by Maria Anderson

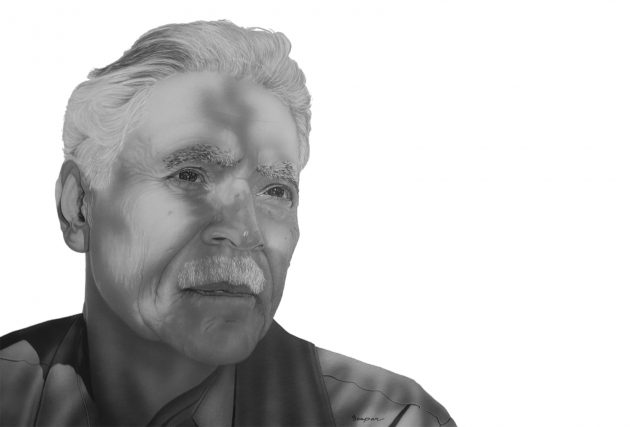

New Mexican author Rudolfo Anaya, recent recipient of the National Endowment for the Humanities National Humanities Medal and author of the nationally best-selling novel “Bless Me, Ultima.” This 2016 portrait by Gaspar Enriquez was commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery.

The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery tells America’s history through portraiture. It holds more than 24 thousand portraits of people who have made contributions of national impact in many fields, including politics, science, entertainment and the arts.

The museum has acquired most of its portraits through collector donations or from the artists and sitters directly. Sometimes when a portrait is not available—either no portraits exist or they’re in private collections or other museums—the Portrait Gallery commissions one. This was the case when the museum recently commissioned a portrait of a Latino individual by a Latino artist for the first time.

“As the Portrait Gallery’s curator of Latino art and history, I have an ongoing list of Latinos and Latinas who have made contributions to the nation that I would like to see represented in the collection,” Taína Caragol says. “One of them was New Mexican author Rudolfo Anaya, a recent recipient of the National Endowment for the Humanities National Humanities Medal. I wanted to exhibit his portrait to bring visibility to him and his work.”

Anaya’s nationally best-selling novel, Bless Me, Ultima, was published in 1972 during the Chicano Movement. It tells the story of a young boy struggling with conflicting expectations and values in post-World War II New Mexico. Anaya’s writing is rich with the culture and landscape of the Southwest, from its Spanish and Mexican roots to arid deserts.

“Since there wasn’t a suitable portrait of Anaya in existence that the museum could acquire, I thought perhaps we could commission one,” Caragol says.

John from De Puro Corazon series by Gaspar Enriquez, 2013, Collection of the artist. (Image copywrite Gaspar Enriquez)

Artist Gaspar Enriquez was chosen to create one on commission. Based near El Paso, Enriquez is a well-known portrait artist who specializes in depicting the soul of his subjects in his paintings. The very essence of where his subjects are from–their heritage and past experiences–is reflected in Enriquez’s portraits.

“The museum didn’t have a work by Gaspar so I jumped at the opportunity to add him to our collection. As a curator and art historian I was pleased to showcase an artist who has made great contributions to the field of portraiture and to his community,” Caragol said.

Another reason for choosing Enriquez to do Anaya’s portrait was the fact they had previously worked together. Enriquez had illustrated Anaya’s book Elegy on the Death of César Chávez.

“This commission also was significant because it represents a piece of a larger Latino experience in the U.S.,” Caragol explains. “Museums often represent Latino art from the two coasts, primarily California and New York, but there’s a lot happening in other parts of the country. The opportunity to have Anaya and Enriquez represented in our museum was a way of acknowledging the Latino art production from the middle of the country, the Southwest.”

Enriquez was born and raised in El Paso’s Segundo Barrio, a neighborhood that served as a port of entry from Mexico to the United States for many years. He moved to California when he turned 18 to work as a machinist, while attending art classes at East L.A. Junior College. He eventually returned to El Paso and earned a bachelor’s degree in art from the University of Texas at El Paso and a master’s in metals from New Mexico State University in 1985. After graduating, he decided to become an art teacher. He taught at El Paso’s Bowie High School for 34 years.

“I started teaching in the same neighborhood where I grew up and saw the same problems that I faced as a teen, like gangs, drugs and kids dropping out of school,” Enriquez says. “I wanted to capture what they were going through, as a metaphor of my life through theirs.”

Enriquez developed a unique portraiture technique that depicts the subject with very little context, usually against white backgrounds. He also airbrushes his portraits, a process that can take months to complete.

“I started out painting with a regular brush but since I was doing portraits I wanted a better way to subtly paint shadows across a face and the airbrush allowed me to do that,” Enriquez says. “At the time I didn’t know how difficult it was going to be. But I practiced and practiced until I got the hang of it.”

You have to look very closely at his portraits to figure out what material Enriquez uses. He usually makes a drawing of his subject first and takes a few photographs. “From the first drawing I make another drawing that I cut up to make stencils. I airbrush the paint through the stencils and add some detail with a brush. That’s how I do it,” Enriquez explains.

The shadows that he airbrushes across his subjects’ faces serve as context clues.

“I like to work shadows into portraits. It makes the portrait more revealing yet also mysterious as the viewer wonders what the shadow is from. In Rudolfo’s case, I took him all around his house to find the right shadow for him. The shadow on his face is from a big pear tree in his front yard,” Enriquez says.

Along with Anaya’s portrait, Enriquez has another work on view at the National Portrait Gallery. He was one of the winners of Portrait Gallery’s Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition, which invited artists from across the country to submit their best works in the art of portrayal. To view Enriquez’s winning work, visit “The Outwin 2016: American Portraiture Today”.