By Maria Anderson

“Uprising Against ICE,” 2014 by Rosalia Torres-Weiner, Charlotte, N.C. North Carolina’s influx of unaccompanied minors from Central America and resultant deportations inspired this piece. An Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent in full SWAT gear reaches with handcuffs towards a humbly dressed, unarmed immigrant family. (Anacostia Community Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Pool)

Since the year 2000, there has been a rapid increase in the Latino population in the United States. Cities that have had a strong Latino presence for decades continue to grow, while areas with historically low Latino populations—the U.S. Southeast, for example—experienced exponential growth.

“Gateways/Portales,” a new exhibition at the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum in southeast Washington, D.C., takes a closer look at this growth in four cities–Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Md., and Charlotte and Raleigh, N.C.–using the community life elements of politics, education and food. It also incorporates a new and increasingly popular, gender-neutral term “Latinx” (Latin-x) to replace Latino and Latina in describing people of Latin American origin, heritage and descent in the U.S.

“I was fascinated by how these populations of Latinx newcomers retained their identities while incorporating into the existing community,” exhibition curator Ariana Curtis explains. “Latinxs are the largest non-white group in the U.S. and accounted for half of the nation’s growth between 2000 and 2012.”

“The boom of Latinx populations in Raleigh and Charlotte began even before 2000,” Curtis says. Between 1980 and 2000, Latinx populations in these cities rose by approximately 1,000 percent. The increase is due to a combination of U.S. births, migration from other states and immigration.

“Hispanics, the New Italians,” 2015, Rosalia Torres-Weiner, Charlotte, N.C. The Statue of Liberty is an iconic representation –both hopeful and painful −of arrival to the U.S. Currently Latin American immigration contributes to population growth in many gateway cities, creating urban change across the country.

Washington, D.C. became a Latinx gateway after World War II, with the population steadily growing in the 1950s and 1960s through today. Baltimore was a significant gateway city for European immigrants around the turn of the 20th century. Recently it has reemerged as a Latinx gateway, with a Latinx population growth of 150 percent between 1990 and 2012.

“These four cities are not what most of us think of as Latinx urban centers, like we do with Miami, New York and Los Angeles,” Curtis points out. “But it is undeniable that as these communities begin to change, so do the states and the country. It’s a shift that involves the entire nation.”

“Gateways/Portales” groups the cities into geographic pairs: Washington, D.C. and Baltimore are historically African American majority cities where the Latinx population grew while their general population declined. Raleigh and Charlotte experienced Latinx population hyper-growth (more than 300 percent), as well as a significant population growth in general.

“Geographic proximity means each pair of cities share resources and have some similarities, yet they still grow differently,” Curtis says. “It’s interesting to see how certain obstacles and opportunities to incorporating into community life overlap or are unique to each city.”

The exhibition is divided thematically instead of by city to convey the similarities and differences across city lines. It focuses specifically on social justice and civil rights, making home and constructing communities, and festival as community empowerment.

“In the first section we take a look at issues of social justice and civil unrest,” Curtis explains. “We talk about the Latinx community clashing with law enforcement, like they did during D.C.’s 1991 Mt. Pleasant riots and Baltimore’s 2015 riots. We also examine the rise of Latinxs organizations for worker’s rights, especially farmworkers.” (North Carolina is sixth in the country in migrant farmworker population. The majority are native Spanish speakers.)

“This section also highlights how other communities have helped,” Curtis adds. “For example, African American businesses and individuals helped launch the Latino Cooperativa Credit Union near Raleigh, which has been promoting financial education and access for the growing Latinx population.”

The exhibit’s second section focuses on how Latinxs have made their new communities more inclusive, through political representation, local Spanish-language media and food.

“Access to food from their countries of origin is important for Latinxs in these communities,” Curtis observes. “Before there was a Hispanic food aisle in mainstream grocery stores, Latinxs shopped in small community stores that carried the brand names they recognized.”

“Saturday morning at a Dominican salon in Baltimore,” photo by Alejandro Orengo, 2016. (Anacostia Community Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Pool)

“Food as a point of access to communities has redefined local cuisine and led to a fusion of flavors, like Southern-Latino,” Curtis says. Objects on exhibit include a biscuit cutter and a tortilla press that belonged to cookbook writer Sandra Gutiérrez, from the Raleigh area. Her first cookbook, The New Southern-Latino Table: Recipes That Bring Together the Bold and Beloved Flavors of Latin America and the American South (2011), is also on display.

