By Maria Anderson

Baseball gloves and ball donated by family of Leopoldo Martinez. Martinez played for teams in Mexico, Texas, and in the Los Angeles area. He played in Cartagena, Colombia and Managua, Nicaragua for the Mexican National team. (Courtesy of the National Museum of American History, photo by Jaclyn Nash)

Few things are more American than baseball: playing catch during the summer, going to the ballpark, rooting for your team in the World Series. Stories around baseball help tell the story of the country itself, through the communities that surround the sport.

Many Latino communities across the U.S. have been participating in baseball for decades. Their stories are at the center of a collecting initiative at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History: “Latinos and Baseball: In the Barrios and the Big Leagues.” Smithsonian Insider asked museum curator Margaret Salazar-Porzio about this project and the importance of weaving these stories into the fabric of U.S. history.

Q: What spurred this collecting initiative?

Salazar-Porzio: When I started working at the National Museum of American History in 2013, I knew that I wanted to tell stories about Latino communities through different lenses. The museum had many great objects from Latinos in major league baseball, including Roberto Clemente’s Pittsburg Pirates jersey, but no objects representing community baseball leagues that reflect everyday local stories. Baseball for many Latinas/Latinos is so much more than only a major league story.

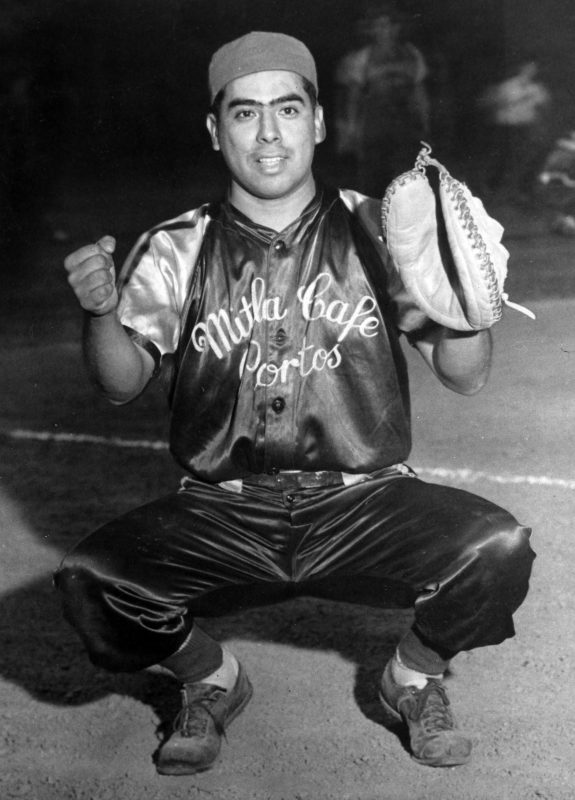

Many local Mexican-owned businesses funded baseball clubs. Business sponsors provided funds for uniforms, field maintenance and equipment. The Mitla Café, founded in 1937 and still in operation today, sponsored a community baseball team in San Bernardino’s west side that went on to win three consecutive city-league championships from 1947-1949. Ralph Botello poses in his Mitla Café Portos uniform in 1949. (Courtesy of the Latino Baseball History Archive, California State University of San Bernardino.)

Community leagues are prevalent in the Los Angeles area, where I grew up. Several scholars at the National Museum of American History and other organizations had started telling this broad story. Scholars such as Adrian Burgos, who focused on how Latinos broke the color barrier long before Jackie Robinson, and Jose Alamillo, who told the history of how Latinas/Latinos became community organizers around the baseball diamond.

I realized that baseball provides an incredibly rich entry point for telling the stories of Latina/Latino communities. That realization inspired this project. So we are collecting stories about these community leagues, not just in California but throughout the country. Most of these stories have nothing to do with the major leagues, but they’re important because they speak to Latina/Latino experiences in the U.S.

Q: How is the Latino community involved in these baseball leagues?

Salazar-Porzio: Community baseball leagues attract everyone. From the players themselves to their families, fans of the sport and even the lady selling churros. Many people are involved in the experience, which is what makes it so unique. It’s not a story about making it big—although some players who start in community leagues do make it to minor and major league baseball. It is rather a story centered around the community itself, about people building relationships with each other and their surroundings.

The Latino community baseball fan base is broad. The players’ families and the community at large gather to cheer at the games but it goes beyond that. Community leagues have a lot of dimensions. They attract the interest of local entrepreneurs. They make interesting community connections. Restaurants, businesses and even well-known brands, like Goya, sponsor teams.

