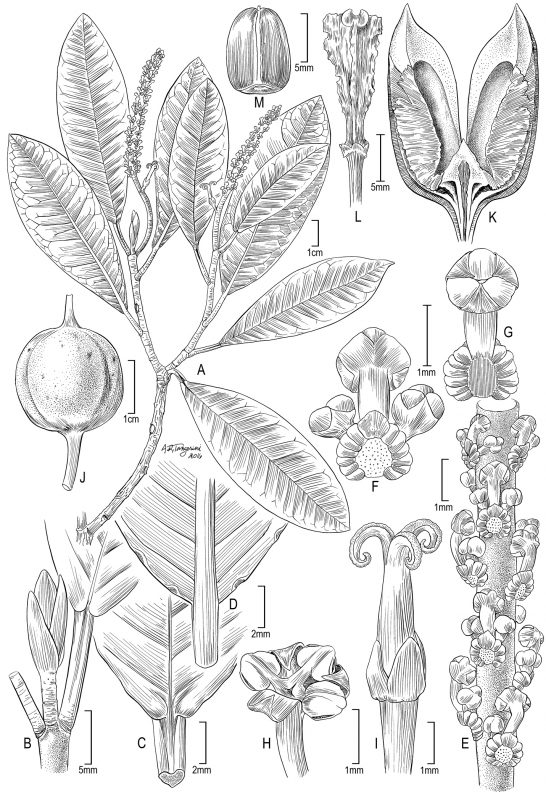

Illustration of “Incadendron esseri.” A Habit B Shoot tip C Leaf base (adaxial) D Leaf base and marginal glands (abaxial). E Staminate subinflorescence F Staminate cymule (distal view) G Staminate cymule (proximal view, without lateral buds) H Staminate flower I Pistillate flower J Fruit K Mericarp valve L Columella M Seed (ventral face).

For co author Farfan-Rios, who has been researching tropical forest dynamics and responses to changing environments along the Andes-to-Amazon elevational gradient, the discovery of Incadendron hits particularly close to home. Farfan-Rios is a native of Cusco, Peru. Not only is the new genus vulnerable to climate change, but it is also threatened by deforestation in nearby areas.

“It highlights the imperative role of parks and protected areas where it grows, such as Manu National Park and the Yanachaga–Chemillén National Park,” Farfan-Rios says.

“Hopefully our ongoing study of Incadendron and the intensive long-term forest monitoring will contribute to best practices in reforestation and forest management.”

(Originally published in Wake Forest News)