By John Barrat

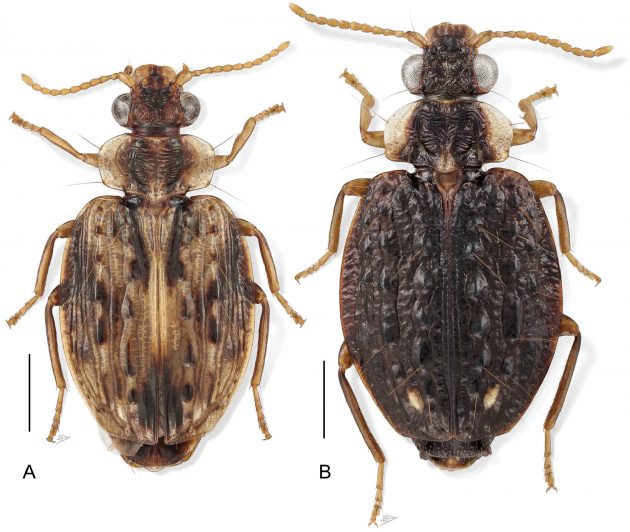

A “Hyboptera angulicollis,” female, found in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Peru, and Suriname; B “Hyboptera biolat,” female, found in Peru. These two beetles were recently named and described by entomologists Terry Erwin and Shasta Henry in a paper in the journal Zookeys. Click photos for larger image. (Digital photo illustration by Karolyn Darrow)

“Somber” is the adjective Smithsonian beetle expert Terry Erwin uses to describe the insects he collects on the forest floor in Peru and Ecuador. “They kind of blend in with the shaded soil and leaf litter,” he points out.

Up high, however, where the bright, hot tropical sun beats down upon the leaves of the forest canopy, some beetle species can be found sporting bright metallic greens and blues.

“You can imagine beetles with these colors sort of blend into the background of green leaves and twigs with the bright sun,” Erwin observes. “It’s a defense against sharp-eyed tropical birds and lizards.”

Entomologists suspect the shiny, reflective metallic coloring also plays a role in insulating these insects from the sun’s burning heat. It is one of many curious features of a number of new canopy beetle species of the genus Hyboptera that Erwin, an entomologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, and Shasta Henry of the University of Tasmania, have just described in a paper in the journal ZooKeys.

Here, Erwin answers a few questions about these newly named beetles.

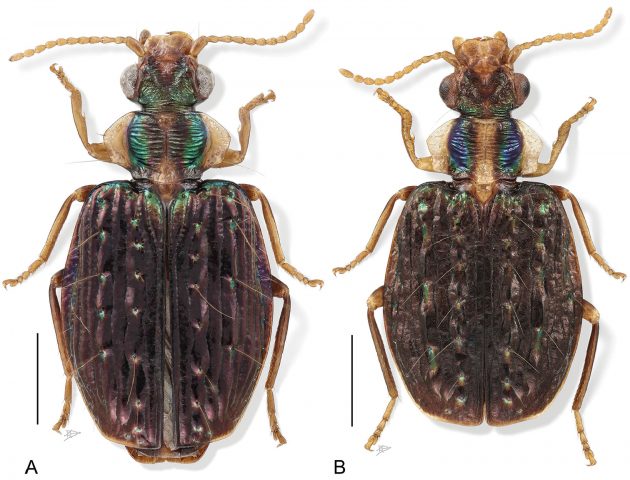

A “Hyboptera shasta,” male, found in Brazil; B “Hyboptera tepui,” male, from Venezuela. These two beetles were recently named and described by entomologists Terry Erwin and Shasta Henry in a paper in the journal ZooKeys. (Digital photo illustration by Karolyn Darrow)

Insider: In addition to metallic colors your paper says these beetles are fast runners. Do they have other defenses?

Erwin: All species in the family Carabidae have defense glands at their “backside” that produce a high variety of noxious chemicals. Some shoot the liquids while others ooze them, either way, they are a great deterrent to predators

For the family I study, the Carabidae, each species has a pair of glands in the back of their abdomen that contain defense chemicals and at the very back two little turrets that spray them. More than 80 different defense chemicals have been identified so far in this particular beetle family.

For example, the famous bombardier beetle that lives on the ground along rivers and other places mix a solution of 25 percent hydrogen peroxide with hydrobenzoquinone. These two chemicals are stored in separate reservoirs in the beetle’s abdomen. When threatened, they squirt them into a mixing chamber right at their butt and the chemical reaction actually explodes.

A “Hyboptera vestiverdis,” female, from Ecuador and Peru; B “Hyboptera scheelea,” female, from Peru. These two beetles were recently named and described by entomologists Terry Erwin and Shasta Henry in a paper in the journal ZooKeys. (Digital photo illustration by Karolyn Darrow)

The reaction creates four lines of defense: the mixture reaches a temperature of 100 degrees Celsius (212 F.), it expels water vapor in the air that looks like a James Bond car letting out a smoke screen, it makes a startling explosive sound, and creates a bitter, noxious chemical taste on the predator’s tongue.

With the bitter taste, a bird or lizard is going to be sticking out its tongue, trying to get the chemical off—giving the beetle a chance to escape. The whole family has these chemicals.

The more primitive Carabidae use formic acid. The higher ones employ all sorts of noxious chemicals.

Insider: The beetles in this paper appear shriveled. Did they dry out and shrink after being collected?

Erwin: No. That is the texture of their elytra, which are the two hard covers protecting their wings. Their elytra are tuberculate, as we say, and that’s very unusual across this family. Small, rounded tubercules stick up from the flat plane of their wing coverings, making them appear wrinkled. The elytra surface of most other Carabidae is smooth with longitudinal lines.

