By John Barrat

A Laysan albatross estimated to be at least 63-years-old and chick Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge (John Klavitter/U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

(Study is one of dozens to be presented by bird scientists this week at the

2016 North American Ornithological Conference in Washington, D.C.)

To catch tuna in the Pacific today, many commercial fishing ships set a series of long lines through the water—lines that are bristling with hundreds and even thousands of baited hooks. While a chunk of squid may be irresistible to a tuna, many seabirds also chase and swallow these fishing baits.

Albatrosses, including Hawaii’s black-footed and Laysan albatrosses, feed at the ocean’s surface. “Bait on a hook is tempting. It looks like easy prey before the long line sinks into the sea,” explains Autumn-Lynn Harrison, a marine ecologist at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. “But, going after the bait means an albatross can also get caught on the hook, become injured, or even drown,” Harrison says.

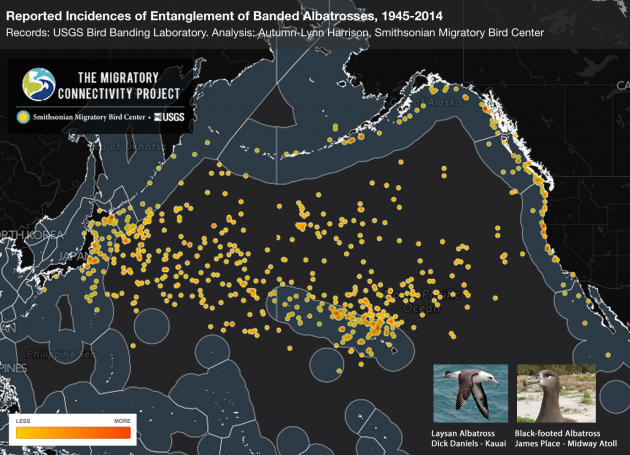

Created from a database maintained by the United States Geological Survey, this map plots the location of fishing-gear entanglements of all banded albatrosses in the Pacific from 1945-2014. (Image courtesy Autumn-Lynn Harrison)

Albatrosses are one of the most threatened groups of birds globally and information about their interactions with fisheries is important. When fishing vessels pull in the line to release or salvage the bird, they are encouraged to also look for a band on its leg. Metal bands are placed on albatross chicks in the nest, or on breeding adults. A band can identify the specific colony where it was born and its age, or for birds banded as breeding adults, where it bred.

If a hooked albatross has a band on its leg, it is hoped the band information and the circumstances of how it was obtained is reported to the United States Geological Survey, which maintains the North American Bird Banding Database. Database records go back to the 1920s, when major fishing operations hadn’t yet left the coast to spread throughout the open ocean. Many original band-return records of albatrosses banded by Smithsonian biologists in the 1960s can even be found in our own records at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

Two of thousands of return cards maintained in the Smithsonian’s Pacific Ocean Biology Survey Project. These two cards document the entanglement of a banded black-footed albatross on the California coast and a banded Laysan albatross in Japan. (Image courtesy Autumn-Lynn Harrison).

This week, Harrison will speak on large-scale patterns of bird entanglement in fishing gear in North and South America and the Pacific at the 2016 North American Ornithological Conference in Washington, D.C. One of the largest ornithological conferences ever held, lectures by dozens of world experts, workshops, roundtable discussions and interactive sessions and symposia on a vast array of bird-related topics will be featured. Held every four years, this year’s conference runs from Tuesday, Aug. 16 to Saturday, Aug. 20 and is being hosted by the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center.

In addition to albatrosses, entanglement of North American banded birds by fishing operations, including recreational fishing, also is reported in large numbers for royal terns, double-crested cormorants, and brown and white pelicans. Globally, entanglement by fishing is a primary reason “all of the 22 species of albatross is listed in someway on the International Union for Conservation Nature Red List of Endangered Species,” Harrison continues.

This interactive map was created from data on all reported fishing-gear entanglements of birds of all species from 1920-2014. (Map courtesy Autumn-Lynn Harrison)

Harrison’s current research involves using the USGS Bird Banding database to investigate patterns that show if members of specific albatross colonies (many different colonies nest across the Hawaiian Islands) died more frequently as the by-catch of specific North Pacific fisheries.

Albatross by-catch by the fishing industry is a well-studied phenomenon, yet “how different colonies might be impacted differently because of their migration patterns is just starting to come to light,” Harrison says. The traditional migration route of a specific colony may place its members in harm’s way at specific times of operation—right in the seasonal path of a commercial fishery. Another colony in a different area may not face this threat.

“I am trying to learn what 100 years of banding data can tell us about which colonies were caught in which fisheries and how this might have changed through time. Birds that breed on Midway Island in the northwestern Hawaiian Islands [west], for example, may have a higher likelihood of being caught by an Asian fishing fleet versus birds that breed on Kauai or Oahu Islands in the main Hawaiian Islands [east] that are caught more frequently in Hawaiian long-line fleets.”

Laysan (foreground) and black-footed albatrosses in flight at Southeast Eastern Island, Midway Atoll, Hawaii, April 2015. (Flickr photo by Forest and Kim Starr)

Albatross death by long-line fishing is “changing over time,” Harrison observes. “Fishing fleets have become more aware about the impacts of their operations on seabirds, and have gotten smarter about ways to try to get albatrosses away from their fishing vessels. A lot of this work is really improving the ways fisheries are able to avoid bird by-catch.”

Second to commercial fishing as a marine bird hazard, Harrison says, are two other human-introduced threats: floating plastics that albatrosses feed to their chicks, and climate change. “Many marine birds nest on low-lying islands that are likely not to be there in the future,” due to rising sea levels.