By John Barrat

This menacing ambush predator, a mite from the family Cheyletidae, lurks on a leaftop waiting for a tasty victim to pass by. (Photo courtesy Electron & Confocal Microscopy Unit USDA-ARS)

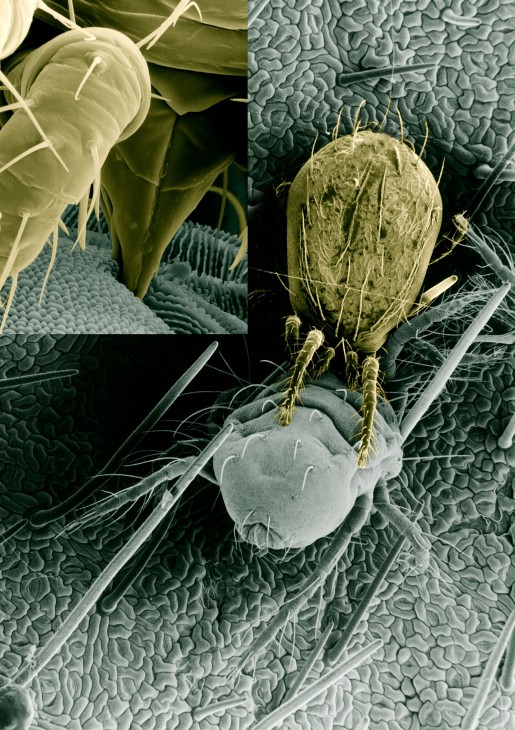

Lurking on leaves in the tropical forests of Brazil microscopic mites in the family Cheyletidae are ambush predators. They wait quietly until another mite crawls by and then they seize it with hook-like claws and sink their piercing, cutting mouthparts into the victim’s wriggling body. A second predatory mite family, the Phytoseiidae, are fast runners that snag their victims “like a terrier catching a rat,” explains mite expert Ronald Ochoa, an adjunct scientist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and an entomologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Evidence of these voracious attackers can be seen in the defensive body adaptations of two newly named mites, Excelsotarsonemus tupi and E. caravelis, with whom the Cheyletidae and Phytoseiidae are closely associated. Compact and aerodynamically shaped, E. tupi and E. caravelis are gentle fungi feeders that can retract their entire mouth and feeding parts (called gnathosoma) into their tough shells (called the prodorsum) like turtles. “With their strong bodies these little guys have a very good chance to survive an attack from predatory mites which are twice their size,” Ochoa says.

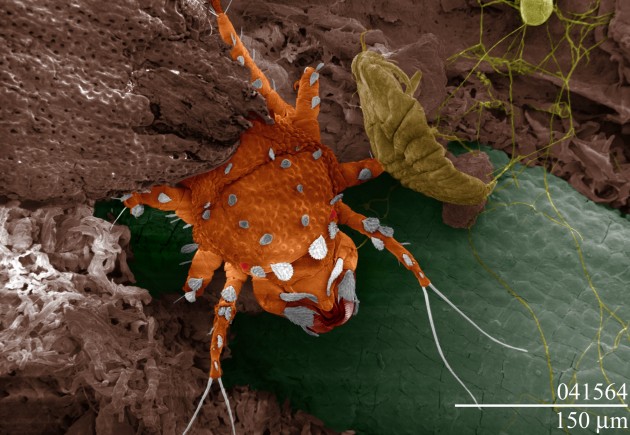

This scanning electron microscope image shows the new Brazilian mite “Excelsotarsonemus caravelis,” named after the sailboats, or caravels, used by Portuguese explorers who arrived in Brazil at the end of the 15th century. It’s front end is on the right. Setae on its back end help it ride breezes from tree to tree in the rain forest canopy. Its compact body and wax coating help it survive attacks from predatory mites. (Photo Electron & Confocal Microscopy Unit USDA-ARS)

An arrangement of feather-like sails—highly modified hairs called setae—on both mites’ bodies also help defend these microscopic creatures from predators, and allow them to glide around the tropical forest canopy on the faintest breeze. E. caravelis, in fact, is named after the sailboats, or caravels, used by the Portuguese explorers who arrived in Brazil at the end of the 15th century. E. tupi, is named in honor of the Tupi people of Brazil, an indigenous tribe that once inhabited most of Brazil’s coastline.

Both mites, collected near the campus of Santa Cruz State University in Bahia State, Brazil, were described and named in a recent issue of the journal ZooKeys. Ochoa is a co-author of the paper along with Jose Rezende and Antonio Lofego of Sao Paulo State University in Brazil, and Gary Bauchan of the USDA’s Electron and Confocal Microscopy Unit.

A third defensive adaptation of both newly named mites is that glands on their bodies continually keep their shells coated in a thick layer of wax. “Like humans who drop skin cells and grow new skin these mites grow new wax and the old wax just drops off,” Ochoa says. “When they drop the wax all the fungi and bacteria attached to their body drops with it. It’s a very fantastic and natural way of cleaning and protecting yourself. Think of having a car that can wax itself.”

This mite, recently discovered in a coca plantation in Brazil, was just named “Excelsotarsonemus tupi” in honor of the Tupi people of Brazil, an indigenous tribe that once inhabited most of Brazil’s coastline. Feather-like setae on its body allow it to ride breezes from tree to tree in the forest canopy. (Photo courtesy Chris Pooley / Electron & Confocal Microscopy Unit USDA-ARS)

The wet, high-humidity environment of the rain forest makes constant cleaning of fungi and bacteria a necessity for these creatures. Dropping parts of their wax shell, “is an amazingly effective way that fungi and bacteria get dispersed around the forest,” Ochoa adds. Their wax coating also helps the mites retain moisture.

New mite species are everywhere, Ochoa concludes. “When I am in the cloud rain forests of Costa Rica, in the middle of this mist, I cannot stop thinking about how many mites are floating all around me and I just cannot see them.”

Ochoa and Rezende are now working on a new paper describing and naming 11 new species of mites from the rain forest of Costa Rica. “We are just scratching the surface of this world,” they say.