By John Barrat

The mite Tuckerella japonica is no stranger to hot water. For centuries untold numbers of this tiny arachnid (cousin to spiders and ticks) have ended up in teapots, invisibly steeping alongside the leaves of the tea plant on which it lives. Today, this Japanese mite is found the world over, having tagged along with the tea plant as a hidden companion.

Despite being sipped and swallowed by humans since the earliest recorded use of tea (between 1066-771 BC), the male and immature stages of T. japonica were identified by entomologists just a little more than a year ago.

Microscopic in size yet mammoth in species diversity, the world’s mite fauna represent one of the last great unknown frontiers of biology, says Ronald Ochoa, adjunct scientist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and an entomologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“No human walks into a doctor’s office with an insect or fungus problem on their body without the doctor saying you have to kill it. But every single person is walking around right now with two or three different species of mites living on their face and they don’t even know they carry them.”

Mites have escaped detection for so long because most are impossible to see with the naked eye. Now new high-powered microscope technology and the Internet are revealing these bizarre creatures and their micro-worlds. The result is a growing surge of scientific interest in mites and a growing database of photographs depicting creatures as wildly strange as any dinosaur.

Many of these photographs are being taken and released by the USDA’s Electron and Confocal Microscopy Unit in Beltsville, Md., a facility that allows scientists from around the world to obtain high-resolution photographs of the mites they are studying.

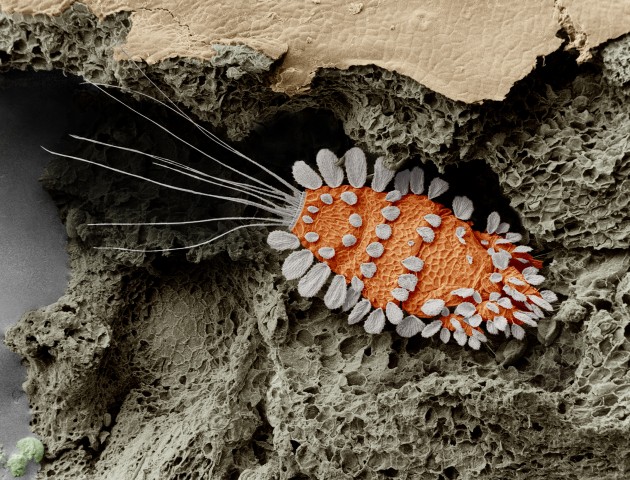

This mite, recently discovered in a coca plantation in Brazil, was named “Excelsotarsonemus tupi” in honor of the Tupi people of Brazil, an indigenous tribe that once inhabited most of Brazil’s coastline. Feather-like setae on its body allow it to ride breezes from tree to tree in the forest canopy. It grows brown fungi on its body for food. (Photo courtesy Chris Pooley / Electron & Confocal Microscopy Unit USDA-ARS)

To get a mite to stand still for a scanning electron microscope portrait, Ochoa and Gary Bauchan, director of the facility, use liquid nitrogen to flash freeze it at a temperature of -321 F. “In milliseconds you freeze not only the tissue of the mites but you are also freezing time,” Ochoa explains. “If the mite is feeding, if it is walking, if it is fighting with another mite, if a predator is killing it, that behavior is frozen for us to see.” Capturing a mite’s behavior is critical because so little is usually known about how they live.

Next, the frozen mite is coated with a fine spatter of platinum metal that allows the scanning electron microscope to record a precise black and white image. The SEM is so powerful that it can focus in on specific parts of a mite’s body—the mouthparts, hair-like setae, legs, and dorsum–in exquisite detail.

USDA acarologist Ronald Ochoa, center, with visiting Brazilian graduate students Jose Rezende, left, and Elizeu Castro (Photo John Barrat)

Feather-like sails

One recent example of the USDA Microscopy Unit’s work is a colorized image of an unnamed white mite collected from a cocoa tree in Brazil by Jose M. Rezende, a visiting graduate student from São Paulo State University. Resembling a green, aerodynamically shaped space vehicle, this mite is equipped with an arrangement of feather-like sails—highly modified hairs called setae—that allow it to glide around the tropical forest canopy on the gentlest breeze.

