By Michelle Z. Donahue

Close up of “A Cruise Through Bikini Bottom” by Dallin Maybee (Northern Arapaho/Seneca). (Photo by Joshua Stevens, NMAI)

Wild-eyed and astride a red seahorse, SpongeBob SquarePants gallops through Bikini Bottom brandishing a spatula while decked out in an American Indian headdress, moccasins and leggings. Drawn by Native American artist Dallin Maybee (Northern Arapaho/Seneca) the cartoon character is a chunk of modern culture on the warpath inside an ancient storytelling tradition that dates back to petroglyphs. The artwork, A Cruise Through Bikini Bottom, hangs in a new exhibit at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City, “Unbound: Narrative Art of the Plains.”

Great Plains Indians have long used pictorial storytelling, or narrative art, to portray historic or noteworthy accomplishments by its members. At Deer Medicine Rocks in Montana, for example, their ancestors carved petroglyphs of tipis, wild game and battle scenes. In the last several centuries, warriors’ deeds were committed to history on buffalo hide and other animal skins. More recently, during the reservation era and beyond, Native Americans began incorporating muslin and then paper, making use of materials at hand to preserve memorable scenes and actions from their cultures.

“Mountain Chief, depicting Blackfeet leader Mountain Chief,” 2012. Terrance Guardipee (Blackfeet). (Photo by Ernest Amoroso, NMAI)

The exhibition “Unbound” explores the evolution of this richly illustrative form of storytelling. Based upon 17 historic and 9 contemporary pieces from the museum’s collection, “Unbound” also includes 50 new pieces commissioned just for the exhibit.

Curator Emil Her Many Horses, who is active in the Native American art scene both as an artist and as an observer, said the show demonstrates the long continuum of Plains narrative art and how is has been carried forward into the present.

From images of the war deeds of White Swan, a 19th century scout for General Custer, to Lauren Good Day Giago’s celebration of her grandfather Blue Bird’s experiences in the Vietnam War, narrative art often depicts battle scenes.

“Red Bear’s Winter Count,” 2005, Martin E. Red Bear (Hehaka Gleska (Spotted Elk), Sicangu Lakota (Rosebud Sioux)/Oglala Lakota (Oglala Sioux), b. 1947) Acrylic paint, canvas. (Photo by R.A. Whiteside, NMAI)

“One might paint their buffalo robe, their personal robe, with war deeds,” Her Many Horses, explains. “I compare that to a modern military uniform with ribbons, so this was their record of who they were and their accomplishments in battle.”

The earliest piece included in the show dates to around 1840, but as the art progresses into more recent decades, the scenes move beyond depictions of war.

In several instances, the material on which the scene is drawn informs the scene itself, such as Chris Pappan’s 2012 Break From Tradition, 21st Century Ledger Drawing No. 58. Drawn on paper that had been used to record a real estate transaction, Pappan depicts a delegation of 19th-century Osage tribal members who visited Washington, D.C. to discuss land and treaty rights with the government.

“He’s talking about land deals and respecting the treaty,” Her Many Horses said.

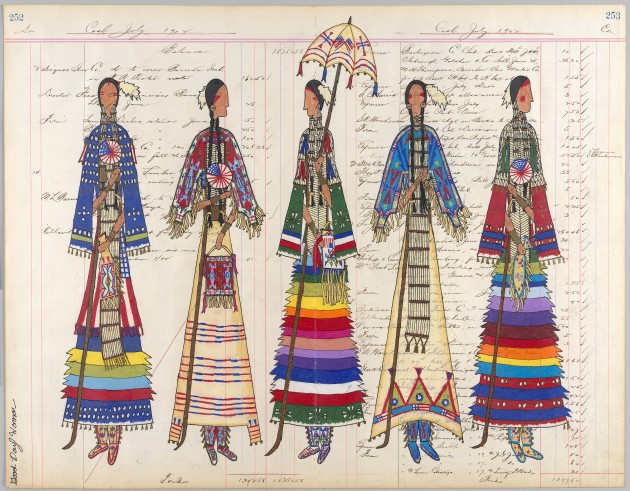

“Independence Day Celebration,” 2012. Lauren Good Day Giago (Arikara/Hidatsa/Blackfeet/Plains Cree, b. 1987). Antique ledger paper, colored pencil, graphite, ink, felt-tipped marker (Photo by Ernest Amoroso, NMAI)

Despite being a contemporary artist, Pappan references an issue central to the 19th– century Native American experience. Other contemporary artists in the show tackle questions of what the modern era means for traditional cultural identity.