Latinx population growth also led to the appearance of local Latinx media. “Being able to connect to your immediate community is different from getting national news in Spanish,” Curtis explains. Latinx media outlets provide information relevant to the local Latinx community. Among the first Latinx newspapers were El Pregonero (1977) in Washington, D.C., La Voz de Carolina (1994), which was distributed throughout the Carolinas, and Latin Opinion (2004) in Baltimore.

The exhibit’s third section showcases the gathering and educational power of community festivals.

“More than offering a fun time, festivals offer undeniable proof of a Latinx presence in the community,” Curtis observes. “They are a place to meet people of similar backgrounds who are going through similar circumstances.”

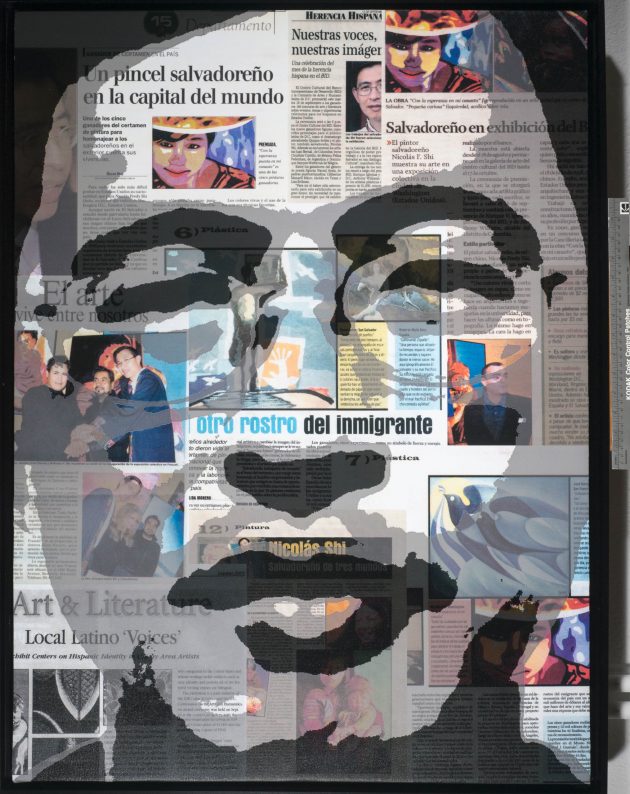

“El Otro Rostro del Immigrante (the Other Face of an Immigrant),” 2010 by Nicolás Shi, Washington, D.C. This self-portrait is a collage of newspaper headlines and articles celebrating the artist’s accomplishments. This positive face of immigration exists in contrast to pervasive negative immigrant stereotypes. (Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center)

Latinx festivals highlighted in the exhibition began out of activism, in smaller locations, and grew to become city-center, multi-block, all-day celebrations. They are: Fiesta DC, established in Washington, D.C. in 1970; Latino Fest, established in Baltimore in 1980; La Fiesta del Pueblo, established in the Raleigh area in 1994; and Hola Charlotte, established in Charlotte in 2012.

“Gateways/Portales” features more than 80 objects, including artwork recently acquired by the museum, two pieces commissioned specifically for the exhibition. “I’m an anthropologist first,” Curtis says. “It was important for me to craft the story first and find art that would enhance it. Most of the artwork, which is interspersed throughout the exhibition, offers a social commentary that helps tell the story.”

“Madre Protectora,” 2015 by Rosalia Torres-Weiner, Charlotte, N.C. This re-imagining of la virgin de Guadalupe as a millennial with an AK-47 shows that faith can be as strong as the challenges we face. (Anacostia Community Museumpurchase through the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Pool)

“Gateways/Portales, ” on exhibit through Aug. 6, 2017, is fully bilingual and is one of three bilingual exhibitions currently on view at the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum. The other exhibitions are “From the Regenia Perry Collection: The Backyard of Derek Webster’s Imagination” and “Bridging the Americas: Community and Belonging from Panama to Washington, D.C.”