Their elytra are the reason that beetles are the most successful and largest order of any living thing on the planet—it is a hard sheath that provides excellent protection. Beneath their elytra are the beetle’s flight wings. Both elytra and wings are attached to the thorax. When they fly they hold the elytra open and beat the flight wings underneath.

A “Hyboptera dilutior,” male, found in Brazil; Ecuador, French Guiana, Peru, and Venezuela; B “Hyboptera lucida,” female, found in French Guiana. These two beetles were recently named and described by entomologists Terry Erwin and Shasta Henry in a paper in the journal ZooKeys. (Digital photo illustration by Karolyn Darrow)

Insider: How do you collect beetles that live so high up in the jungle tree canopy?

Erwin: I make a giant funnel by stretching rip-stop nylon sheets under and around the trunk of a tree. Then I shoot a fog of biodegradable pesticide up into the canopy. The insects in the tree fall into the sheet, tumble into the center and into a bottle of alcohol. We gather them up after each fogging and then sort through them.

So far, in all of my fogging going way back to 1974, I think we’re getting somewhere close to 15 million specimens collected; insects and their relatives—spiders, centipedes and the like.

If I climbed up with a rope I might be able to catch whatever beetle was within arm’s reach but that’s just no way to collect. Fogging really samples the entire canopy population—you get everything, so you know what insects are associated.

A “Hyboptera tiputini,” male, from Ecuador, Colombia and Peru; B “Hyboptera viridivittis,” male, found in Brazil. These two beetles were recently named and described by entomologists Terry Erwin and Shasta Henry in a paper in the journal ZooKeys. (Digital photo illustration by Karolyn Darrow)

For example, some of the beetles in the family I study, the Carabidae, are predators that lurk under the webbing of psocids or booklice. Booklice adults spin nets that look like spider webs. Their young live under these nets for protection and my beetles have evolved to sneak under the net and have a meal.

So when I get certain beetle species down after fogging, if some booklice species appear as well, I know I may have a predator-prey relationship right there in the collection.

Insider: The species in this paper appear remarkably similar. What physical characteristic is most reliable for telling them apart?

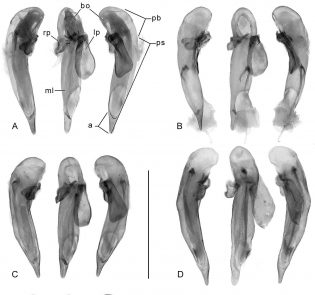

The uninflated male reproductive organs of: A “Hyboptera angulicollis”; B “Hyboptera biolat”; C “Hyboptera vestiverdis”; and D “Hyboptera tiputini” (Digital photo illustrations by Karolyn Darrow)

Erwin: The genitalia, both male and female, are really the best characters to tell them apart and you have to study them under a microscope.

It is important to note that on an evolutionary timescale, the selection of characters of the genitals within a genus occurs on a different scale than visual characters, such as coloration, which is regulated by predators. The evolution of genitals is tied to reproduction.

What we’ve discovered so far is that within a genus the female genitalia appears pretty much alike. The male genitalia consists of a penis with a sac inside that inflates inside the female and it has spines and various shapes that exactly fit the female’s vagina.

The old literature calls this fit “lock and key” mating, the theory being that this is why a species stays a species because a male of a different species has the wrong key for a female’s lock. Today, it has become a controversial issue that is still being sorted out.

From what I see in the Carabidae, the male has to fit into the female. We hardly ever, ever see any kind of hybridization between species of these beetles.

Insider: As an expert in Carabidae is there any area of their body, other than genitalia, you can quickly look at and tell species apart?

A “Hyboptera tuberculata,” female, from French Guiana, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Perú, and Suriname; B “Hyboptera verrucosa,” female, from Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador, French Guiana, Panama, Peru, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, and Venezuela. These two beetles were recently named and described by entomologists Terry Erwin and Shasta Henry in a paper in the journal ZooKeys. (Digital photo illustration by Karolyn Darrow)

Erwin: After working on these things for more than 50 years, I tell my students that these beetles, just like a giraffe or a rhinoceros, they have a personality. In sorting through specimens on a large scale anybody can discern a giraffe from a rhinoceros.

But then you come down into this next fractal universe that is much smaller than ours, you have to be able to see into that fractal universe and look at the same kind of characters that anybody would see on a rhinoceros. Beetles have characters just like any other species, it’s just that you have to have experience and focus in on them.

The prothorax, which is the part of the beetle behind the head and in front of the wing covers, is a really good personality indicator. There are little subtle things.

For example, look at the pictures in this recent paper, forget about the rest of the beetle, just look at the prothorax and you can see that they are subtly different.

Insider: How many more species of beetles remain to be discovered?

Erwin: Gazillions. I study the whole family of Carabidae in the New World for which there are some 3 or 4 hundred genera and about 10,000 described species. Every time we publish a paper like this new one it triples the number of species that are known in a genera and this is really from very few collection sites.

A “Hyboptera apollonia,” male, from Panama and throughout southern Central America north to Costa Rica; B “Hyboptera auxilidora,” male, found in Texas and Panama, and in between those extremes only in Mexico, Honduras, and Costa Rica. These two beetles were recently named and described by entomologists Terry Erwin and Shasta Henry in a paper in the journal Zookeys. (Digital photo illustration by Karolyn Darrow)

If we had a battalion of young coleopterists and we could put up a fogging station every 500 kilometers in a big grid across the Amazon we would be getting lots and lots, and lots of new species—especially from the canopy.

This paper describes new species for which very little is known about their behavior and life history. That is for the next generation to find out.