By John Barrat

Baleen hangs from the palate of this gray whale swimming in the Pacific near Baja, California. (Flickr photo by Ryan Harvey)

A bizarre change occurs in the mouth of a humpback whale during its development in the womb. Several dozen tooth buds sprout in a row on both sides of its lower jaw then vanish without a trace.

Adult humpbacks have no teeth. They eat by gulping massive quantities of water that they push out through a curtain of baleen that grows like a broom from their palate. The baleen filters out small fish and plankton that the whale then swallows. Humpback, right, blue, gray and rorqual whales are a few living baleen feeders, also known as mysticetes.

Teeth that sprout then vanish in the mouths of humpback fetuses are an ancient vestige from a time when mysticetes were toothy, fearsome predators. Llanocetus denticrenatus, for example, lived about 32 million years ago in the Late Eocene epoch, was a good swimmer and had a mouth full of large, pointy teeth perfect for catching, holding and dismembering prey.

How and when baleen first appeared is one of the great mysteries of whale evolution–a detective story paleobiologists would love to solve. But scientists attempting to unravel baleen’s origins have for years been confronted with a broad and imposing array of research spanning centuries that is filled with difficult-to-follow leads and clues. From a detective’s perspective, the case file on baleen required much-needed maintenance to organize evidence and reframe some fundamental questions.

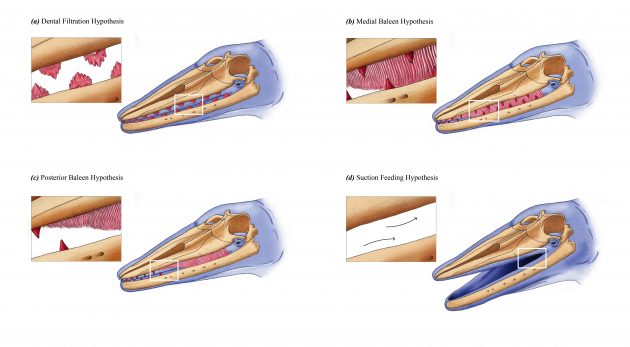

Four hypothetical transitional filter feeding stages in mysticetes, with oblique lateral views of a generalized stem mysticete. These hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, nor explicitly stepwise. (Artwork courtesy Alex Boersma www.alexboserma.com. From Peredo et al. 2017.)

Enter Carlos Mauricio Peredo of George Mason University, with Nick Pyenson of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, and Alexandra Boersma of California State University Monterey Bay. In a new paper in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science, these three scientists have condensed, clarified and updated all current knowledge on baleen’s evolution—from studies more than a century old to modern DNA analysis. Their paper condenses existing research and establishes a framework of four different hypotheses by which baleen may have evolved in whales. Each hypothesis relies heavily on morphological evidence from whale fossils.

In their paper Peredo, Pyenson and Boersma propose baleen appeared in one of these four specific ways:

- Dental filtration: Filter feeding evolved first and the filtering was done through pointed teeth on the upper and lower jaws as the mouth was closed and water pushed out. Baleen evolved later to increase feeding efficiency.

- Medial baleen: Baleen evolved in a layer just inside the existing top teeth rows of whales, allowing them to alternate between filter feeding and catching prey with their teeth;

- Posterior baleen: Baleen first appeared on the palate far back in the mouth in two rows behind a short row of teeth in the front of the jaw, but in the same orientation on both sides of the palate as the teeth;

- Suction feeding: Whales become increasingly efficient at suction feeding, resulting in the loss of teeth independent from the evolution of baleen, which came later.

“A complete understanding of the origin of baleen must arise from interdisciplinary efforts and all available datasets,” the scientist argue in their paper. This mystery can be solved, only if we “ask questions in the right kind of framework.”

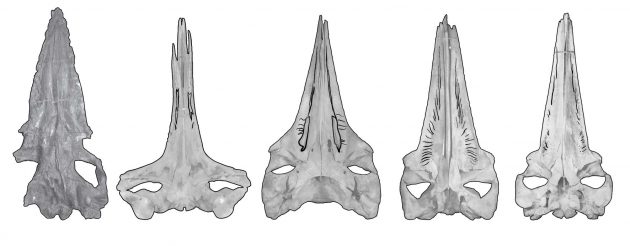

Skulls of fossil and living mysticetes, viewed from their palates. Black outlines indicate places where baleen grew. (Photo modified by Carlos Mauricio Peredo from Peredo et al. 2017.)

To achieve this, the authors diligently highlight the pros and cons to each hypothesis and outline ways in which each may be further tested through specific avenues of research. They propose that future investigations should quantify the different modes of feeding among all of these different early baleen whales, especially in the context of their evolutionary history.”

In their paper Peredo, Pyenson and Boersma take a key step forward by discouraging the idea that baleen’s appearance and tooth loss are somehow connected as part of a logical evolutionary progression. “Tooth loss and baleen evolution represent their own, distinct transitions,” Peredo, the paper’s lead author, says. “While the degree to which they are linked remains unknown, we argue they need to be tested as separate pathways.”

The how and why of whales losing their teeth and the how and why of whales developing baleen are not necessarily linked, Pyenson adds. “The way evolution works may appear linear from our standpoint like a ladder of progress leading to what we see today, but that’s not how it really works. Evolution works in happenstance in the context of a diversifying tree of life that is complex. So for baleen and tooth loss, it might have gone through all of the hypotheses we propose, just one of them, or in some sequence and not others, in some whales and not others. We just want to be explicit about the different ideas that could be out there.”

Humpback baleen. Baleen is a filtering structure used by mysticetes to remove small animals from mouthfuls of seawater. It grows in two rows from the palate and is made from keratin, the same substance as fingernails, feathers and hair. (Flickr photo by Randall Wade Grant)

While digging through the extant scientific literature on baleen, the scientists came to realize that lack of clarity was an issue, Peredo says. “By consolidating the literature into these four hypotheses, we aim to frame the question into a more clearly testable structure.”

In addition, Peredo continues, “we did something new. We went back to the old literature. We dug into literature that spans 200 years and eight different languages. The oldest dates to 1807. Much of the old literature we revived has been ignored because of inconsistent or outdated anatomical terminology.”

“More than anything, we’ve laid down some scaffolding and some blueprints for how the next stage of research can really progress in a fruitful way,” Peredo says.

“This kind of study is one you could almost only do here at the National Museum of Natural History,” Pyenson adds. While the literature is available online, many of the specimens on which the literature is based are in-house. “Ideas change all the time, new ideas and new questions arise but the facts of the specimens don’t. This is an important reason why museums exist.”

This specimen from the former “Life in the Ancient Seas” exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., is a cast of “Zygorhiza kochii.” This early whale from the Late Eocene had teeth and fed on fish before the rise of mysticetes and baleen filter feeding. (Photo by Don Hurlbert)

“The real contribution of this paper is that it clarifies what we think about how evolution works for this one particular phenomenon with baleen whales,” Pyenson adds. “We are encouraging a specific framework for talking about this and highlighting the kind of evidence we think is relevant.”

From their paper, it is clear that a great deal of research remains to solve the complex issue of the rise of baleen in whales. But with its publication Peredo, Pyenson and Boersma have made the odds much better that the mystery surrounding baleen will be correctly resolved sometime in the near future.