In addition to sailing, mite setae have many different forms and functions. “Many mites don’t have eyes so they use their setae and setae-like things called solenidia, to feel around their environment, determining if something is good to eat, or something is not good to eat, or if they have met up with a bad guy and need to get away,” facility director Bauchan says.

Most mites are host-specific, meaning that a specific mite species will only feed on one specific plant or animal species. Female mites vastly outnumber males and wander far and wide. Males are homebodies, preferring to remain on their host plant or animal. Finding a male is often difficult; for some mite species it is uncertain if males even exist.

Identifying many new species

Mite researchers also come to Beltsville to use the collection of 1 million mite specimens and an extensive library of mite publications that belong to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. The collection is located there to be close to the USDA’s high-power microscopes and mite experts.

The mite specimens are mounted on approximately 250,000 glass slides and represent previously described mites from all over the world that researchers use for reference in describing new species. The oldest mite in the collection dates to 1911. Glass slides, however, distort the specimens by flattening the mites between two pieces of glass. Scanning electron microscope technology allows viewing mites in 3-D with no distortion.

Grad student Rezende is using the SEM and other microscopes at the USDA to study tiny Brazilian plant mites with big genera names: Daidalotarsonemus, Excelsotarsonemus also known as gliding white mites. Squinting into a powerful stereo microscope, he compares the mouth parts, body parts, legs and setae of mites that he collected on cocoa plants in Brazil with those of the known species in the Smithsonian’s collection. It is a painstaking and time-consuming process that is yielding results.

When he began describing Brazilian white mites in Beltsville about six months ago, “we had two Brazilian Daidalotarsonemus species known,” Rezende explains. “Now we are reaching 40 or 50 species described and this is just the beginning.” In addition to discovering and describing new species and adding them to the Smithsonian’s mite collection, Rezende is also revising earlier species descriptions as he has discovered errors in some of the earlier publications on these mites. Rezende became interested in mites through his advisor Professor Antonio C. Lofego at São Paulo State University. “There is a huge diversity of these mites that are still to be discovered,” Rezende says. “We know so much about the birds of Brazil, about Brazil’s mammals, its reptiles, its insects….but mites? Who knows?”

And this is just the beginning, Ochoa says. For the last 100 years there have been 25 species of these mites described from around the world; now there are 40 new species from just two or three small areas of Brazil. “Twenty years ago Brazil had perhaps, six or seven mite experts,” Ochoa says. “Today, Brazil has more than 350 people working on mites. The same is going on in China, Peru, Egypt and Oman.” Technology and sharing information on the Internet is the driver in this surge of interest, Ochoa explains.

A plant mite of the genus Tenuipalpus from Brazil nicknamed “spinosaurus” because of its crest, shown here at far right. (Photo courtesy Electron & Confocal Microscopy Unit USDA-ARS)

Dinosaurs and mites

On a large computer screen Ochoa pulls up a second SEM image of another newly discovered Brazilian mite by visiting graduate student Elizeu Castro and his advisor, professor Reinaldo J. Feres of São Paulo State University. Castro is studying the mites of the genus Tenuipalpus, also known as flat mites. “This new species was collected from Cerrado biome – a kind of Brazilian Savanna, very dry, that is considered a hot spot for its high biodiversity and that is threatened by the rapid expansion of soybean cultivation,” Castro says.

Castro and Ochoa call this mite ‘spinosaurus’ because it has a crest similar to the dinosaur Spinosaurus. “When I saw this crest the first thing I did was sit down and wonder what animals have these crests? The only animals that happen to have these crests are reptiles and dinosaurs and they used them to regulate their body temperature. Perhaps the mite crest is also for regulating its temperature or humidity,” Ochoa says. “Today, for each dinosaur behavior that someone may show me, I can show you a mite that does that same behavior.”

Remarkably, mites have been crawling around the earth since before the dinosaurs yet many have yet to be discovered.

“If you could grab the Hubble Space Telescope looking into space and instead move it to look to the Amazon and at what is going on between the trees of the rainforest, I am sure you will see a universe of different mites gliding in the air. You and I cannot see them but they are there, floating from one canopy to another canopy, all waiting to be discovered,” Ochoa concludes.