By Marilyn Scallan

“Convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell.”—Frances Glessner Lee

A woman’s body lies near a refrigerator. Around her are typical kitchen items—a bowl and rolling pin on the table, a cake pulled out from the oven, an iron on the ironing board. What happened to her? Was it an accident? Suicide? Natural causes? Murder?

Frances Glessner Lee, “Kitchen” (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. (Image courtesy Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore)

This scene is not from real life but inspired by it. It is from one of 19 miniature dioramas made by Frances Glessner Lee (1878–1962), the first female police captain in the U.S. who is known as the “mother of forensic science.”

The dioramas are featured in the exhibition “Murder Is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death,” on view Oct. 20 through Jan. 28, 2018, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery.

Lee designed them so investigators could “find the truth in a nutshell.” This is the first time the complete Nutshell collection (referred to as simply the “Nutshells”) will be on display: 18 are on loan from Harvard Medical School through the Maryland Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, and they are reunited with the “lost” Nutshell on loan from the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests, courtesy of the Bethlehem Heritage Society.

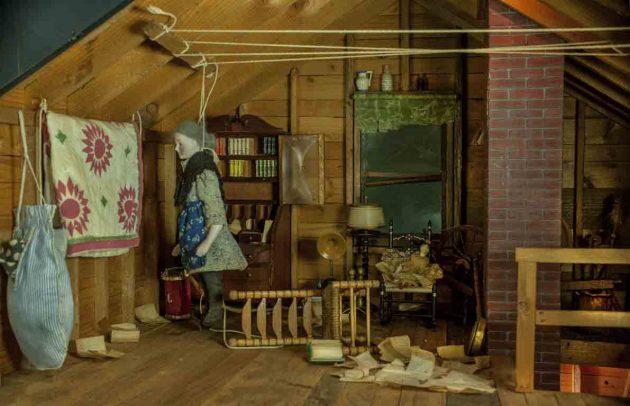

Frances Glessner Lee, “Attic,” about 1943-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. (Image courtesy Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore)

The Nutshells bring together craft and science thanks to Lee’s background as a talented artist and criminologist. Born in Chicago, she was the heiress to the International Harvester manufacturing fortune. She had an avid interest in mysteries and medical texts and was inspired by Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s fictional detective who relied on his powers of observation and logic.

Lee married at 19, had three children and after her marriage dissolved, she began to pursue her these passions. She met George Burgess Magrath in 1898. Magrath studied medicine at Harvard and later became a medical examiner—he would discuss with Lee his concerns about investigators’ poor training, and how they would overlook or contaminate evidence at crime scenes.

After receiving her inheritance, Lee began working in a New Hampshire police department and became a police captain. In 1943, she began designing her Nutshells.

Frances Glessner Lee at work on the Nutshells in the early 1940s. (Image courtesy Glessner House Museum, Chicago)

Lee’s Nutshells are dollhouse-sized dioramas drawn from real-life crime scenes—but because she did not want to give away all the details from the actual case records, she often embellished the dioramas, taking cues from her surroundings. They are not literal, but are composites of real cases intended to train police to hone their powers of observation and deduction.

They are intricately detailed and highly accurate, with each element potentially holding a clue. Lee hired Ralph Moser, a carpenter, to help build the dioramas. Moser would build the rooms and most of the furniture and doors. Lee was extremely exacting, and the elements of the Nutshells had to be realistic replicas of the originals.

Lee crafted other items, including murder weapons and the bodies, taking great pains to display and present evidence as true to life as she could. She would hand-knit tiny stockings with straight pins and address tiny letters with a single-hair brush. Real tobacco was used in miniature cigarettes, blood spatters were carefully painted and the discoloration of the corpses was painstakingly depicted.

The details mattered: they could give hints to motive; they could be evidence. A Nutshell took about three months to complete, and cost Lee $3,000 to $6,000—or $40,000 to $80,000 today.

Frances Glessner Lee, “Striped Bedroom” (detail), about 1943-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. (Image courtesy Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore)

Lee’s Nutshells are still learning tools for today’s investigators-in-training, so the solutions are not given in the exhibition. Visitors to the Renwick Gallery can match wits with detectives and channel their inner Sherlock Holmes—especially when the case is a particularly tough nut to crack.