This community involvement is more evident in little league baseball. It attracts community organizations who want to contribute to an activity that they see having a positive impact on their youth. People give back to their community by volunteering and making donations to little leagues.

Jersey belonging to Roberto Clemente, a Puerto Rican baseball player who spent 18 Major League Baseball (MLB) seasons as a right fielder for the Pittsburgh Pirates. He was the first Latin American and Caribbean player inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, in 1973. (Courtesy of the National Museum of American History)

Q: What types of objects are you looking for?

Salazar-Porzio: Collecting objects for a museum takes time. It’s a process that requires us to make connections and follow-up with individuals and organizations interested in sharing their stories. We kicked off our collecting initiative in February of this year in San Bernardino, Calif. The event brought together community members, baseball enthusiasts and scholars from across the country to discuss the role of baseball in community-building among Latinos.

Since then we have had five more collecting events, two in Los Angeles; and one each in Kansas City, Missouri; Syracuse, New York; and Alamosa, Colorado.

This is where we begin to see what objects we are interested in collecting and start making connections with people willing to donate them. We also get a sense of their stories, which are what bring the objects to life, and follow up with them to get oral histories about community baseball.

Besides the more obvious sports paraphernalia, like the jerseys, baseball bats and autographed balls, we are focusing on collecting objects that relate directly to the community. For example, a pretzel and churro cart, posters and signs made by the players’ families, or trophies awarded to playoff winners.

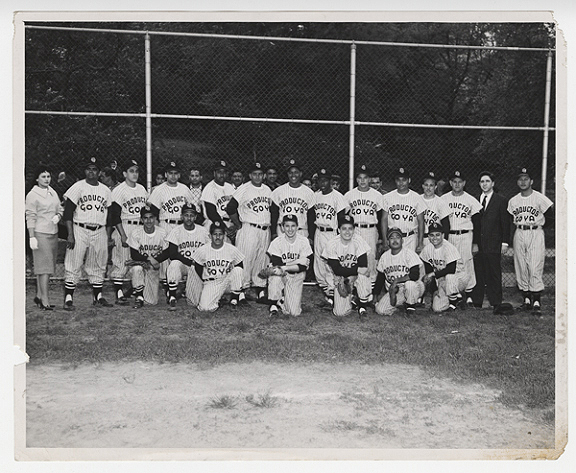

Goya was one of many companies that sponsored local teams of Latina and Latino players. (Courtesy of the National Museum of American History)

Q: What are some of the stories you’ve gathered so far?

Salazar-Porzio: In Los Angeles we are preserving some very exciting family stories through scrapbooks, a well-used glove, a hat, a ball and other memorabilia. From Kansas City we received a donation of a 1950s letterman jacket with an Azteca champion patch and a 1970s Azteca uniform, among other items.

We recently teamed up with Priscilla Leiva from California State University, Los Angeles for an event focusing on preserving the community history of Chavez Ravine in Los Angeles. This was a primarily Latino, working-class neighborhood that was bulldozed to make room for Dodgers stadium in 1958. At the event, community members came forward with their heirlooms for preservation, including pictures of the Elysian Park community baseball team. This baseball team is particularly interesting because all the players were from the neighborhoods that made up Chavez Ravine.

These people were displaced to build a baseball stadium, yet they were also baseball fans who loved the game and played it in their free time. Documenting their experiences adds a nuance to the story of Latinos and baseball because it uniquely links the events that changed their lives forever to something they truly enjoyed.

Another story that I’m interested in is the role of community baseball leagues as a platform for workers’ rights. A large segment of the mid-20th century Latino population in California and across the Southwest were agricultural workers who sought fair labor practices. Baseball served as a forum for them to connect and discuss their plight. With our partners Gabe and Jody Lopez, we have been able to identify a range of artifacts from the sugar beet fields in Colorado and Wyoming, including a short-handled hoe, that would help tell this story in the context of an exhibition.

Q: Why is it important to collect these stories?

Salazar-Porzio: To me, this collecting initiative is about preserving memories. Much of what we have heard comes from the early to mid-20th century, so it’s important to collect these stories now before the people who know them pass on. We want to preserve the story of Latinos in the U.S. through the lens of a beloved American sport, so that future generations can learn more about Latinos…in the barrios and the big leagues.

Objects and stories that become part of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History collections are national treasures forever preserved for the American public. When donors share their oral histories and artifacts, they help provide clarity, insight and first-hand knowledge to enrich Smithsonian collections. These stories become part of our nation’s heritage, and their words, shared insights, artifacts and pictures will live on long after we are gone.