By Maria Anderson

The Arrow Motel sign in Espanola, N.M. The Arrow Motel has been shuttered for years, yet the sign remains, a landmark in a small town. Indian names and imagery are familiar, authentic, and American. From “Americans,” an exhibition at the American Indian Museum. (Photo by Jim Good)

A baseball mascot, a tub of butter and a missile. These three seemingly unrelated items share something in common which has been a part of American mainstream culture for centuries.

Each carries an American Indian image or name. The Cleveland Indians’ mascot, the Land O’Lakes butter maiden and the Tomahawk flight test missile are among hundreds of examples of American Indian-themed objects featured in “Americans,” a new exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

The exhibition explores how American Indian images, names and stories have always been a ubiquitous part of our nation’s history and contemporary life.

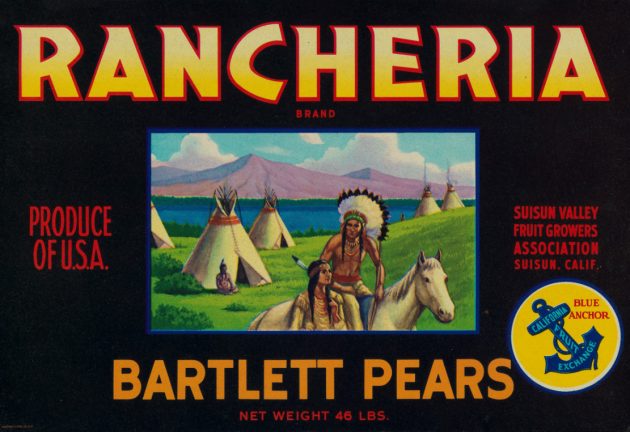

Rancheria Brand Bartlett Pears crate label, 1940s. This crate label depicts an Indian village scene designed to entice consumers to purchase Rancheria Brand pears. Created by the Schmidt Lithograph Co. in San Francisco, the label appeals but is also misleading. California Indians have never worn eagle-feather headdresses or lived in tipis. Gift of Lawrence Baca, 2015

From the stories we all think we know—the first Thanksgiving, for example—to contentious issues such as renaming a football team, the exhibition seeks to answer one question: How is it that American Indians can be so present and so absent in American life?

“We wanted to create an exhibition that explores the paradox that is American Indian imagery,” explains Paul Chatt Smith (Comanche), associate curator at the museum. Smith is co-curator of “Americans,” along with curator Cécile R. Ganteaume.

“It is no great revelation that American Indian names and images are found everywhere,” Smith says. “What we wanted to show is how this phenomenon is far more massive, broad, weird and singular than most people realize.”

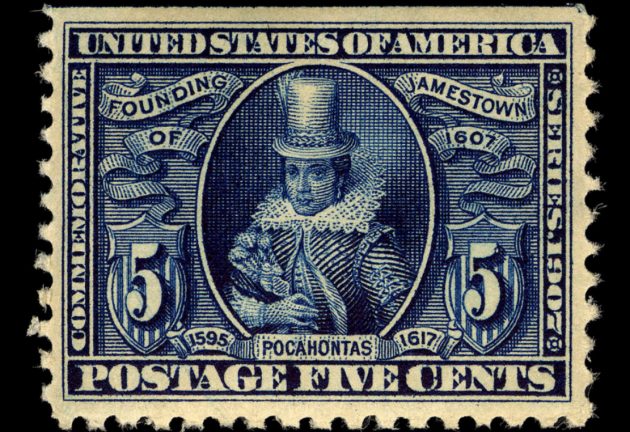

Pocahontas Commemorative postage stamp, United States, 1907. This stamp was one of three issued in 1907 to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown, Va. (Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum)

For centuries, people have been surrounded by American Indian names and symbols across every product imaginable.

“There’s nothing else like it in any other country in the world,” Smith says. “No other minority has captivated and come to identify with the country itself quite like Indians in the U.S.”

