Birds do it. Bees do it. And in a laboratory in northern California, scientists using bumblebees recently figured out the best way to measure it. For biologists who study flight, knowing the maximum vertical lifting strength of a species can lead to a better understanding of how an animal escapes predators, pursues or flees potential mates, and transports its food. Yet calculating the vertical lifting capacity of a small bird or insect is no simple matter.

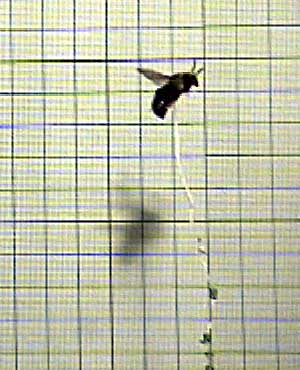

Photo right: A bumbleebee lifts a string of weights in an experiment in the Animal Flight Laboratory at the University of California. The grid behind the bee enables researchers to measure exactly how high the bee ascends from the ground. (Photo courtesy Robert Buchwald)

Recently, scientists Robert Buchwald and Robert Dudley of the Animal Flight Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley (Dudley is also a Research Associate at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama), tested the accuracy of two different methods of calculating an insect’s load lifting ability on bumblebees (Bombus impatiens). They found that bumblebees can lift (in addition to their own bodies), on average, 53 percent of their body weight. Yet one of the methods they tested underestimated the bees’ strength by 18 percent.

Scientists began using the cumulative method of measuring lift in 1987. It involves attaching one tiny weight to the abdomen of an insect with a string. Each time the insect flies and raises the weight into the air, additional weight is added until the insect can no longer raise it from the ground. The weight of the final load lifted and the weight of the maximum load not lifted are averaged together and added to the body weight of the insect to determine its maximum vertical lift.

This slow-motion video shows a bumblebee lifting a string of weights in the Animal Flight Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley. The left side of the screen shows the testing chamber from above, looking down upon the experiment. The right side is a lateral view of the chamber as seen in a mirror set at a 45-degree angle. The mirror lets the scientists see how high the bee is flying. Slowing down the audio recording of this experiment enables the researchers to calculate the wingbeat frequency of a bee during periods of maximum vertical lift. (Video courtesy Robert Buchwald)

A second method established in 2004, the asymptotic method, involves attaching a long string of tiny, evenly spaced weights to a bee’s petiole or midsection. As the bee rises it pulls the string of beads up with it until the chain becomes too heavy to lift further, at which point the bee hovers. The weight of the beads lifted from the ground, the weight of the string and the bee’s body weight are added together to determine the bee’s vertical lifting strength. Data from this method, on average, indicated bumblebees had an 18 percent higher vertical lifting ability than data gathered using the cumulative method.

Why is knowing the vertical lifting strength of a bumblebee important to biologists?

“Escape and chasing performance for flying animals can profoundly influence survival and, in some cases, mating success,” Dudley says. “Identification of the physiological and biomechanical limits to flight performance can indicate more general features of the behavior, ecology, and evolution of flying animals.”

Orchid bees tested in Panama lifted about 100 percent of their body weight using the same [asymptotic] method, Dudley explains, so bumblebees are on the low side of vertical lifting strength among bees. “They aren’t really high-performance fliers, rather better at transporting nectar and pollen loads—typically less than 50 percent of their body weight—back to the nest at regular intervals.”

A paper by Buchwald and Dudley describing these results was published in a recent issue of the Journal of Experimental Biology. —John Barrat