By Evan Berkowitz

Evacuees were allowed to bring only what they could carry. The Watanabe family brought this wicker suitcase with them to the Minidoka camp in Idaho.

When Barbara Watanabe, a museum specialist in the Anthropology Department of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, first saw her grandmother’s suitcase as a child, she didn’t know the tragic history imbued within its woven walls.

Today, the reddish valise greets visitors to “Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II,” which opened in February in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History Albert H. Small Documents Gallery.

It has weathered corner guards at its edges and “WATANABE 17703” written across its top in the sort of white ink people once used to caption photographs. Its luggage tag sits beside, same name and same five-digit number written out on its aging paper.

“It wasn’t until 10 years ago,” Watanabe says, “when I went to the basement of the house, helping to clean things out after my dad died [that] I realized, ‘Look at the number and the tag on it: That’s the camp. … This was grandma’s suitcase that she took to the camp.’”

James Watanabe was issued this work release identification card. Watanabe was among those allowed to leave the camps temporarily for seasonal jobs.

Watanabe’s father and paternal grandmother were incarcerated at Minidoka, a Japanese incarceration camp in Idaho, during World War II. They were among roughly 120,000 people of Japanese descent forced from their homes under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066.

That order, on view in “Righting a Wrong,” gave the U.S. War Department sweeping powers to incarcerate people under the auspices of national security, although the exhibition clearly details the anti-Asian attitudes prevalent at the time.

The exhibit explores complex questions of what terminology to use in discussing Japanese American Incarceration and takes a hard look at the prejudices that helped make Executive Order 9066 fathomable 75 years ago.

Most of all, though, this story is told through objects: clothes and family photos; family documents, artworks and an in-camp high school yearbook called “Ramblings” with neatly drawn barracks on the cover.

Seishi Oka, who was incarcerated at Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona, speaking at a February press preview at the National Museum of American History.

“Even though the executive order document is sort of the key to the show, we wanted to humanize it,” Jennifer Jones, armed forces curator at NMAH says. “Having an image of a family with all of their family tags is just a really powerful and striking image.”

“To have the artifacts themselves in a juxtaposition to that is one of the things we wanted to show,” Jones continues, “the human side of the story.”

Watanabe concurs.

Visitors benefit by “actually seeing an object, something that was there,” she says. “All you have to do is look at the suitcase and you can see.”

The object reveals insights that a written account or photograph simply couldn’t, like how Watanabe’s grandmother, who never learned to write English, struggled to write her last name in that white ink.

The Masuda family, owners of the Wanto Grocery in Oakland, California, proclaimed that they were American, even as they were forced to sell their business before they were incarcerated in August 1942. (Dorothea Lange, Courtesy of National Archives)

“She never learned how to write her name,” Watanabe recalls. “When she became a naturalized citizen, she didn’t do it, she signed an ‘X,’ but she wrote her name on that suitcase… and then it’s got that number after it.”

Watanabe says it’s important to collect this heritage before it disappears.

“My dad, who was a friendly sort of person, if he saw someone he thought was Japanese American and about his age, he’d … strike up a conversation,” she recalls. “Their whole conversation was about, ‘Which camp were you in?’ and then they would figure out ‘Well, did you know so-and-so? What kind of things did you do?’”

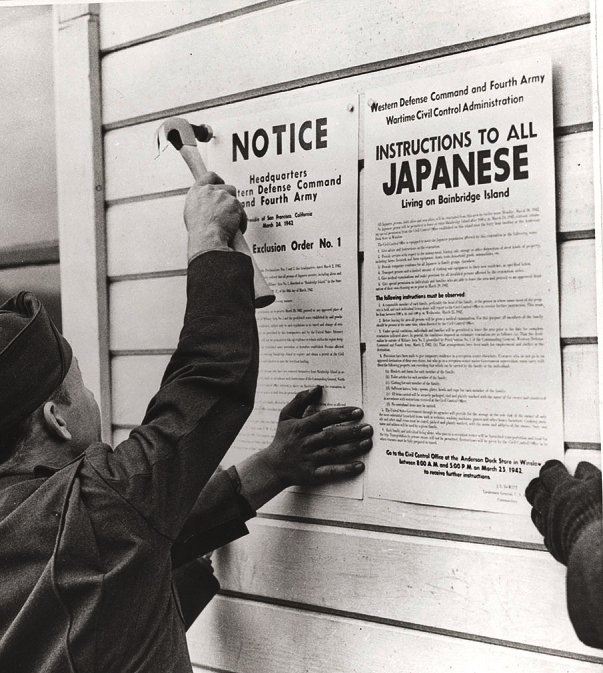

Posting the Exclusion Order, Bainbridge Island, Washington, 1942 )Courtesy Museum of History and Industry, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection)

“For their generation, they knew,” Watanabe says. For those they leave behind, though, the weight of a legacy, personal and global, can be daunting.

“The older people are dying, and all of a sudden the younger ones here were forced with the decision of what to do with,” these objects she says. “The Smithsonian turns out to be a very good repository.”

Jones says Noriko Sanefuji, a museum specialist in the American History Museum’s Armed Forces History Division, has been invaluable in soliciting and collecting many of the objects on view in “Righting a Wrong.”

“[Watanabe] donated this suitcase because Noriko asked her,” Jones says. “I’ve known Barbara for years and I never bothered to ask. … Noriko has been fantastic at being that person who can go and talk to people in the community and get those stories.”

Nakano family and friends at Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming, around 1944 (Courtesy of Janice Nakano Faden)

Sometimes, Sanefuji says, the process can take years of friendship.

“A lot of them, they’re so humble that they think their artifacts are not worthy of the Smithsonian,” she says. “But it’s historically so valuable because we are the largest museum complex and we can reach millions and millions of people.”

Watanabe thinks the Smithsonian’s educational mission is important.

“A lot of these things … should really be saved in a place where someone can make use of them, particularly for educational purposes,” Watanabe says. “The Japanese American community is very adamant … that this sort of thing shouldn’t ever happen again.”

For example Seishi Oka, who was incarcerated at the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona, spoke with reporters during the exhibit’s February press preview about the impact such objects can have.

“For a lot of people, just thinking about it is not enough,” he says. “But actually seeing artifacts, actually seeing what happened to them is very important. … The Smithsonian has been a very integral and important part in all of this.”