In planning “Americans,” Smith and Ganteaume delved into what a typical museum visitor might expect walking in.

“Whether they have 20 minutes or two hours, ‘Americans’ gives visitors a chance to learn about the history, not just of American Indians, but of the nation,” Smith says.

A banner with the insignia of the U.S. Army’s Second Infantry Division adorns a hangar housing an Apache helicopter at Camp Humphreys, South Korea. (Photo by Gregory T. Vaughn)

“The exhibition needed to be relevant and effective for our visitor,” Ganteaume says. “We needed to get across that the history of American Indians is the history of the country. It’s their own history. We went to great lengths to make it clear we are talking about their history.”

“Americans” tackles this by presenting stories that have been a fixture in our national narrative for centuries, but whose details or significance are not well-known.

The story of the first Thanksgiving is told in a video that explains how a “brunch in the forest between Indians and newly arrived people from England” was saved from being a footnote in our history and became one of the country’s most widely celebrated holidays.

This video is in the “Americans” exhibition at the American Indian Museum.

Another gallery tells the story of Pocahontas, the young Powhatan woman whose marriage to tobacco planter John Rolfe (not John Smith) in 1614 was so momentous that it brought about a break in warfare between the American Indians and Europeans known as the “Pocahontas Peace.”

The exhibition also dedicates a gallery to the Battle of Little Bighorn, posing the question: “Who really won the Battle of Little Bighorn?” The answer: “It’s complicated.”

In 1876, the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne wiped out U.S. Gen. George A. Custer and 200 of his men in Montana. The nation was in shock.

Greetings from Cherokee, Iowa postcard, ca. 1949. From the exhibition “Americans” at the American Indian Museum. Courtesy The Newberry Library, Chicago, IL.

Despite the fact that eight months later the U.S. won the Great Sioux War and confined nearly all Plains Indians to reservations, Custer’s defeat was burned into the nation’s memory forever. For years, the story has been told in books, plays, reenactments, movies and more.

“Americans” also explores the story of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, better known as the Trail of Tears. President Andrew Jackson signed this law, which envisioned the U. S. without American Indians. It led to the country’s westward expansion at the expense of American Indians.

“We understand that for many people some of this history and imagery is difficult to process,” Smith says. “Our goal is not to make people feel defensive or that we’re lecturing them. That is why we put a lot of thought into creating an exhibition environment that is inviting and comfortable.”

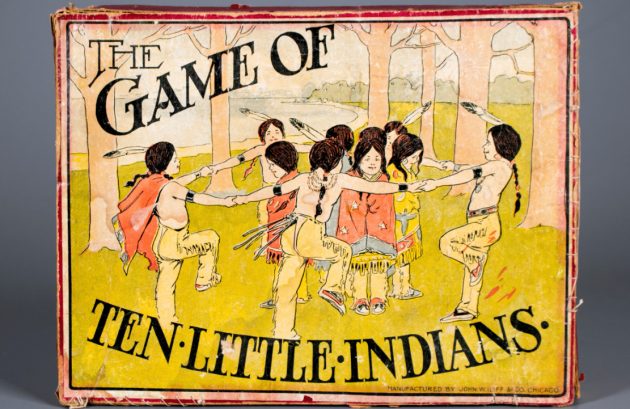

“The Game of Ten Little Indians” box, ca. 1900. Like many children’s rhymes, “Ten Little Indians” cheerfully tells a gruesome tale. You start with ten, and end up with none. From the exhibition “Americans” at the American Indian Museum. Courtesy of The Strong Museum, Rochester, N.Y.

“Americans” was built from the ground up with visitors in mind.

“We even included couches, so people can take a moment to sit and think about what the information they are reading means to them,” Smith adds.

As the national museum devoted to American Indian history and issues, Ganteaume says the team takes that responsibility seriously.

“We want our visitors to recognize that the history Americans and American Indians share has had a lasting impact on the country. It has shaped American national consciousness and who Americans are as a people,” she says.