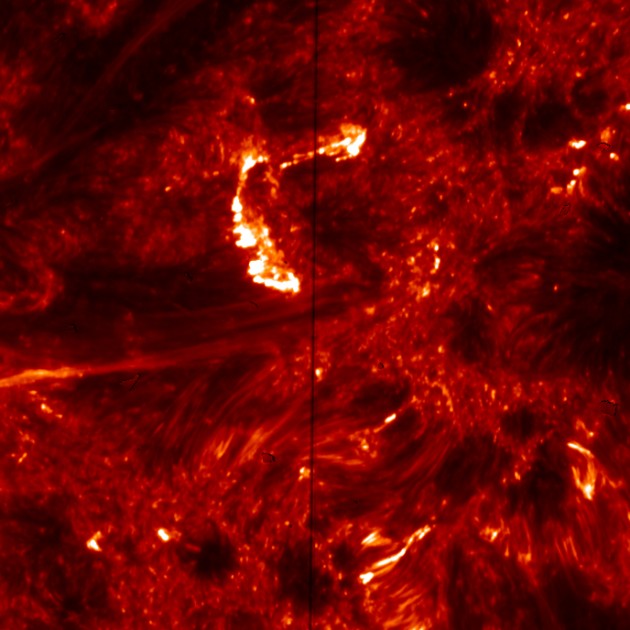

This image from the Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) shows emission from hot plasma in the Sun’s transition region-the atmospheric layer between the surface and the outer corona. The bright, C-shaped feature at upper center shows brightening in the footprints of hot coronal loops, which is created by high-energy electrons accelerated by nanoflares. The vertical dark line corresponds to the slit of the spectrograph. The image is color-coded to show light at a wavelength of 1,400 Angstroms. The size of each pixel corresponds to about 120 km (75 miles) on the Sun.

(NASA/IRIS image)

Why is the Sun’s million-degree corona, or outermost atmosphere, so much hotter than the Sun’s surface? This question has baffled astronomers for decades. Today, a team led by Paola Testa of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) is presenting new clues to the mystery of coronal heating using observations from the recently launched Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS). The team finds that miniature solar flares called “nanoflares” – and the speedy electrons they produce – might partly be the source of that heat, at least in some of the hottest parts of the Sun’s corona.

A solar flare occurs when a patch of the Sun brightens dramatically at all wavelengths of light. During flares, solar plasma is heated to tens of millions of degrees in a matter of seconds or minutes. Flares also can accelerate electrons (and protons) from the solar plasma to a large fraction of the speed of light. These high-energy electrons can have a significant impact when they reach Earth, causing spectacular aurorae but also disrupting communications, affecting GPS signals, and damaging power grids.

Those speedy electrons also can be generated by scaled-down versions of flares called nanoflares, which are about a billion times less energetic than regular solar flares. “These nanoflares, as well as the energetic particles possibly associated with them, are difficult to study because we can’t observe them directly,” says Testa.

This image from the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly on board NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory was taken simultaneously with the IRIS observations. It shows emission from hot coronal loops in a solar active region. IRIS observed brightenings occurring at the footpoints of these hot loops. The image is color-coded to show light at a wavelength of 94 Angstroms. The size of each pixel corresponds to about 430 km (270 miles) on the Sun.

(NASA/SDO image)

Testa and her colleagues have found that IRIS provides a new way to observe the telltale signs of nanoflares by looking at the footpoints of coronal loops. As the name suggests, coronal loops are loops of hot plasma that extend from the Sun’s surface out into the corona and glow brightly in ultraviolet and X-rays.

IRIS does not observe the hottest coronal plasma in these loops, which can reach temperatures of several million degrees. Instead, it detects the ultraviolet emission from the cooler plasma (~18,000 to 180,000 degrees Fahrenheit) at their footpoints. Even if IRIS can’t observe the coronal heating events directly, it reveals the traces of those events when they show up as short-lived, small-scale brightenings at the footpoints of the loops.

The team inferred the presence of high-energy electrons using IRIS high-resolution ultraviolet imaging and spectroscopic observations of those footpoint brightenings. Using computer simulations, they modeled the response of the plasma confined in loops to the energy transported by energetic electrons. The simulations revealed that energy likely was deposited by electrons traveling at about 20 percent of the speed of light.

The high spatial, temporal, and spectral resolution of IRIS was crucial to the discovery. IRIS can resolve solar features only 150 miles in size, has a temporal resolution of a few seconds, and has a spectral resolution capable of measuring plasma flows of a few miles per second.

Finding high-energy electrons that aren’t associated with large flares suggests that the solar corona is, at least partly, heated by nanoflares. The new observations, combined with computer modeling, also help astronomers to understand how electrons are accelerated to such high speeds and energies – a process that plays a major role in a wide range of astrophysical phenomena from cosmic rays to supernova remnants. These findings also indicate that nanoflares are powerful, natural particle accelerators despite having energies about a billion times lower than large solar flares.

“As usual for science, this work opens up an entirely new set of questions. For example, how frequent are nanoflares? How common are energetic particles in the non-flaring corona? How different are the physical processes at work in these nanoflares compared to larger flares?” says Testa.

The paper reporting this research is part of a special issue of the journal Science focusing on IRIS discoveries.