By Kristen Minogue

Zebra mussels in the Great Lakes, lionfish in the Atlantic and pythons in the Everglades: Large creatures like these generally draw the spotlight when talking about ways to combat invasive species. But for every visible invader, there are hundreds too minuscule to see with the naked eye. These species often slip in unnoticed—and unregulated—in the ballast water of large ships.

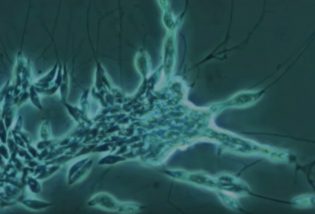

Slime nets are microscopic protists that form colonies like this one, coated in a web-like ectoplasm. Many are parasites that can infect plants, coral, and shellfish.

Some are parasites that can infect humans, plants or other animals. Some can cause toxic algal blooms on the water’s surface. Many are impossible to identify even with a microscope because single-celled microbes can look eerily (and, for biologists, exasperatingly) similar. And sometimes, a single parasite can take on many different forms throughout its life cycle.

At the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center on the Chesapeake Bay in Edgewater, Md., Marine Biologist Katrina Lohan has made it her mission to track the invisible invaders and her secret weapon is DNA. In two recent studies, she and a team of Smithsonian scientists took DNA samples from the ballast water tanks of massive cargo ships. They discovered thousands of microbe types lurking there and DNA enabled the biologists to identify most of these invasive species to genus (the level right before species). Some had never been detected in ballast water before, and some DNA didn’t match anything on the books.

(In a 2016 study, a team from SERC’s Marine Invasions Lab and the National Zoo looked for microscopic protists in ships entering the Chesapeake Bay. One year later, in a study published in the June issue of Diversity and Distributions, the same team looked for protistan parasites entering ports on the East, West and Gulf Coasts of the U.S.)

Marine vessels are one the most prevalent ways invaders cross the globe, as ships must often discharge their microbe-infested ballast water after entering a new port. Below are four groups of invaders that the researchers say bear watching:

Slime net colony found on eelgrass near Washington State, likely “Labyrinthula zosterae,” the parasite behind seagrass wasting disesase. (Dan Martin, University of South Alabama)

The Labyrinthulids (a.k.a. “slime nets”). Coated by a network of web-like ectoplasm, these protists have earned their more common moniker. “They really do look and move like slime nets,” Lohan said. “When you say that term and you look at it, and it’s just like this pulsing genuine net, and you can see the cytoplasm moving within the net—it’s really cool.” While not all slime nets are parasites, they have a stained record. One, Labyrinthula zosterae, is behind seagrass wasting disease, and others have caused diseases in corals and hard clams. Lohan’s team discovered over 150 different kinds of slime nets. One, called Labyrinthuloides haliotidis, kills young abalone shellfish by destroying tissue in their heads and feet.

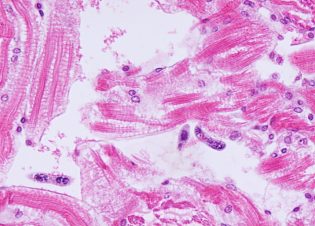

“Hematodinium perezi” in blue crab tissue (Hamish Small & Jeffrey Shields, VIMS)

The Syndinids This order of parasitic dinoflagellates is famous for infecting fish, crustaceans and even other dinoflagellates. The syndinid Hematodinium perezi survives by infecting the tissues of blue crabs. The Smithsonian team found syndinids in ballast water for the first time in the 2016 study. In the 2017 paper, they detected six types of syndinids, two of which were abundant in every sample the team looked at.

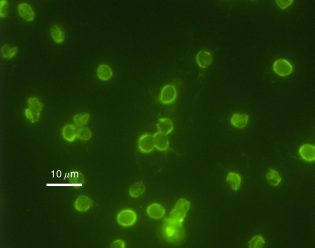

“Cryptosporidium parvum,” an apicomplexan that causes the disease cryptosporidiosis in humans. (HDALindquist/EPA)

The Apicomplexans There are roughly 4,000 known species of Apicomplexans in the world, and they’re all parasites. Their ranks include the infamous Plasmodium, the agent behind malaria. Cryptosporidium struthionis, one of the species the Smithsonian team detected, causes disease in poultry. Lohan and the Smithsonian team also found an unknown species of gregarine, a worm-like protozoan that infects the digestive systems of invertebrates.

Illustration of “Dermocystidium pusula,” c. 1913 (Internet Archive Book Images)

The Ichthyosporeans. This class includes the Dermocystidium parasites, notorious for infecting the gills of fish, and Rhinosporidium, a parasite that can cause lesions to grow on the eyes, nose or other body parts of some mammals and birds, including humans. All ichthyosporeans live with a “host” animal, but they aren’t all parasites. Some are mutualists that benefit their hosts, and some have commensalist relationships, neither helping nor harming their hosts. Like the syndinids, this group had never been detected in ballast water until the 2016 study, and some found in the 2017 study didn’t match any organisms known to science.

The world has woken up to the dangers of invasive species spreading through ballast water. In September 2017 the International Maritime Organization’s Ballast Water Management Convention is slated to go into full force, requiring ships to manage their ballast water for potential invaders. But according to Lohan, microbes aren’t included in the upcoming regulations, and the only parasites included are the cholera-inducing bacteria Vibrio cholerae.

And yet on planet Earth, microbes vastly outnumber visible species, and parasites vastly outnumber free-living ones. Perhaps, as the study suggests, it is time to start giving the invisible organisms their due.

(From Shorelines, a blog of the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center)