Dallin Maybee, a Northern Arapaho and Seneca artist, explores Native American identity, as well as the ongoing exchange between traditional and modern Indian life that has allowed these cultures to persevere, evolve and thrive.

In one of his works, Indian Prosecutor, Maybee depicts himself in a suit and tie topped off with a traditional headdress, depicting a time in his life when he worked as a prosecutor for the Gila River Indian Community near Phoenix, Arizona. In A Cruise Through Bikini Bottom, Maybee shows one of his children’s favorite cartoon characters, Spongebob, reimagined with Native American regalia.

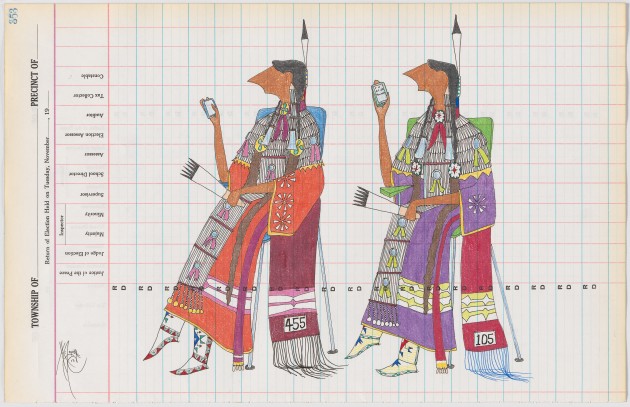

“4G Better than One-G,” 2012. Dwayne Wilcox (Oglala Lakota, b. 1954). Antique ledger paper, graphite, colored pencil, ink. (Photo by Ernest Amoroso, NMAI)

Lauren Good Day Giago, whose grandfather Blue Bird served in Vietnam as a young man, is one of a growing number of female artists who are appropriating this art form. Her creation of A Warrior’s Story: Honoring Grandpa Blue Bird, a painted dress that depicts a powerful moment from her family’s history, revives a traditional art form that honors the deeds of a male relative. Customarily, a woman would have sewn the dress. Only male tribal members would have painted it.

Her dress shows her grandfather in green fatigues, surrounded by images of modern and traditional American warfare: rifles, bows and arrows, a hatchet, flags. Blue Bird wears a sacred eagle plume given to him by Chief Drags Wolf, a leader of the family’s Hidatsa tribe, which would protect him as long as he carried it. During a heavy firefight, Blue Bird lost the plume along with his helmet, and was restrained by his fellow troops from retrieving it. At home in South Dakota, Blue Bird’s father dreamed of Drags Wolf, who delivered the plume and told him that as the feather is returned to the tribe, so Blue Bird will also be returned safely.

“A Warrior’s Story, Honoring Grandpa Blue Bird,” 2012. Lauren Good Day Giago (Arikara/Hidatsa/Blackfeet/Plains Cree). Muslin, wool cloth, dye/dyes, brass, cotton thread, brass beads, satin ribbon, imitation sinew. Purchase made possible by Devon Hutchins. (Photo by R.A. Whiteside, NMAI)

“The plume came back in the dream, and my grandfather did too,” Giago said. “The dress depicted everything he was: his warrior story, the right to make war bonnets and his different personal stories of being a rancher. I put all of that on the dress.”

Some of Giago’s other contributions to the show depict women in brightly colored dresses—a subject that was rarely, if ever, shown in traditional narrative art.

“Conductors of Our Own Destiny,” 2013. Dallin Maybee (Northern Arapaho/ Seneca). Buffalo hide, acrylic paint, beads. (Photo by Ernest Amoroso, NMAI)

“I left it up to them to come up with what they wanted to depict,” Her Many Horses said of the artists who were invited to contribute to the exhibition. “For a while, this tradition died out, but these artists have revived it. They’ve brought out the contemporary issues of today while still showing the continuum of the culture.”

The breadth of the narrative art on display at the Heye Center “shows who we are as a people,” Giago adds. “We’re these native people, but live in a living, thriving, breathing culture.”