By Michelle Donahue

An illustration from Bernhard von Breydenbach’s “Journey to the Holy Land,” 1483-84 (detail)

Tucked away on the lower levels of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and National Museum of American History are some of science’s most glittering literary treasures: rare and unique texts, some written in their authors’ own hand.

The Smithsonian Institution Libraries’ Special Collections contain more than 40,000 books, journals, maps, prints and manuscripts, some handwritten, some painstakingly produced one at a time during the early days of typeset printing. Many date from between the 15th and 19th centuries, but some are older, such as the 13th century illuminated encyclopedia entitled De proprietatibus rerum, written on vellum by the Franciscan professor of theology, Bartholomaeus Anglicus.

The collections, held at the Dibner Library of the History of Science (in the American History Museum) and the Joseph F. Cullman 3rd Library of Natural History (in the Natural History Museum), include first-edition works by notables such as Sir Isaac Newton, Tycho Brahe and Benjamin Franklin, as well as the surviving volumes of James Smithson’s personal collection.

Ferrante Imperato, “Dell’historia natural,” 1599 (detail)

Some of the books are rare simply because not many were made. Before the 1800s, only a small sliver of the population was literate, so the market was tiny. Well-to-do readers usually acquired books through subscriptions, or purchased them from a traveling merchant who visited markets like Venice.

“At most, there were a couple hundred copies of each volume made,” says Leslie Overstreet, curator of rare books at the Cullman Library. “In the early days, it was all very freeform, with nothing like today’s publishing businesses.”

Here are a handful of the more fascinating items in the Smithsonian Libraries’ collection, along with some of its most famous.

Collection of Curiosities

Imperato’s book is not only one of the earliest catalogs of a collection of natural history objects, but one of the first to depict one: Imperato’s own. The precursor to the modern museum, Imperato showed his “cabinet of curiosities” through a detailed woodcut printed in the front of the book, which itself describes specimens in his collection. An herbalist and apothecary in Naples, Imperato privately assembled an impressive range of plant, animal and mineral specimens—possibly as many as 35,000 items. The book is also thought to be the first comprehensive natural history book written in Italian instead of Latin.

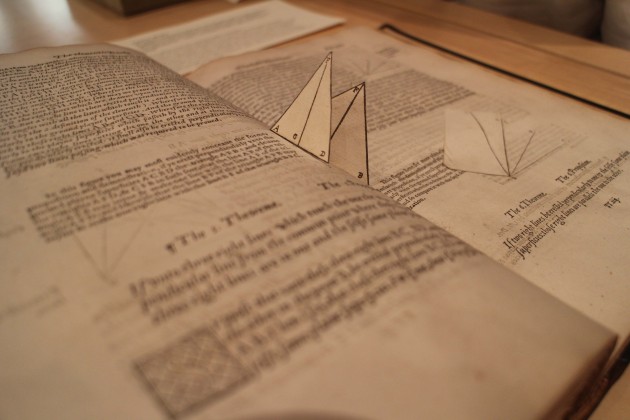

3D Medieval Math

Euclid’s Elements, first typeset in Venice in 1482, was one of the earliest mathematical works to be printed after the invention of the printing press and was for a time second only to the Bible in the number of editions published. For centuries, this work, written in 300 BCE, was required reading for all university students. Sir Henry Billingsley produced the first English translation and preserved useful features from earlier editions, including three-dimensional pop-up diagrams to help students better visualize principles of volume and structure as described by geometric principles.

A New World View

Robert FitzRoy, Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty’s ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, 1839

Nineteenth century surveying ships typically employed a naturalist, whose job it was to collect and document specimens encountered during the voyage. Only 22 years old in 1831 when asked to join Captain Robert FitzRoy’s expedition, Charles Darwin’s observations from that journey were the beginnings of what would eventually upend broadly held opinions in geology and biology. The third volume of FitzRoy’s account is composed of Darwin’s journal and notes from the journey.

Before Audubon

Spending a total of 12 years exploring the forests, fields and fens of today’s American southeast and the Bahamas, Englishman Mark Catesby collected animal, plant and seed specimens to send to botanists and scientists at home. Catesby spent the rest of his life in England producing Natural History, learning to etch plates to produce one of the first folio-sized illustrations for a natural history book. The first fully illustrated book on the plants and animals of any part of North America, it was widely imitated, perhaps most famously by John James Audubon for Birds of America nearly a century later. Catesby’s use of scientific nomenclature for species also inspired Carolus Linnaeus, who adopted 38 of Catesby’s names for birds in his work to revise species naming conventions.

The Ultimate Pilgrim’s Guide to Jerusalem

Intended as a manual for fellow pilgrims, Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio in terram sanctam included phenomena travelers probably never encountered, including unicorns and bearded green men. But the guidebook did include a more useful foldout map of Jerusalem and its surroundings. Drawn in minute detail, the illustration depicts the city as seen from its best vantage point on the Mount of Olives. The painstaking map invites a scavenger hunt with its abundance of surprising minutiae, including a pilgrim’s ship at harbor in Jaffa, and recognizable geographic landmarks.

Writing to the Stars

Galileo wrote this handwritten missive to Peiresc, a French mathematician and natural philosopher, while the astronomer was under house arrest for his support of Nicolaus Copernicus’ heliocentric model of the Solar System. Scholars have identified it as a reply to a letter in which Peiresc described a marvelous water clock driven by a mysterious magnetic force. In reply, Galileo describes a similar magnetic clock he constructed previously, and also thanks Peiresc for his efforts in trying to convince Cardinal Barberini to reduce the restrictions of his confinement. Galileo died while still under house arrest in 1642.