by John Barrat

Photograph of the Stevens Family outside their home in Linn Creek, Missouri, ca. 1905 by an unidentified photographer. Silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper

(Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Jackie Bryant Smith)

Clutching a revolver against his chest, an unidentified African American Union soldier stares out from an 1861-1865 Civil War tintype. Barack and Michelle Obama relax together on a sofa in their Chicago home in a 1996 black and white portrait taken by Mariana Cook. An African American mother smiles joyfully at her newborn baby in a 1952 photograph by Robert Gailbraith from the series “Reclaiming Midwives: Stills from All My Babies.” Breathtaking, tragic, solemn, overwhelming, exuberant are but a few of the adjectives that try but fail to capture the radiance and breadth of the some 30,000 photographs now in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Started by curators Michèle Gates Moresi and Jacquelyn Serwer, this remarkable collection has lately been growing with the added expertise of Aaron Bryant, one of NMAAHC’s curators, and Rhea Combs, head of the museum’s Stafford Center for African American Media Arts. “Michelle, Jackie, Rhea and I work as a team, acquiring photographs for the museum,” Bryant explains. Other curators, however, also collect images relevant to their particular interests.

Here Smithsonian Insider asks Bryant a few questions about what type of photos he looks for and how he acquires them for the African American History and Culture Museum.

Portrait of a couple on a motorcycle outside of Anderson Photo Service studio ca. 1960, by Rev. Henry Clay Anderson. Silver and photographic gelatin on acetate film (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

Q: Where do you find images for the collection?

Bryant: One way is to build relationships directly with photographers. Our job is to share history and preserve American legacies, and sharing and preserving the work of photographers who have documented our nation’s culture and history is part of that.

Equally important, however, are the scores of donors who have reached out to the museum. You’d be surprised and touched by the number of people who have donated their collections, including family albums with images that extend as far back as the 19th century.

The provenance and personal stories behind certain images, as well as the donors’ reasons for wanting to donate, are incredibly moving. People supporting NMAAHC’s vision by helping to build the museum through donating family treasures has real value to us. Our collection is like a national family album of sorts, with thousands of different branches in the family tree, and each one is significant to telling a broader story. Our donors become an important part of a national history, and the sense that the museum is working with a community of people as part of a national family aligns with our mission.

We’ve also gotten certain photographs from collectors, auction houses, and galleries. They’ve been instrumental in helping us identify specific, hard to find images that are essential to stories we want to tell.

Autographed photograph of LeRoi Jones, Jan. 31, 1962 by Carl Van Vechten. Silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

Q: Do you only collect originals?

Bryant: Yes. A photograph is actually an object in many ways. Just as museums are most interested in collecting original three-dimensional artifacts, we collect original photographs, negatives, digital negatives, or digital scans from negatives, depending on why and how the photo will be shared with the public. Antique and vintage photos and negatives, are different from the contemporary images that sometimes come to us as digital negatives from the photographer.

In addition to being an object, though, images are also archival documents. So we’d want to collect images as original archival material as well. Our collection of Robert Houston’s images from his time at Resurrection City during the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign is an example. In addition to the journal he kept at the time, we also have images he shot as a visual diary of his experiences with the poverty campaign. The collection includes vintage prints and slides. He made an earlier donation of high-resolution digital scans of negatives. As a museum operating in the 21st century, we recognize that the original might also include digital files from digital cameras or high-resolution scans of negatives, which helps to stabilize images.

Views of Thomasville and Vicinity: 44 Weighing Cotton ca. 1895 by photographer A. W. Möller. Unidentified women and men. Albumen and silver on paper mounted on cardboard. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Norman and Sandra Lindley)

Q: Are you looking for images from specific periods in American history?

Bryant: We’re building a collection that reflects America’s history, African American culture, and a history of photography. So in addition to covering people, places, events, subjects, and time periods, the collection is also an evolutionary survey of photographic processes and mediums that cover a spectrum of time periods. The collection ranges from 19th century daguerreotypes to digital images as recent as several months ago. In fact, we have cell phone images from Devin Allen as examples of a new photographic medium in art, social media, and photojournalism. Allen captured images of protests in Baltimore, which Time magazine and a number of other media outlets later published after they went viral online. Aperture recently published a few in its special issue “Vision & Justice,” which is getting lots of global attention in the field.

“Positive Reflections,” unidentified man, Oct. 16, 1995, by photographer Roderick Terry. Silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Roderick Terry)

Our collection also houses traditional mediums like gelatin silver prints, magic lantern slides, carte-de-visites, cabinet cards, ambrotypes, tintypes, negatives and transparencies, and a host of other examples of how photography has evolved from its early history in the 1800s to today.

We’re also considering the evolution of artistic genres, from Pictorialism and the painterly kinds of images of late 19th–century early modernism to contemporary art photography, straight photography, portraiture, and abstraction. We extend beyond the historicity of social documentary and photojournalism a bit to include traditional genres and interesting hybrids, where images are created through innovative and unexpected mediums. Since the museum also collects visual art, artistic genres in photography is something we will consider more as we move forward.

In this tintype an unidentified African American Union soldier with a moustache and beard, holds a pistol across his chest. His buttons and belt buckle are hand-colored in gold paint. The hand-coloring on the buckle reads “Z O”. Thermoplastic case with brass hinges and red velvet liner. (Collection of the National Museum of African American History and Culture)

My particular interests are in sociopolitical history, cultures of everyday life, and art photography. There are lots of photographers who create social documentary photography that’s also considered art. Sometimes the purely social documentary images give us a lot of cultural and historical information.

