By Michelle Z. Donahue

How do you bring Alexander Graham Bell’s voice to life out of old, cracked deteriorating wax sound recordings? Two words: particle physics.

At the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, inventor Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922) is well represented. His telephone is on exhibition, for starters, as is a photographic portrait of his bearded face. Now, thanks to particle physics, we can even hear his voice.

A high-powered microscope used in experimental physics is to thank for recovering some of the earliest sound recordings made by Bell, including the only confirmed record of old Father Telephone himself speaking aloud. The recording can be heard in a new exhibit, “Hear My Voice,” at the National Museum of American History.

National Museum of American History curator Carlene Stephens examines a glass disc recording containing the audio of a male voice repeating “Mary had a little lamb” twice, made more than 100 years ago in Alexander Graham Bell’s Volta Lab. (Richard Strauss photo)

Museum Curator Carlene Stephens has been caring for many of Bell’s early experiments with recorded sound—gouged into wax, etched on glass plates, scratched on peeling sheets of tinfoil—for nearly 40 years. “The Smithsonian has a very large collection of some of the earliest sound recordings anywhere in the world,” Stephens says.

“We have many examples from Bell’s Volta Laboratory in Washington, D.C., the source of all kinds of sound recording experiments, which is the bulk of our collection.” But these recordings can’t stand up to playing. Many are fragile and cracked, carefully stored and awaiting the day when they can be replayed without damaging them further.

It was the unlikely collaboration between Stephens and physicist Carl Haber that led to Bell’s old records finally getting hauled out of the proverbial attic. Stephens contacted Haber after reading a 2008 New York Times piece that described how sounds had been extracted from a soot-covered piece of paper dating to the 1860s, using methods developed by his group at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Haber’s work at the Large Hadron Collider particle accelerator in Switzerland involved using just such a microscope to examine delicate sensors used to track elusive quarks and subatomic particles found in the universe. He had a notion that a similar method could be used to look at deteriorating old media to create highly detailed 3-D maps of the surfaces of fragile discs and cylinders.

Detail, Alexander Graham Bell phonorecord, wax-on-binder-board disc recording, dated April 15, 1885 with AGB initials. (Richard Strauss photo)

How it works:

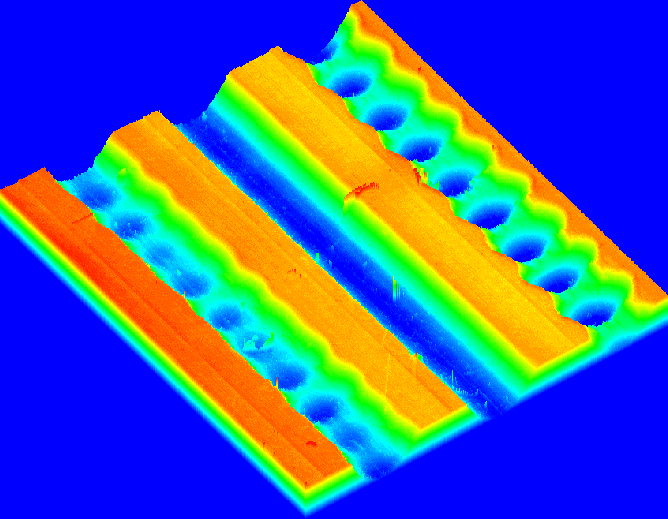

- The computer-controlled microscope peers in ultra-high-definition at the surface of an antique disk or cylinder, and produces a zebra-like pattern of black and white stripes that represent grooves in the media. (“It’s a type of camera, a 3-D camera, that takes pictures not only of the left and right of the seam but also the depth,” Haber says. It creates a topographic picture of the surface of the recording, producing something that looks like a photograph, “but it’s not a photograph, it’s a depth image.”)

- Fine white lines represent the bottom of the groove where sound information is stored.

- The transitions between light and dark lines are assigned numeric values, and in this sense, a digital picture becomes nothing more than a huge table of numbers.

- Using a mathematical process called edge detection, these numeric shifts between light and dark are transformed into curves, mapped as a 3-D model, then read by a digital needle to produce a sound wave.

Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922), Scottish-born inventor and scientist, lived for many years in Washington, D.C. As a young man, he consulted physicist Joseph Henry, the first Smithsonian Secretary, about the feasibility of his telephone invention and was greatly encouraged by Henry. Bell served as a citizen member of the Smithsonian Board of Regents, provided seed money for the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, donated collections to the National Museum, and arranged for the move of James Smithson’s remains from Genoa, Italy, to the Smithsonian Institution in 1904.

One look at the records they came from and it’s a wonder there was any hope at all. Many of the discs are cracked through, or wrinkled, or in pieces; but the voices, sometimes no more than a whisper, are often surprisingly clear.

“What we’ve done so far hints that there is a rich treasure trove here of some of the earliest recordings made,” Stephens says.

“Any time a new source of information is uncovered, that’s when the work begins. We want to know what are they saying, why did they say that? The pursuit is to do more, to have a bigger body of work,” Stephens says.

The scans resulted in the only confirmed recording of Bell’s voice.

This image is a 3-D view of a section of one of disks in the National Museum of American History exhibit “Hear My Voice.” (Image courtesy Carl Haber)

Though other hand-written records indicate he was probably a speaker in several other recordings, it is Bell himself reading off a long list of numbers and then we hear:

“This record has been made by AGB in the presence of Dr. Chichester A. Bell—on the 15th of April, 1885, at the Volta Laboratory, 1221 Connecticut Ave., Wash D.C. In witness whereof—hear my voice. Alexander Graham Bell.”

“I think it is really important that we now have a process of new invention, in the service of invention, to get sound off of these virtually unplayable recordings,” Stephens adds.