Q: Please give an example?

Bryant: We’ve published four books focusing on the museum’s photography collection and will soon publish a fifth. The first book was Through the African American Lens. In our second book, Civil Rights and the Promise of Equality, there is a photo by James H. Wallace taken in 1964 of students in Chapel Hill, N.C. participating in a July 4, protest against segregation. In looking at the image, we’d consider ways the photograph might document an American story from different perspectives, including African Americans. It’s 1964. What was Chapel Hill like at that time? What was North Carolina as a cultural and ideological space like for people at that time? And what was the university like for students, as well as for the people working or living in the area?

Photograph of Senator Henry Hall Falkener and family ca. 1905. Unidentified photographer. Silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Margaret Falkener DeLorme, Waldo C. Falkener, Cameron S. Falkener and Gilbert E. DeLorme)

In North Carolina by 1963, Bob Jones was leading the emergence of one of the largest Klan groups in the country. The Klan had become notorious in North Carolina and the effects of their presence were felt generations later. So the Chapel Hill images have a certain context that goes beyond the two-dimensionality of the photograph.

No matter the period, it’s the history surrounding the image that helps us tell American stories. African American perspectives can be the prism for interpreting the experience. Then there might be a broader contextualization in which the photo and the moment it captures is placed within a larger history. What led to that particular protest in Chapel Hill, for example, and how might the moment reflect 1964 America?

Q: How is your work different than someone from another history museum?

Bryant: The museum and its collection were built from scratch. We started without a collection or facility, but now we have a museum on the National Mall with roughly 30,000 images. We’ve collected to build a foundation for the photography collection, while hoping to add to the canons in various fields in a way that shifts cultural paradigms and historical narratives.

We also were aware that we were building a 21st century collection for a museum that would serve several generations. So while collecting to preserve a distant past, we also collect to reflect contemporary histories and issues as well. We built the collection with the idea that we are about the present and the future, as well as the past.

Untitled (photograph from the Film & Photo League Archive) by unidentified photographer, 1931 – 1936. Silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

Q: What is one of your favorite recent acquisitions?

Bryant: We recently accessioned photographs of Black Lives Matter protests in different cities, including Ferguson and Baltimore. This would be a case in which we accessioned images with history, the present, and the future in mind.

The photographs were taken by Zun Lee, Sheila Pree Bright, Jermaine Gibbs, and Devin Allen. Allen is the millennial sensation, whose images of unrest in Baltimore went viral on social media. Allen democratized photography in a way that impacted the field for future generations, using social media, rather than mainstream media, as a voice and platform. Jermaine Gibbs is a commercial photographer in Baltimore, who also captured images of the city’s unrest. Zun Lee and Shelia Pree Bright have also gotten media attention in recent years as part of a new generation of socially conscious photographers. They are redefining traditions. Sheila is known for her series 1960NOW! and Plastic Bodies, while Zun has received recognition for his series of found Polaroids, Fade Resistance, as well as his Father Figure series. Acquisitions that involve contemporary social histories, while working with living photographers like these, are exciting.

However, another one of my favorite acquisitions was also one of my first acquisitions for the museum. Our chief curator, Jackie Serwer, and I met with a donor, Simone Durrah Logan, who wanted to donate her family photos from the 19th and early 20th century. They were a wedding gift from her dad. Most of the images were taken in Yankton, S.D.

Few people think about the history of African Americans in places like North and South Dakota during Reconstruction. When we think of African American history, we often think of the east coast, but African Americans were building communities and creating cultures all over the country. Simone’s family images help us to create new narratives and perspectives and share stories about what attracted communities of African Americans out west following Emancipation.

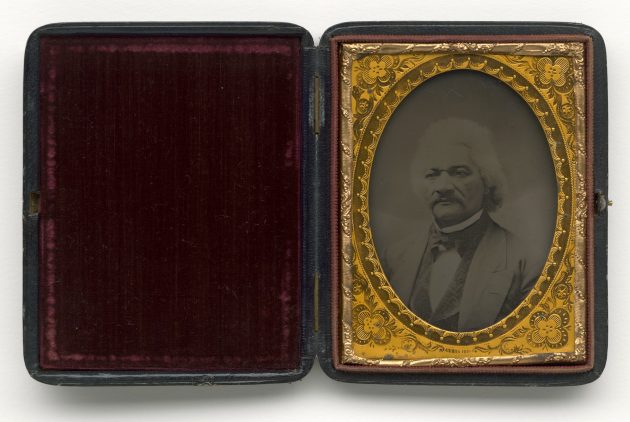

Ambrotype of Frederick Douglass, 1855-1865, by an unidentified photographer. Collodion and silver on glass photographic plates, leather. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

Q: How is a strong photo collection important to a museum?

Bryant: Images have power. As a form of language, visual data influences the way we create social meaning and share cultural knowledge. Seeing and then interpreting what we see is critical to our understanding the world from a particular lens or worldview.

Additionally, images have an ability to communicate beyond the power or necessity of words. It is true that a picture can be worth a thousand words, particularly in contemporary cultures that are visually driven. Images offer “thick descriptions” of people, events, places, and particular moments in time. It’s why social media is so popular and instrumental in present-day cultures.

Images also offer first-person perspectives on historical events that help us see and understand from different points of view. Photographs allow us to immerse ourselves in the histories and moments caught in a camera’s lens.

Photographs can be objects or works of art. They can be a form of archival texts that document time, or windows into different cultures and worlds from our past. I like to think that photographs can bear witness. They provide visual evidence of a culture as a testament to our nation’s history.